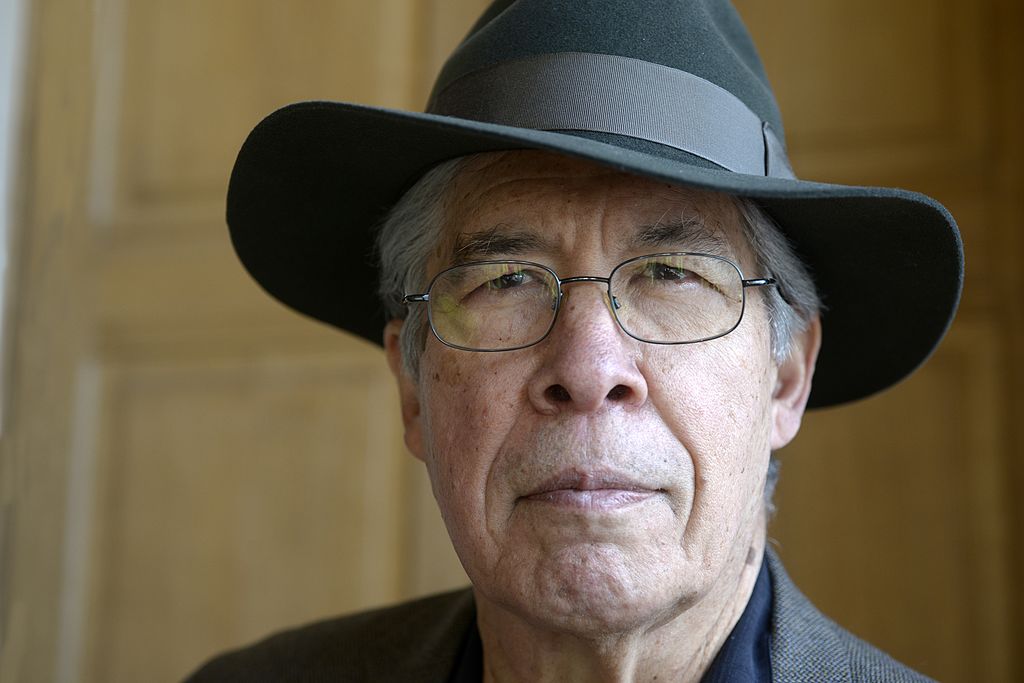

It’s an awkward time in the upper echelons of the Canadian cultural establishment. It’s come to light that influential indigenous author and former broadcaster Thomas King, isn’t actually indigenous at all.

It matters, because King has spent much of his 82 years claiming to speak on behalf of the indigenous peoples of North America, and his role in shaping Canadian perception of their First Nations has been enormous. His books have served as standard texts in Canadian schools and universities for over 20 years.

When King came to Canada, he was able not only to dine out on his purported indigenous background, but to make it the central facet of a lucrative career

Born in the US, King came to Canada in 1980 to teach native studies at the University of Lethbridge. His claim to be indigenous was made in all good faith, he says, believing on his mother’s say-so (but little other evidence, it seems) that his father, who abandoned the family early on, was part Cherokee.

Whether it was in good faith or not, when King came to Canada, he was able not only to dine out on his purported indigeneity, but to make it the central facet of a lucrative career. He taught indigenous studies, but also wrote books about being indigenous. They were acclaimed and assigned to curriculums across the country, partly, perhaps, for their quality of writing, but chiefly for their subject matter and authorship. Shakespeare was crowded out of the classroom, but there was still room for Thomas King.

Awards and literary prizes were heaped upon him, including some earmarked for First Nations’ writers; this is Canada after all, where every government form invites you to check the First Nations box for preferential treatment. His work made it to radio and screen, and he became a darling of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, hosting The Dead Dog Café Comedy Hour and appearing as the first indigenous speaker at the prestigious Massey Lecture series. His promotion to Companion of the Order of Canada in 2020 recognised him for ‘enduring contributions to the preservation and recognition of Indigenous culture, as one of North America’s most acclaimed literary figures.’

King was about to break into the world of opera with an adaptation of his Indians on Vacation novel when news broke that he was, after all, just an ordinary writer like everyone else – and the Edmonton Opera decided to cancel.

It seems there had been rumours for years that King wasn’t really indigenous. In the end, it was the genealogists at the Tribal Alliance Against Frauds who got to him, an indigenous organisation dedicated to outing ‘Pretendians’, though King says he doesn’t deserve to be classed with that group, because his was an honest mistake. He accepts the Tribal Alliance findings, he announced in an op-ed published in Canada’s Globe and Mail – a masterpiece of damage control that seemed to leave most readers feeling not outraged but sorry for him, if the comment section is any indication.

When you look at the cultural impact of his work, however, it’s hard to be sorry that he has now been discredited. The work of Thomas King is not calculated to spread peace among the nations.

Take this bit from The Inconvenient Indian, which was for a time one of the most widely read books in Canada: ‘Whites want Indians to disappear, and they want Indians to assimilate, and they want Indians to understand that everything that Whites have done was for their own good because Native people, left to their own devices, couldn’t make good decisions for themselves.’ Er, all white people want this? How does he know?

Or this tendentious passage, about the attitude of Europeans to natives: ‘By the late nineteenth century, the Indian Problem was still a problem… Yes, most of the tribes had been safely locked up on reservations and reserves. Yes, Indians were dying off in satisfying numbers from disease and starvation. Yes, all of this was encouraging…’

Far more egregious is King’s treatment of residential schools. He alleges, without a source, that ‘up to 50 per cent’ of the estimated 150,000 children who attended residential schools in Canada ‘died from disease, malnutrition, neglect and abuse.’ But this now appears to be wildly inaccurate. According to subsequent research presented by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, of which King would certainly have since seen, the proportion of children who died of any cause while attending residential schools was between 2 and 4 per cent. That’s an enormous difference. A journalist in 2017 called him out – but this writer was unable to find any acknowledgement of the error.

This is propaganda, not history. Yet The Inconvenient Indian was read and reviewed favourably everywhere. And consider the consequences: how quickly Canadians believed the unsubstantiated mass grave narrative that swept through the media in 2021, and how easily the Canadian government shrugged off anti-Christian attacks and said the anger which led to the burning of over 100 churches was ‘understandable’. Even today, a Canadian MP wants to make ‘downplaying’ the residential schools deaths a criminal offense.

King says he’s not going to apologise for sincerely presenting himself as indigenous. All right, but what about an apology for saturating Canada with ahistorical propaganda? That would be far more to the point.

Comments