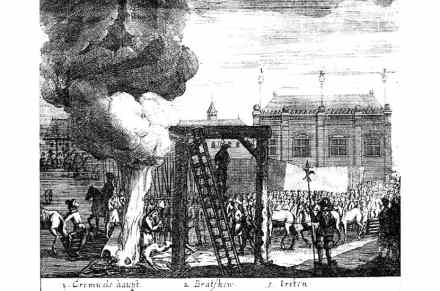

Brother against brother in the English civil war

‘The Wars of the Three Kingdoms’ is the best description of the devastating conflict that erupted in England, Ireland and Scotland during the 1640s and 1650s. While Britain lost 2.2 per cent of its population in the first world war, 4 per cent perished during these terrible 17th-century clashes. The kingdoms were, at the outset, Charles I’s. At a time when even a great leader would have struggled to navigate the political, religious and social torrents confronting him, the king was weak and apt to act on the latest advice he received; his only strengths were piety, art patronage and being a loving husband and father. When a ruler of