Meet Dr Love: the infallibly seductive, pioneering French gynaecologist

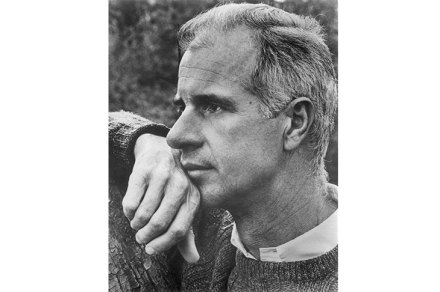

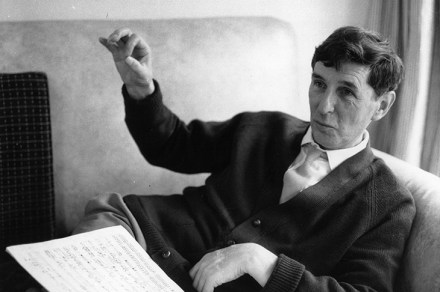

Do not google Samuel Jean Pozzi. If you want to enjoy Julian Barnes’s The Man in the Red Coat — and believe me, it’s teeming with delights — stay away from search engines and trust the author to tell the story in his own way. But just to get you started: Pozzi (1846–1918), the man John Singer Sargent painted, gloriously, in sumptuous red, was a Frenchman, a prominent, pioneering doctor in Belle Epoque Paris, and a charming, ubiquitous, infallibly seductive socialite. (‘Disgustingly handsome’ is how the Princess of Monaco described him.) He was Sarah Bernhardt’s doctor and also her lover; she called him ‘Docteur Dieu’. (His other nickname was ‘L’Amour