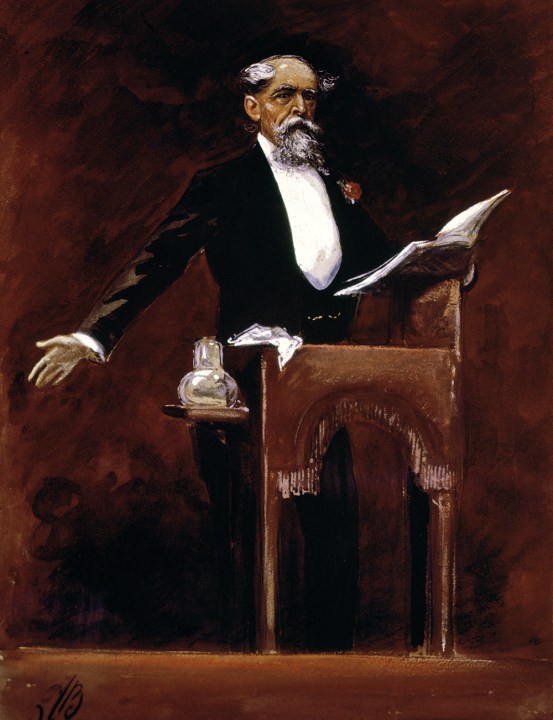

As Charles Dickens lay in his coffin, his will was read out to the assembled mourners. ‘I conjure my friends,’ he sternly instructed them, ‘on no account to make me the subject of any monument, memorial or testimonial whatever.’ It’s an appeal that later generations have studiously ignored, as can be seen in the piles of commemorative merchandise that are available to purchase online. These range from a fully poseable Dickens action figure (‘with quill pen and removable hat’) to a T-shirt featuring his face and the slogan ‘I put the lit in literature’.

They can also be seen in the shelfloads of biographies and critical works published every year. Indeed, if a mark of an author’s success is that more books are written about them than bythem, then even the prolific Dickens has a good claim to being one of the most successful authors of all time. But it is still worth pausing over the phrase ‘I conjure my friends’, because it reminds us why he is such a remarkable figure in the history of storytelling. He is a literary enchanter.

By the time of his death, Dickens – who also liked to refer to himself as ‘Boz’, or ‘the Inimitable’, or ‘the Sparkler of Albion’ – had attracted a new nickname: ‘the Great Magician’. That may have been partly a crafty wink at his love of stage magic, which led him to commission articles for his journal Household Words on subjects such as ‘Out-Conjuring Conjurers’.

It was also reflected in the time he spent practising conjuring tricks like ‘The Pudding Wonder’, which involved him pouring various ingredients into his hat before – ta-dah! – tipping out a fully steamed pudding. After visiting a London magic shop, he made several appearances at family parties as ‘the Unparalleled Necromancer Rhia Rhama Rhoos’. He also performed a trick known as the ‘Pyramid Wonder’, which he claimed to have bought from ‘a Chinese Mandarin, who died of grief immediately after parting with the secret’. He even introduced a few disguised magic tricks into his fiction. In The Old Curiosity Shop, a servant daydreams, dipping pieces of orange peel in water and pretending that this has turned it into wine; in Bleak House, Krook’s spontaneous combustion is like a vanishing act gone wrong.

Yet when it came to assessing the importance of magic in modern life, Dickens held what was not a fixed position so much as an ongoing quarrel with himself. He yearned for enchantment (he remained a lifelong enthusiast of fairy tales and pantomimes), but was angered by ‘humbug’ and scams. He was committed to the world of factual necessity, but was equally bound to one of imaginative possibility. Put another way, Dickens was as confused about the world and his place in it as most of his readers. The key difference was that he transformed his confusion into art.

He would pour various ingredients into his hat before – ta dah! – tipping out a fully steamed pudding

He could conjure up a fictional alternative that to many readers seemed as real as their own existence – so full of the sights, sounds and smells of London that the pages seemed to come alive in their hands. At the same time, he often reworked his surroundings to fit the shape of his imagination. Indeed, ‘conjuring’ his friends not to fall in with conventional expressions of grief was fully in line with his lifelong refusal to take anything for granted. Whether he is describing an assortment of dead babies, who are laid out like ‘pig’s feet, as they are usually displayed at a neat tripe shop’, or remembering his first funeral as a child, Dickens repeatedly makes the world into a place that is full of surprises. At that funeral he noticed the adults trying to keep in step with the undertaker and ‘felt that we were all making game’. (Both of these examples are taken from his essay collection The Uncommercial Traveller.)

To this extent, Peter Conrad’s decision to write about Dickens as an ‘enchanter’ is the critical equivalent of pushing at an open door; but the success of his book lies in the fact that, unlike many critics, he recognises just how strange Dickens was. In 14 brief, punchy chapters, he ranges over the entire career to pick out some of the imaginative patterns that work their way into Dickens’s writing. Conrad notices the author’s fascination with darkness as a source of creativity, and how frequently he turns the words ‘as if’ into a form of shorthand for the magical transformations produced by his own metaphors. He even notices that ‘boyslaughter’, Dickens’s word for the destruction that had been wrought on certain aspects of his childhood, only needs a small tweak to be turned into ‘boy’s laughter’ – one of the most important resources he had for fighting off unhappiness as an adult. In fact, there is little Conrad doesn’t notice, making his book seem less like a traditional critical account than the result of someone who has managed to get inside Dickens’s head and have a good rummage.

Readers who have come across The Violent Effigy, John Carey’s brilliant 1973 book about Dickens’s creative obsessions, will be familiar with this method, and maybe even with some of the examples. (Both critics draw attention to clothes, which take on a life of their own in Dickens’s writing; both spot his peculiar obsession with wooden legs.) Anyone without a good working knowledge of Dickens’s career may feel themselves getting left behind as the examples pile up. But Conrad’s enthusiasm means that even readers who aren’t quite sure where they are going are still likely to enjoy the journey.

For Conrad, this journey involves more than just a cool critical assessment of Dickens’s storytelling skills. It’s personal. When he was a schoolboy in Australia in the early 1960s, he recalls, reading Dickens allowed him to imagine ‘something beyond that place and time’, as books do for David Copperfield; and during the pandemic he re-read the complete works in a period of peculiar loneliness. ‘The novels re-enlivened a locked-down London,’ he writes. They allowed him to inspect the lair of a taxidermist who also articulates human skeletons; a suburban villa with its own little moat; and ‘a hundred other caverns of fantasy’ without ever needing to leave home. Thanks to this generous tribute to one of his literary heroes, the same is now true for Conrad’s own readers.

The author of Dickens the Enchanter, Peter Conrad, joined the latest Edition podcast to discuss the influence a love of magic had on the great writer:

Comments