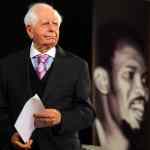

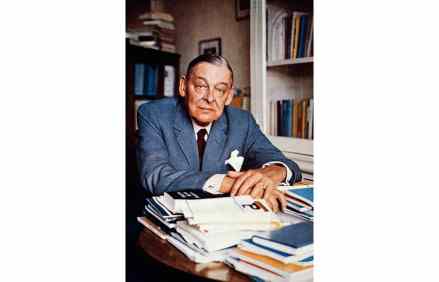

The visionary genius of Harold Wilson

‘Our generation owes an apology to the shades of Harold Wilson,’ the polling guru Peter Kellner once told me. Had Wilson not firmly resisted pressure from President Lyndon Johnson to send troops to Vietnam, Kellner and I were both old enough to have fought there. But in 1968 we loftily despised Wilson for twisting and turning to stay out of Vietnam and keep his party together. ‘What are the two worst things about Harold Wilson?’, we asked. ‘His face,’ we replied smugly. Britain has never quite forgiven Wilson for his cleverness. His reputation suffered a catastrophic decline in the immediate aftermath of his premiership. It was partially rescued by Ben