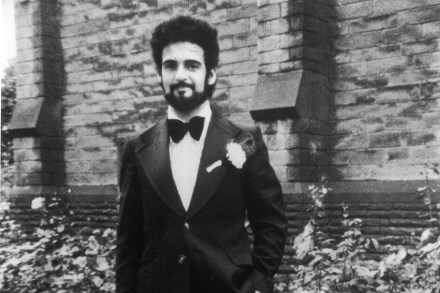

Keeping a mistress was essential to John le Carré’s success

Adam Sisman is sensitive to the charge that a book about an author’s unknown mistresses is simply an exercise in prurience. ‘I am not one of those who believes sex explains everything,’ he declares defensively. An affair with the wife of a close friend led to the ménage depicted in The Naive and Sentimental Lover But this admirably concise volume justifies its title. Sub-themes such as the practice and ethics of biography, and the emotional toll taken by spying, run through it. But its core relates how, when writing his 2015 life of David Cornwell (John le Carré’s real name.) Sisman was prevailed upon to delete details of his subject’s