There are several class actions going on against developers of Large Language Models. Jodi Picoult, George R.R. Martin, John Grisham and several other well-known authors are among those engaging in long-drawn-out lawsuits with tech companies such as Meta (who developed the chatbot LLaMA), OpenAI (who developed ChatGPT) and Google DeepMind (who developed Gemini). These companies, without seeking permission (imagine!), used books, newspapers, websites and other text sources to generate datasets to train their machines. The lawyers for these tech companies claim it was ‘fair use’. No one actually copied and resold anything, they say; it was used to train, and only to train.

One of my novels was ‘scraped’ by Meta, and features, in a tiny way, in the lawsuit. (If you have published a book, or anything else, you can check whether it was scraped at the Atlantic website.) Why Meta chose that particular novel slightly intrigues me, but the reasons are probably very mundane. The publisher, Old Street, might have released some sort of digitised preview I was unaware of; the novel might have been the right length for the scraper; the text might have had toothsome metadata; or the scraper might have had the hots for my novel’s file extension. The experience of being pirated in this way – so that my words are being echoed, remotely, in responses to people’s questions about recipes or the meaning of life – was like having thieves break into my house and stealing not the cash on my desk, but my old A-level art portfolio.

The question is this: what if the ‘fair use’ defence fails in court? What if LLM developers are left, like schools with sold-off playing fields, with nothing to train on?

LLMs mimic creativity by combining disparate bits of the works of the past. It looks like genuine creativity because the datasets are so colossal, and the strange thing is, it will very probably look enough like genuine creativity in future to generate texts that will sell as mainstream novels or biographies. Many book-buyers are not very discerning, as a visit to your local charity shop will show you. But essentially it’s pattern recombination plus ‘constraint satisfaction’, which is the ability to write about an evening at the Hollywood Bowl in the style of The Golden Bowl.

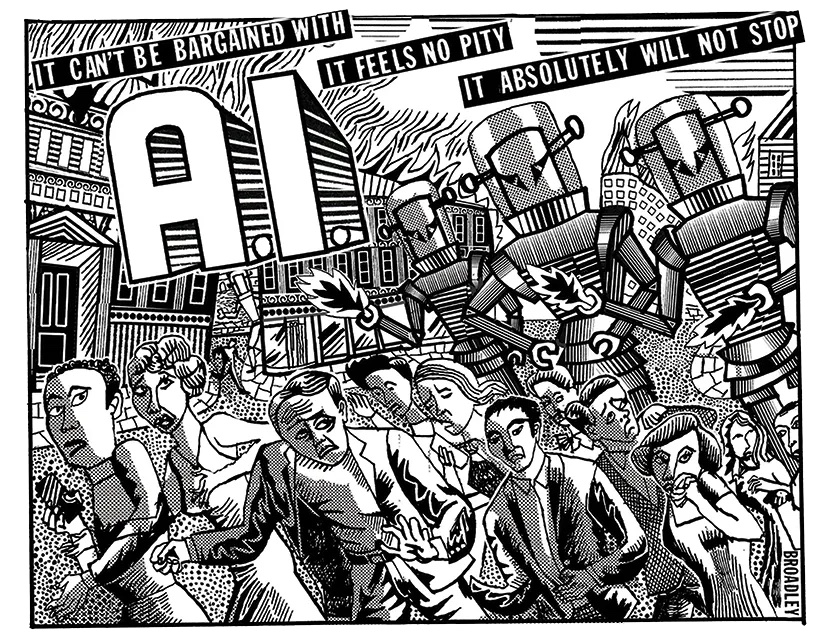

In order to continue doing this in future, to stay ahead of their competitors and feed the ever-hungry data-gut, LLM developers will need to scrape, scrape and scrape again. But there will be nothing to scrape. ‘Data exhaustion’ has set in: all the biggest public databases have already been plundered. The datasphere is now like the statue at the end of The Happy Prince, scraped bare of his gold leaf. So what will they do?

Well, one way forward might be to persuade publications with large catalogues stretching back centuries (no names, no pack-drill) to sell their millions of accumulated opinions. OpenAI has already signed agreements with Associated Press, Axel Springer (Politico, Business Insider), Le Monde and others. This solution uses explicitly licensed and/or commissioned data to fill the gap. Expensive, and a new economy, in fact: the content economy.

All the biggest public databases have already been plundered. The datasphere is now like the statue at the end of The Happy Prince, scraped bare of his gold leaf

Another might be for AIs to read what AIs have already written, they having read what AIs have already written, having read what AIs have already written, turning literature into an endlessly self-referential midden. This is known euphemistically as ‘synthetic data generation’. It’s obviously a dead end, and a rather smelly one. Of course, some may say this began shortly after Mr Gutenberg had his brightest idea.

But imagine a future in which individuals were involved. In this scenario, stupendous factories might be built in which herds of ill-paid workers mumble their life stories into microphones. It would be like the Matrix, but instead of being repurposed as batteries, humans would be experiential ore. The textures of their thoughts and feelings and memories, their moral dilemmas, their successes and failures, their confessions, would be harvested to generate the convincing content the machines cannot give birth to themselves. A paradox might emerge: in order for the machines to sound more human, the human workers would themselves be dehumanised.

Or perhaps this is all a bit Brazil. Perhaps this content could be read directly from human brains using some sort of Elon Musk-style headset. People would be sent out into the streets to have social interactions: fights and grotesque love-encounters would be the most highly paid data. In this neural farming, interiority itself would be scraped and sold (and resold, and resold). After automata take over human intellectual work (doctors, lawyers), and, a little after that, human physical work (electricians, farmers), it might be the only thing human beings can offer for monetary gain.

Having said that, though, perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad sitting at a desk for eight hours a day, with 20 minutes for lunch and restricted toilet breaks, babbling of whatever occurs to you. Everyone likes talking about themselves.

Comments