Until Tuesday, I’m once again working as a junior doctor: trying to remember how to take blood, print labels, and manage being bleeped by three wards at once, two of them by mistake. For my troubles, I’ll be earning £200 an hour – a rate far above standard consultant overtime. I’m taking a fat fee from the NHS to fumble through chores a junior could do better.

As you spend hours waiting to be seen by an overstretched medic moonlighting as a junior, remember this: the strikes are completely avoidable

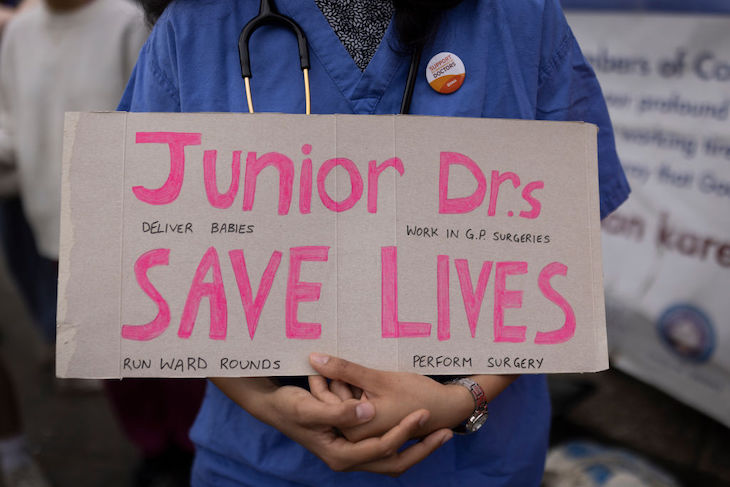

Yes, junior doctors are on strike again – and the depressing thing is how preventable this walkout is. No money was needed; the NHS could have avoided the costs and harms of the strikes, and even come out ahead. That it didn’t is a fine example of how Britain contrives to fail.

Juniors’ wages really have fallen in real terms, but only the militants think now is the right time to get that problem fixed – and strikes can’t continue without majority support. Most junior doctors I’ve spoken to are aggrieved about pay, but they accept another big rise isn’t realistic. What angers them more is the cock-up that’s been made of workforce planning. If junior doctors had fair and predictable career progression, I believe the strikes would stop. Pay matters, but being able to see a future matters more.

There was a time when Britain did a good job of ensuring its healthcare system was well run. Medical schools turned out almost as many doctors as we needed to fill our training posts, and the balance could be made up by graduates from overseas. The Resident Labour Market Test required employers to try recruiting in the UK first. But in 2020, doctors were made exempt from the test. British graduates found themselves locked out of a future in their own profession. Juniors found it hard to get jobs as posts went instead to overseas graduates.

Had this meant we got the best of the best, the system would have been admirable, even if domestic graduates were harmed. But concerns about discrimination when it came to awarding jobs meant the shake-up didn’t work particularly well; the pursuit of fairness made it harder to discriminate good from bad.

The old selection processes for doctors gave certain people advantages – usually the better ones, but not always – so, naturally, over the years, they were watered down. Recruitment has effectively been made half random, with spreadsheets standing in for judgement, and the points that mean prizes not always reliably representing quality.

Completing a ‘quality improvement project’ – beloved of some NHS managers – to reduce unnecessary electronic alarm noise in hospitals in Darkest Peru gets you somewhere in our NHS, even when the alarm noise wasn’t reduced; seeing twice the number of patients of everyone else during your casualty shifts in Luton, and doing it well, gets you nothing. I’m not raising concerns about Paddington, should he take up medicine – virtually all NHS quality improvement projects are performative nonsense – but the more distant someone’s experience, the less likely it is to be relevant.

Instead of accepting that all systems have flaws, we destroyed one for recruiting medics that mostly worked. Putting the right doctors in the right posts matters. What private company would fill important posts without interviewing people properly, and making a serious effort to judge their quality?

The solution to the workforce issue is simple, available, and not being taken. As so often, the government is behaving as though its hands are tied by legislation when it is the body that makes legislation. We are being made to serve laws when laws should serve us.

The NHS’s recent Ten Year Plan notes ‘the 2020 decision to open competition for postgraduate medical training to international trainees…[means] competition ratios for postgraduate places increased from 1.9 applications per place in 2019, to nearly 5 per place in 2024’. It commits to working ‘to prioritise UK medical graduates’. But rather than making that happen, or explaining how he will, Health Secretary Wes Streeting has offered small increases to the number of training spaces overall. This is the wrong solution to the wrong problem. A man who wants to become prime minister should do better.

Twenty years ago, when I sat on the British Medical Association’s Junior Doctors’ Committee, I would not have believed that good workforce management could be so needlessly destroyed. That interviews and references might be deemed less important than badly designed tick-box applications. That job awards could become almost half-random. That juniors would lose control over where they worked. That, having expensively trained medics, the government might not even offer them a job at all – replacing them with people from overseas who are not guaranteed to be better and are often, in fact, worse. Don’t get me wrong: many overseas graduates are superb, but some of the foreign doctors I have met in hospitals have made me deeply suspicious of the recruitment process.

So, if you find yourself in a hospital this weekend: good luck. And as you spend hours waiting to be seen by an overstretched medic moonlighting as a junior, remember this: the strikes are completely avoidable. Past and present governments have damaged the medical profession and insisted they can’t fix problems created by their own rules because their rules say they can’t. Britain isn’t ungovernable; it’s just ungoverned.

Comments