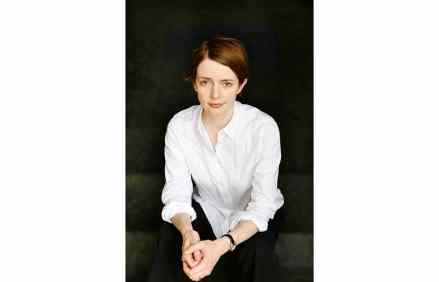

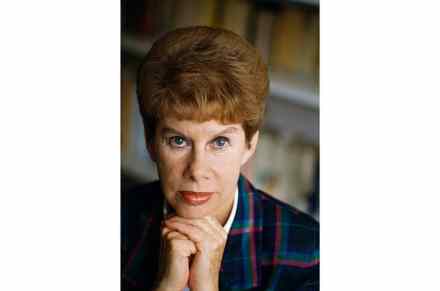

A flawed utopia: The Men, by Sandra Newman, reviewed

The problem for feminism is men. Not, specifically, in the sense that men are the source of women’s problems, although the statistics do tend to point in that direction. Feminism’s men problem is that, despite all this, women like men. Love men. One of the lessons of second-wave experiments in separatism is that the idealised man-free existence is always fighting against the gravity of affection. Sandra Newman’s novel The Men takes that quandary and does something clever with it. She imagines a world in which all the men and all the boys and all the trans women and all the male non-binaries and all the Y-chromosome-carrying foetuses are mysteriously spirited