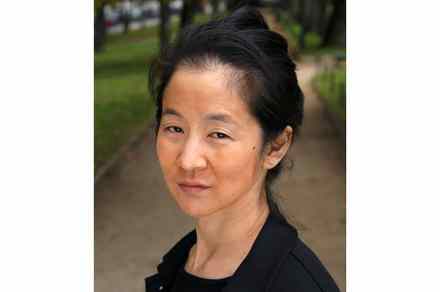

Zimbabwe’s politics satirised: Glory, by NoViolet Bulawayo, reviewed

NoViolet Bulawayo’s first novel We Need New Names, shortlisted for the Booker in 2013, was a charming, tender gem, suffused with the guileless hilarity of children and the shock of tragedy in Zimbabwe, the author’s birthplace. Her follow-up, Glory, features animals as characters. I was initially mystified. Who would try to match Orwell’s allegorical masterpiece Animal Farm? Art Spiegelman succeeded in Maus, his graphic novel about the Holocaust, but each species represented one race, so the symbolism packed a punch – German cats hunting Jewish mice. Here the species are often random, apart from the savage dog police. But the use of animals at least lends humour to a heavy