At the dawn of my stellar journalistic career I served for two years as Crown Court correspondent of the Cambridge Evening News, and every working day would dutifully cycle to the city’s Guildhall to witness juries deciding the fate of the unfortunates who appeared before them.

With that experience, I have more than an amateur interest in Justice Secretary David Lammy’s reported plan to scrap jury trials in all but the most serious cases, such as murder, manslaughter and rape, and replace juries with courts presided over by judges. Lammy’s motive is said to be the need to clear the vast backlog of 80,000 cases currently awaiting trial, as justice delayed is famously justice denied, and the legal system is notoriously slow moving and cumbersome anyway.

Lammy is already facing a storm of criticism over the plan from the legal profession over his memo and there are dark suspicions that it was deliberately leaked to distract attention from Rachel Reeves’ punishment Budget.

In my time at Cambridge the court was presided over by a ferocious old judge named David Wild who was the very model of an old fashioned, politically incorrect figure who was far from shy about directing juries towards reaching the required verdict – usually ‘guilty’.

Wild made excellent ‘copy’ from a journalist’s point of view, since he was prone to making unscripted colourful and ‘controversial’ comments from the bench, and was once rapped over the knuckles by his judicial superiors for telling a defendant from the Middle East that lying was endemic in his culture.

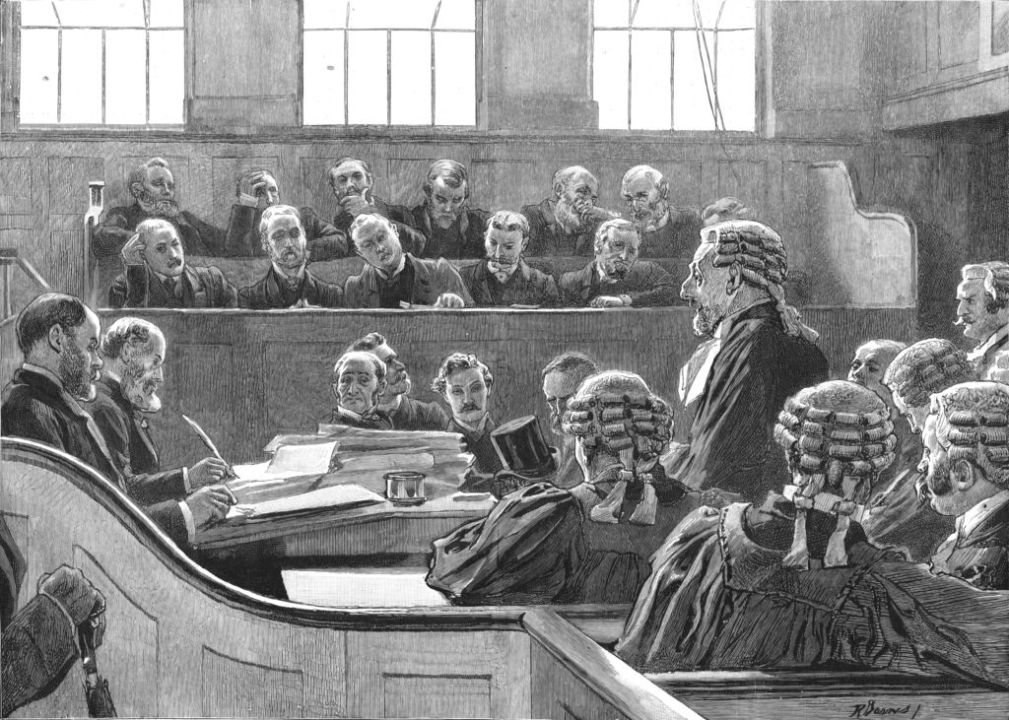

For those who have never served on a jury or seen them in action, the system is that a panel of ordinary people arrive at the court at the beginning of proceedings from whom 12 are selected at random to hear a trial. Back then, the defending barrister had the opportunity to veto any juror they don’t like the look of, though this safeguard was limited to three objections, until it was abolished entirely in 1988.

Cambridge was a court without the power to try murders, so the most memorable case I witnessed was the lengthy trial of a fantasist who was charged with fraudulently founding a symphony orchestra in the city without the funds to pay its musicians. I covered the case with a colleague called Alan Rusbridger (later to become editor of the Guardian) who had discovered that in a previous incarnation the fantasist had been jailed for masquerading as a brain surgeon in Norway, and had even carried out a successful operation on a patient. The defendant’s colourful character clearly took Judge Wild’s fancy, since he gave him a lenient suspended 18 month prison sentence after the jury returned their guilty verdict.

Another memorable case involved an Iranian student who had borrowed precious ancient Persian books from the university library, carefully razored out pages from them, and sold them to London antique dealers for thousands of pounds. He also received a suspended sentence as Judge Wild evidently did not set much store to the value of old books.

Since Cambridge has a generally high end, well-educated demographic, the juries that I observed took their duties seriously, listened carefully to the evidence and (as far as I could tell) returned fair and just verdicts, not always following Judge Wild’s pointed directions in his summing up. I saw no evidence of wandering attention or ever heard the sound of snoring coming from the jury box, even during the excruciatingly boring passages that always take up much of the time during trials.

During lunchtime adjournments, jurors, barristers and journalists would mingle at the Eagle, the nearby pub famous as the place where scientists James Watson and Francis Crick had announced in 1953 they had solved the secret of life, after discovering the double-helix structure of DNA. Although jurors are strictly forbidden from discussing the cases they were trying, drink would sometimes loosen tongues, and it would be possible to gauge the way their thinking was moving.

Jury service originated in England in the reign of King Henry II in the 12th century. It may well be asked whether the wisdom and judgment of David Lammy – a man who told the world on Celebrity Mastermind in 2008 that Henry VIII was succeeded by Henry VII – is sufficient to overturn the legal rights and protection under which all Britons have lived for so many centuries.

Comments