-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Why are we so squeamish about describing women’s everyday experiences?

The way that language is shaped by the facts of biological sex is a rich subject. (The way that biological sex is framed, and sometimes refuses to be shaped, by language is perhaps one for another day.) Some languages have evolved forms which are distinctly those of male or female users. Japanese has speech patterns described as male or female, such as (male) the informal use of da instead of desu. There are scripts used exclusively among women, such as the syllabic Nüshu in Hunan, China. Many languages have gendered grammatical forms in ways that are not just metaphorical. Nouns such as ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ are masculine and feminine in French, but ‘girl’ is neuter in German. Some have masculine and feminine forms of adjectives and other parts of speech. English, on the other hand, has fewer sexed grammatical forms, largely restricted to pronouns such as ‘he’ and ‘she’. Other languages don’t even go that far. Bengali doesn’t have different pronouns for men and women at all, and Bengali learners of English often find it initially difficult to distinguish between ‘I gave it to her’ or ‘to him’ when referring to a man.

Arcane vocabulary was a disaster for simple people needing to understand what pregnancy and childbirth entailed

Those are the formal, enshrined distinctions where sex difference may be observed. There are more elusive ones, where social pressures may make themselves felt and where current anxieties start to show themselves. German, for instance, has until recently been much stricter than English about indicating whether a student or colleague is male or female. I’m informed that, comically, hipsters in Spain can’t simply declare themselves to be ‘non-binary’; they have to be non-binario or non-binaria, rendering their efforts null and void. In English, we might describe a man as a ‘bitch’ or a ‘tart’ with the intention of breaking sexual convention, but we are much less likely to be consciously aware of how rare it is to describe anyone other than a woman as ‘feisty’, say.

There is, too, the larger question of whether there are distinct ways of speaking characteristic of men or women. This may be an unfashionable topic among linguists for extra-linguistic reasons, but plenty of observant novelists have thought it worth investigating. The conventional portrait of a garrulous woman, from Tabitha Bramble to Miss Bates to Flora Finching and onwards, must have some basis in observed reality, as must the very characteristic masculine speech omitting the first-person pronoun.

Two wonderful observers, who were friends of each other, are worth quoting here. Kingsley Amis, in a bookshop, considers the titles of poems written by men and women:

Like all strangers, they divide by sex

Landscape Near Parma

Interests a man, so does The Double Vortex,

So does Rilke and Buddha.‘I travel, you see’, ‘I think’ and ‘I can read’

These titles seem to say;

But I Remember You, Love Is My Creed,

Poem for J.,The ladies’ choice, discountenance my patter

For several seconds…

Elizabeth Taylor let a character mark the distinction in typically acerbic terms:

The reason, they say, that women novelists can’t write about men is because they don’t know what they’re like when they’re alone together. But I can’t think why they don’t know. I seem to hear them booming away all the time.

Sex is a key factor in language formation, as well as an important subject for language to describe, and perhaps we now need to look at it more carefully than ever.

Jenni Nuttall has written a book full of interesting observations about semantic change and etymological development. Her field is the large body of words in English used to describe specifically female topics and experiences, such as menstruation, women’s work, childbirth, motherhood and sexual relations. There are some unexpected omissions. An investigation of the words for female family members would have been interesting, which in English are often ancient and comparatively blunt. We don’t distinguish in the way Bengali does, for instance, between a father’s sister, father’s brother’s wife, mother’s sister and mother’s brother’s wife – they are all simply ‘aunt’. The book is dedicated ‘to my daughter’, and a discussion both of the ancestry of ‘daughter’ and some peculiar etymological speculation in the past would have been good. Scholarship in less enlightened times has connected ‘daughter’ with the Sanskrit duhitr, which appears to mean something close to ‘milkmaid’.

Nevertheless, Nuttall’s investigations yield much interesting history, and give rise to some general thoughts. A lot of the vocabulary for women’s experiences and quite ordinary facts emerge from euphemisms, or from the decent obscurity of learned languages. Most body parts are very ancient words – ‘neck’, ‘arm’, ‘foot’ and ‘hand’ are Old English. There do seem to have been a few Old English words for women’s private parts, but the meaning of cwith is unspecific, and it died out long ago. What replaced it were frank obscenities, which have often remained obscene, and learned Latin words such as ‘vagina’. Evidently these were always things which were not meant to be named. Much the same could be said about menstruation, except that here a large body of fairly jocular terms has been recorded over time. In a book which is inevitably concerned with the way men, and the authorities in general, labelled women’s lives, this area by contrast often suggests women talking to each other in private, and making jokes about it.

Scholarship once connected the word ‘daughter’ to the Sanskrit ‘duhitr’, meaning something close to ‘milkmaid’

How many people understood the formal medical words is a good question. There’s evidence from a lawsuit early last century that the word ‘clitoris’ was unfamiliar to the majority of ordinary people, and the same must have been true of some recondite sexual vocabulary – I doubt whether ‘gamahuche’ was ever widely understood. This evidently matters much more when we start talking about facts such as pregnancy and childbirth – the arcane words must have been a disaster for simple people needing to understand what would happen to them.

This is an entertaining and an interesting book, though it might have benefited from being more clearly defined. Since it is about words, it would perhaps have been better to have cast it in the form of a dictionary, exploring individual verbal histories, like Raymond Williams’s Keywords. The narrative structure tempts Nutall into discussions of more general women’s issues, which are certainly deeply felt but which don’t add to the focus. I sometimes felt that a word she was exploring was not primarily female-orientated. I strongly associate ‘dandle’, for instance, not with mothers but with rather avuncular behaviour. There is, too, the point that individual items of vocabulary will only take one so far. Is there, in fact, a characteristic female or male discourse, affecting, among other things, syntactic choices? It would be bold to dismiss the belief of centuries out of hand.

The subject, of course, has taken on a new urgency, and Nuttall ends with the way ordinary, well-understood words, such as ‘woman’ itself, have undergone a process of attempted taboo. The question of how to define ‘woman’ seemed straightforward a few years ago. Now it has apparently travelled beyond the realms of dictionary-makers and linguistic scholars. Books like Nuttall’s are a good place to start to understand what the proponents of semantic change for political purposes are trying to do away with.

Suella Braverman and the dirty secret about white guilt

The chattering classes are mad at Suella Braverman again. What’s she done this time? Brace yourselves: she said racial collective guilt is a bad idea. She said we should not demonise an entire race just because some members of that race did something bad. She said we should never engage in racial shaming. Is there no end to this woman’s nastiness?

I’m old enough to remember when comments like these would have been utterly uncontroversial. When they would have been treated as decent and progressive, in fact. Right-thinking people once railed against the ideology of collective racial punishment, against the ugly idea that the sins of the individual should be visited upon the ethnic group he or she hailed from.

No longer, it seems, judging from the audible intake of breath that greeted Ms Braverman’s insistence that racial shaming has no place in our society. It was at the National Conservatism conference in London that she uttered the incendiary words. White people, she said, should feel no guilt for the crimes committed by white people in the past.

‘White people do not exist in a special state of sin or collective guilt’, she said. ‘Nobody should be blamed for things that happened before they were born’. To my ears, this is as commonsensical as it gets. The idea that white Brits should feel culpable for a vile, cruel practice like slavery that was abolished more than 200 years ago is crazy. It had nothing to do with them.

Braverman’s words will infuriate the identitarian left, however. Because they do buy into the ideology of collective racial guilt. They do think people in the present should self-flagellate for the horrors of the past.

That’s why writers for the Guardian go on about ‘white debt’ – the need for whites to acknowledge and even apologise for British slavery. Why there is pressure on King Charles to say sorry for slavery, despite the fact that he’s never owned a slave. Why articles are published with headlines like ‘How to apologise for slavery’, advising white nations on the right way to repent for historic wrongs.

Under identity politics, white people are expected to beat themselves up for every bad thing done by white people. They’re told to ‘check their white privilege’, to repent for their original sin of racism.

‘White Christians’ must ‘repent of our own prejudices’, as the Archbishop of Canterbury said in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in 2020. As if every white – including the little old lady who worships in a CofE village church – bears some kind of collective responsibility for that terrible American crime.

And yet we’re expected to believe that Braverman, with her critique of collective racial guilt, is the bad person, while the modish left, with their belief that all white people should do penance for the wrongs of others, are the good people.

There’s a delicious irony here: the right-on activists who damn Braverman as a racist pox on British society behave in a far more racist way than she ever has. Braverman’s articulate stand against the fashionable rehabilitation of racial shaming is anti-racist in the real meaning of that phrase.

Here’s the twist in this tale. The reason some will be bristling at Braverman’s takedown of white guilt is because they like feeling guilty. Confessing their white privilege makes them feel good. In fact, racial self-loathing, bizarrely, has become a shortcut to the moral high ground for the well-connected.

This is the most important thing to understand about white guilt: it’s a moral boast disguised as racial remorse. In checking their privilege, in expressing regret for the crimes of their forefathers, in apologetically saying ‘As a white person’ before their every utterance, the white middle classes are really advertising their heightened moral sensibilities. They’re making a big, noisy display of their superior levels of racial and social awareness.

It looks like they’re saying, ‘Oh God, I’m white, how awful’, but really they’re saying: ‘I am a virtuous person. I am a special person. Behold my righteousness.’

In a sense, white shame is the new white pride. It’s the means through which well-educated white people demonstrate their social superiority to others, to the less racially aware, to the gammon and the chavs.

It provides them with the tingle of moral superiority in relation to black people, too. There’s a saviour complex to these nauseating theatrics of white guilt. Guilt-performing liberals fancy themselves as the therapists of the black community, arrogantly believing that their mawkish, self-serving displays of historic regret will help to fix those allegedly wounded people.

This is the dirty secret of white guilt. It recreates the unequal relationship between whites and blacks, only in this instance the whites are not oppressing black people but rather are delivering them from their sad, broken state by telling them how sorry they are for old white crimes. It is breathtakingly paternalistic.

Hence the discomfort with Braverman’s stinging aside against white guilt. White guilt is the soapbox from which the new elite signals its specialness and builds up its cultural power. They cannot believe an uppity woman like Suella might take it away from them.

Why is Nicola Sturgeon wading into the jury-less trial debacle?

Nicola Sturgeon’s sheer brass neck never fails to amaze. A politician whose party is under police investigation, and whose husband has recently been arrested, is hardly best placed to start talking about scrapping juries in criminal trials. It’s a bit like Boris Johnson, at the height of partygate, speculating about the breaking up of the Metropolitan Police.

Sturgeon’s first venture into policy advice since her resignation came in a column in the Guardian supporting First Minister Humza Yousaf’s proposed Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill. This bill, which she sponsored before she resigned in February, calls for a trial of judge-only specialist courts for sexual offences.

The right to trial by jury has been the cornerstone of the Scottish justice system for centuries and the bill has been bitterly opposed by the legal profession. Over 500 solicitors from bar associations across Scotland have threatened to boycott the experiment on the grounds that it is based on the premise that rape victims are not getting a fair trial. The former Supreme Court judge, Lord Hope, has criticised the legislation as a threat to judicial independence. Frances McMenamin, one of Scotland’s most senior female KCs, says that removing ‘democratic participation’ would affect not only accused persons but ‘the rights of every citizen in Scotland’.

Politicians may be under pressure from lobby groups to have more men jailed for these terrible crimes, but that is scarcely a justification for abandoning the presumption of innocence.

Sturgeon claims that people who serve on juries are steeped in ‘rape myths’. That jurors often believe that women who are ‘dressed a particular way, or had been drinking, or in a relationship with her alleged attacker, must be at least partly to blame’. She gives no evidence for this slur on the integrity of citizens who sit on juries. Jurors in Scottish rape trials are given guidance by the judge and are provided with a manual on how to assess evidence.

Her Guardian article also asserts that the conviction rate of 51 per cent is too low. Rape prosecutions are inherently difficult because they often involve ‘he said/she said’ testimonies from people whose memories may be clouded by drink or drugs. Without corroboration, it is difficult to establish guilt beyond reasonable doubt. Politicians may be under pressure from lobby groups like Rape Crisis Scotland to have more men jailed for these terrible crimes, but that is scarcely a justification for abandoning the presumption of innocence.

The bill, which also abolishes the ‘not proven’ verdict and gives lifetime immunity to complainants in sexual offences cases, was inspired by a report in 2021 from the senior Scottish judge Lady Dorrian. She presided over the trial in 2020 of Nicola Sturgeon’s bête noir Alex Salmond for sexual assault and attempted rape. This landmark case forms the inevitable backdrop to this radical reform.

A jury of eight women and five men acquitted Salmond of all 13 charges in March 2020. In the subsequent Holyrood inquiry, Ms Sturgeon made clear she did not accept that the women who had accused him had been lying or had been misguided. She said that she felt ‘physically sick’ when she was informed of the allegations against her predecessor. She also condemned Salmond for his ‘deeply inappropriate behaviour’ adding that ‘as First Minister, I refused to follow the age-old pattern of allowing a powerful man to use his status and connection to get what he wants’.

Last month it emerged that the Crown Office has launched a perjury inquiry into what was said at the trial after representations from Salmond’s legal team. His accusers were senior figures in both the Scottish National party and her government. Nicola Sturgeon cannot therefore claim to be a disiniterested observer in the move to hold trials of judge-only trials for sexual offences. Indeed, you could argue that she should recuse herself: she has a direct and very personal interest.

But now of course Sturgeon is a mere backbench MSP, albeit an influential one. She is clearly not allowing her present legal difficulties to silence her. Ms Sturgeon’s arrest over the ‘missing’ £600,000 in donations has been expected for weeks. She was one of the three signatories to the problematic 2021 SNP accounts, along with her husband, SNP chief executive Peter Murrell, and the party treasurer Colin Beattie, both of whom have already been arrested and released without charge pending further investigation.

Yesterday, it was reported that that Operation Branchform, which involved the erection of a sizeable forensics tent outside the former First Minister’s Uddingstone home, may have been delayed by the Crown Office until after the SNP leadership election in April.

Of further interest is the fact that the prosecution service in Scotland is headed by a political appointee: the Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain KC. Labour’s deputy Scottish leader, Jackie Baillie, has claimed there could be a ‘conflict of interest’. Ms Bain, who was appointed by Nicola Sturgeon, has also endorsed the trial of jury-less trials. It doesn’t take Inspector John Rebus to detect something here that may not look entirely savoury.

Britain is becoming Brussels on Thames

Whatever happened to Singapore on Thames? Weren’t we, after leaving the EU, supposed to be forging a future as a deregulated, low-tax, business-friendly enclave situated 20 miles off Calais? It isn’t quite looking that way at the moment. We are reinventing ourselves as Brussels on Thames – only more so.

Do our bureaucrats really need to come down so heavily on big players in the realm of cloud computing games?

Our corporation taxes are rising at a time others are static or falling, we keep inventing new regulations which far outdo EU regulations – such as that allowing new employees to demand flexible working. We are ploughing ahead with green measures such as the ban on petrol and diesel cars from 2030 while the EU has allowed some flexibility. And now comes Microsoft’s planned acquisition of computer gaming company Activision – which EU regulators have just approved while our own Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) continues to block.

No country, it has to be said, has unfettered capitalism – indeed, US competition authorities have also blocked the Activision deal for now. There is a good case for supporting the blocking of mergers and acquisitions where it involves essentials such as food, utilities and so on. It makes sense to enact competition law when one company is trying to control the supply of a commodity, or squeeze out competition by buying up development sites, or with the banking system, where agglomeration can create institutions so large that they become too big to fail.

But do our bureaucrats really need to come down so heavily on big players in the realm of cloud computing games? It is hardly as if Microsoft – or anyone else – has, or could possibly have, a complete grip on the market. Call of Duty – which is apparently an Activision game, for anyone who is interested – might be popular now, but we know full well that that next year gamers will have moved on to something else.

Regulators will look as silly as if they had made a great fuss about regulating the price of a game of Space Invaders. There are matters on which it is better simply to let the big bad world of capitalism get on with it.

Even the great bonfire of EU red tape has turned out to be more of a stubbed-out fag in an ashtray. The regulations to be dumped have been reduced to a list of obsolete laws which Brexit has rendered meaningless anyway. At some point the government is going to have to come up with some great benefit to demonstrate that the pain of Brexit was worthwhile – and no, it can’t keep quoting the vaccine procurement programme. At present, it is failing miserably. We are recreating ourselves as a pale imitation of the EU – and just at the time that the EU itself is finally coming round to realising that lighter-touch regulation can invite investment and enterprise.

How the Conservatives can win again

There is a tension at the heart of conservative thinking today – one that the Conservative party must address if it wants to win again at the next general election. The National Conservatism conference, being held in Westminster this week, is a bold attempt to speak to this internal struggle: how to strike the right balance between the right to be free and the right to belong.

Karl Marx was right in the 19th century when he said that capitalism causes all that is holy to be profaned and all that is solid to melt into air. John Gray was right in the 1980s when he said Thatcherism would eat itself – that the free market depends on social institutions and habits that the free market itself undermines.

The job before us is to rebuild our society on the basis of the responsibilities we owe one another

But it is also true that in a well-organised society, the free market – and personal responsibility, and private property – are the things that help sustain the social order. They make possible prosperity and the virtues that we need to maintain the old ways and adapt them to the present.

Conservatives will always argue about this. But let’s not argue about which came first. We were not born free. We were born attached. Before we make our own way in the world, we belong to a family, even if for many of us that family is fractured. We are related before we are alone.

And so conservatism is not a philosophy of liberation. It is grounded in a recognition of our responsibilities to each other. In my view, our many present discontents can be traced to the abandonment of this principle in recent decades. The Brexit vote of 2016 and Boris Johnson’s victory in 2019 were reflections of a fact: that the 21st century so far has failed the people of this country.

Both those votes were rejections of the great millennial package: globalisation, liberalisation, modernisation. The progressive promise was that we should abandon the nation – abandon the family and the neighbourhood too – and everyone would get richer. Everything would get nicer. We’d be more equal, more at peace, more free.

In fact, we’re all poorer, less equal, less free, and less at peace. The progressive promise has given us 20 years of cheap credit, cheap labour and cheap imports. We’ve had an economy (the ‘butler economy’ as Michael Gove describes it) based on professional services, especially financial services: servicing the wealth of others without being too scrupulous about how they made it.

For the first decades of the 21st century, the people beyond the City were useful only as consumers. The pound was propped up by the City of London so the public could afford foreign goods while our own manufacturers suffered.

And for the jobs that need doing – in hospitals and factories and shops – we imported cheap workers from abroad. Eight million more people have been added to our population in this century because of immigration, depressing wages and imposing huge demands on the health system, on housing and on our future pension bill.

This is the economy of the 21st century so far: stagnant living standards, low growth and chronically poor productivity. We are the most spatially unequal – in terms of rich areas and poor areas – country in the developed world.

The government recognises all this and I applaud their efforts – on skills, on capital investment, on public services – to ‘level up’ the country. They’re doing the right thing, and tackling problems decades in the making. The job before us is to rebuild our society on the basis of the responsibilities we owe one another. I suggest three home truths that will help us do this, three political facts which are rooted in the attitudes and habits of the people of this country. They are national and they are conservative.

The first truth is that the job of government is to defend the interests of its citizens and indeed to privilege its citizens over those of other countries. We have our foremost loyalties and obligations to people we know. That means we cannot give sanctuary to all the world’s poor or even to all those rich or strong enough to travel to our shores. The basis of our generosity to the world – and I want the UK to be the most genuinely generous country in the world – is that we control our own borders.

The second truth is that the family – held together by marriage, by mother and father sticking together for the sake of the children and the sake of their own parents and for the sake of themselves – is the only possible basis for a safe and successful society. Marriage is not all about you. It’s not just a private arrangement. It’s a public act, by which you undertake to live for someone else, and for wider society; and wider society should recognise and reward this undertaking.

The third truth is this. Government can’t fix society. It can’t deliver social justice. But it can strengthen the conditions for justice – the conditions of virtue, that make us behave well to one another. And so the job of government is to build an economy and a civic realm, a civil society, that nurtures good people.

That means an economy built around the household and the community. We see this happening – fitfully and in part, but unmistakably. I see it in Wiltshire, where thanks to the internet and to new tech-based businesses, towns and villages left behind by industrialisation are becoming viable economic centres once again: places of trade and craft and innovation, and all the ordinary jobs that sustain a community.

We need young people to be encouraged and incentivised to seek meaningful, useful, practical trades: the vocational jobs our society needs. That means switching from funding nearly half of all school leavers to go to university and instead paying more young British people to be plumbers, electricians, and engineers.

We need public services that are accountable to local people, built on relationships, where prevention is better than cure, where we can reduce the size of government – the vast bureaucracies of the welfare state – because we have reduced the demand for government help: because people are better, families are stronger, society is healthier.

These home truths are popular because they reflect the values and aspirations of the majority of the British people. Politically, therefore, the Conservative party needs to lean into the realignment. Both 2016 and 2019 were an instruction from the public that they expect us to govern with their interests and their values in mind. Our loyalty must be to the people who brought us to power. If we honour those people, their interests and values, then they will vote for us again and we will win again.

This is an edited version of Danny Kruger’s speech at the National Conservatism conference yesterday.

Should we ignore Putin’s criticism of the West?

Not much happens in Russian families without the say so of the babushka. Russia’s high divorce-rate, and a situation where fathers are often absent and the mother out at work, makes it normal for grandmothers – who often hold the family purse-strings – to raise children themselves.

This doesn’t, of course, mean that the younger and older generation see eye to eye: babushka tends not to use the internet or understand modern technology, and might hold conservative opinions radically different from the grandchild’s. Yet there is often a spirit, in the political scientist Ekaterina Schulmann’s words, of ‘hopeless obedience’ to her.

Something similar is at play in the way many Russians view Putin. You might not like Russia’s political class and groan at their opinions but they are going nowhere. You have to humour them and give at least the appearance of complying. Putin, in fact, rather than being Father of the Nation, is – as Schulmann puts it – more like the great ‘All-Russian Babushka’.

Putin has sneered at the Church of England

In few things does this seem truer than in Putin’s attitude to Western liberalism. The West, Putin said at the Victory Parade last week, are ‘destroying family values, traditional values that make everyone on this planet human.’ He has sneered at the Church of England’s entertaining of a ‘gender-neutral God’, and accuses the West of normalising paedophilia. Russia’s mission is to ‘defend our children from monstrous experiments designed to destroy their consciousness and their souls.’ When he says these things, a collective groan goes up from the Western media. Words like ‘hysterical’ and ‘rant’ are thrown around, and Putin is accused of being ‘more angry taxi driver than head of state.’ Granny, from her rocking chair in the corner, is sounding like a mad old bigot, and we wish she’d put a sock in it.

Yet even a stopped clock, as the saying goes, tells the right time twice a day, and the West swats away Putin’s comments at its peril. Indeed, they should ask themselves frankly how much help over the past ten years they’ve unwittingly given him to stay in power. This depiction of the West – comic overstatement though it may be – hasn’t come out of nowhere and has traction. With every rainbow police car, every ‘edgy’ Sam Smith video, every sacked gender-sceptical worker or trans-bested female athlete, the Kremlin has had reason to thank us. It’s easier to present yourself as a gatekeeper if some of the things that threaten to sweep through that gate repel sufficient numbers of people – even many in the West.

Perhaps you support gay marriage but find the ubiquity of rainbow flags in Pride week a little over the top. Or consider yourself a live-and-let-live liberal but still feel nonplussed to see your local supermarket, your local takeaway, even your bank-machine vehemently supporting LGBT rights. Do you feel unease at the push in some quarters to rebrand paedophiles as ‘minor attracted persons’? Then imagine how these things seem from a country where the combined juggernaut of state, church and media is denouncing them daily and highlighting them as menacing, unwanted imports. And Russia, be assured, has been watching us like a hawk.

This became clear from the four years I spent there. What took place abroad, Russian friends told me, was never difficult to discover – the Russian news was full of it: ‘It’s finding out what’s going on in our own country that’s the challenge.’

‘What’s happening in the West?’ demanded my neighbour Galya, a pensioner who lived upstairs from me in Rostov, and though I knew she’d been tuned into anti-Western propaganda (a fact which, tellingly, affected our relationship not at all) in some ways I was asking myself the same question. What was happening? Why were Mermaids and the Tavistock clinic suddenly in the news so much? Why was a conservative government introducing proposed changes to the Gender Recognition Act, potentially the most seismic and divisive piece of legislation for decades? Why did ministers like Penny Mordaunt push the trans-agenda so vigorously? Or Sajid Javid, then Home Secretary, seem so eager to introduce new categories of hate crime, stymying our social interactions even more? Most crucially, where did you go politically when changes you were so dubious about were cheer-led even by the party whose designated political mission it was to put the brakes on them? It was all more than a little troubling.

Russia, of course, had its own problems. You knew Putin was a thug and a murderer and that his ‘managed democracy’ was a joke, but Russians lived much of their lives in another dimension – and sometimes he came out with things that felt uncomfortably close to the bone.

When he accused the West of destroying ‘its tradtional values from above’, you couldn’t dismiss it out of hand. When he said that the liberal idea had become obsolete and was no longer serving the majority of its citizens, it at least seemed worth entertaining, even if you quibbled with it – or didn’t like the messenger. When he insisted that people coming to live in Russia ‘need to realise they have to observe our laws, they have to respect our culture, our history,’ it seemed the kind of obvious statement our own politicians sometimes shied away from. It didn’t occur to you until last February – though God knows, there was plenty of evidence before, from the Salisbury poisonings to the 2008 invasion of South Ossetia onwards – that this was a rule he considered inapplicable to himself or his countrymen, when they were being the worst visitors imaginable in countries not their own.

Russia has since then stood in increasingly grotesque contrast to the West, with its new punitive laws against discussing LGBT matters in public or its proposal to label feminism a form of ‘extremism’. The Putin regime may not be abandoning its vulnerable young to the trans movement, but is killing them en-masse on the battlefields of Ukraine.

It is all too easy in the ‘us’ and ‘them’ of wartime to see only your enemy’s faults – ‘War is Peace’ as Orwell’s slogan has it – but this is self-defeating. When Putin speaks about Western shortcomings, we should interrogate ourselves about how much these are the grumblings of a querulous, agenda-driven geriatric, and how much he is simply telling us, in exaggerated form, how we appear to onlookers.

We should do this not to navel-gaze or berate ourselves but for one reason only: because in the answer to such questions lies the clue of how to beat him. Putin the grand babushka, like all babushkas, may not be long with us. Putinism, with its deep roots in the country’s psyche, will be much harder to dislodge.

The West cannot do this merely with bombs, bullets or self-righteous homilies. But it can perhaps do it by example: by reining in its more garish aspects, by working out the differences between tolerance and submission, freedom and excess, reason and unreason. And by becoming a hemisphere no longer so easy for Putin and the likes of him to ridicule, shrink from, caricature or reject.

Greens side with Tories over Labour (again)

Another set of local elections offers another chance to expose the fallacy of the ‘progressive alliance.’ Every so often, misty-eyed centrists of a certain age like to wax lyrical about Labour, the Lib Dem’s and Greens joining together to kick those wicked Tories out of office. A Marvel Universe for moderates, if you like. Sadly for such commentators, political reality has a nasty habit of shattering these illusions.

Every election produces unlikely bed fellows, offensive to those of a progressive disposition and this year is no exception. For up in Lancashire, the Greens have opted to back the Conservatives on Hyndburn Council, after this month’s elections left Labour and the Tories with 16 councillors each. Ironically, the decision of the Greens to ‘informally support’ the Conservatives was taken by its two councillors Paddy Short and Caroline Montague both of whom were Labour councillors until quitting 12 months ago.

So much for natural political bedfellows eh?

Britain’s economy is struggling with so many off sick

One of the UK’s biggest economic problems is having so many people out of work – and the slowest return to pre-pandemic workforce levels in Europe. This is costly and slows growth, as taxpayers foot the bill for benefits while employers struggle to fill vacancies. Today’s figures show that it is getting better – but slowly.

The official unemployment count crept up to 3.9 per cent in the latest statistics. This is, ironically, a good sign as it shows more people are actually looking for work (about 12 per cent of the working-age population are on out-of-work benefits, although this is a figure that ministers seldom update and never publicise).

Meanwhile, figures released this morning by the Office for National Statistics show that job vacancies have fallen for the tenth consecutive period. They’re down 55,000 but still stand at just over a million jobs. To put this into perspective, the average in the pre-pandemic decade was about 600,000.

The number of people out of work and not seeking it (economically inactive) fell too.

In fact between the end of last year and the first quarter of this year there was a record flow of people moving from the ‘economically inactive’ category to the ‘employed’ category as some 156,000 people returned to or started work. This was primarily driven by young people and students looking for work.

But there are still some 361,000 fewer people in the labour market than in the months leading up to the pandemic. That’s the economic equivalent of losing a city the size of Nottingham. This will be offset in part with the recent rise in mass migration, a trend we’ll learn more about next week when the latest figures come out.

We also see today a continued rise in those on long-term sickness, which has hit a fresh high of nearly 2.6 million. This figure has shown no sign of slowing and is now nearly 440,000 higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Public sector wages grew 5.6 per cent – the largest nominal jump for 20 years. But adjust for inflation and they’re in decline. Private sector wage growth remained at 7 per cent, also a fall after inflation. Combined, this was again one of the largest falls in real earnings power since comparable records began in 2001.

The figures have not shown enough change on last month's release to make a meaningful impact on the Bank of England’s overall fears for the economy. Added to this is inflation which is expected to fall next Wednesday as energy prices drop out of the comparison. But it will still remain higher than many had assumed at the start of the year. As a result markets and economic pundits alike expect interest rates to be raised to 4.75 per cent.

We may be seeing signs of cost-of-living pressures incentivising a shift from welfare to work, pushing vacancies down. But the nearly 2.6 million signed off as too unwell to work shows no sign of coming down anytime soon – and while five million continue to stay on out-of-work benefits (a post-lockdown scar that was not expected), the UK recovery is unlikely to speed up.

Nicola Sturgeon can’t complain about polarisation

Nobody ever accused former Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon of possessing a great sense of humour but, surely, she must be joking. Writing in the Guardian about proposed justice reforms in Scotland, Sturgeon has blamed deep political divisions for some taking fixed positions before examining the evidence.

This is like an arsonist explaining that while, yes, they may have petrol-bombed that Pizza Hut, they hadn’t expected the place to burn down

And then the killer punchline. On the issue of polarisation, Sturgeon says she had ‘underestimated the depth of the problem’.

This is like an arsonist explaining that while, yes, they may have petrol-bombed that Pizza Hut, they hadn’t expected the place to burn down.

Nicola Sturgeon has, without question, been the driving force behind the polarisation of Scots in recent years. She has othered opponents and treated the views of the majority with energetic disdain. Her actions have been entirely deliberate.

When Scots rejected the nationalists’ separation plans in 2014, the pugnacious Alex Salmond quit as SNP leader and Sturgeon stepped up, promising to be a leader for all Scots, regardless of how they had voted in the independence referendum. This solemn pledge was to last for days.

Soon, Sturgeon was gaslighting No voters, insisting they were changing their minds about independence even as polls told a very different story.

Opposition politicians were, routinely, treated with contempt. Any legitimate criticism of Scottish government policy was dismissed by Sturgeon as an example of ‘talking Scotland down.’ Any slight was defended with a boorish – and complacent – reminder of the most recent election results.

And Sturgeon was perfectly happy to make things unpleasantly personal. When former Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson lost her seat at Westminster, the then First Minister could be seen on live TV, clenching her fists and cheering like she was watching a fight in a pub car park. And then there was her take on the Tories, the second party at Holyrood and, therefore, the preference of hundreds of thousands of Scots. ‘I detest the Tories’, she said, leaving those voters in no doubt about how seriously she took their concerns.

Now, on the issue of whether there should be a pilot of jury-free trials in rape cases – a proposal rejected by lawyers across Scotland – Sturgeon writes ‘we should accept there are valid points on both sides and allow some good faith to enter the debate.’ It’s enough to make the eyes roll completely out of your head.

When, last year, Sturgeon was driving the Scottish government’s flawed plan to reform the Gender Recognition Act, she simply refused to accept that the views of anyone who disagreed were worthy of consideration. Rather, she painted women who feared the introduction of self-ID would negatively impact on same-sex spaces as cruel transphobes. Their concerns were simply not valid.

Sturgeon trashed the idea that those who disagreed with her position were acting in good faith. In fact, she said, some people were using the issue of women’s rights as ‘a sort of cloak of acceptability to cover up what is transphobia’, adding ‘But just as they’re transphobic you’ll also find they are deeply misogynist, often homophobic, possibly some of them racist as well.’ As bad faith arguments go, that’s a doozy.

If political debate is broken in Scotland – and, I fear, it is – Nicola Sturgeon cannot complain. Her boot-prints are all over the scene of the crime.

The inconvenient Palestinians

His name was Abdullah Abu Jaba and I want you to remember it because it’s the last time you’ll hear it. He was a Palestinian from Gaza, reportedly a father of six, and was killed in the latest clashes between Israel and Palestine Islamic Jihad. You haven’t heard of Abu Jaba because he was an inconvenient Palestinian, one who cannot be held up as the latest victim of Zionist aggression. Pictures of his weeping widow and confused children will not fill your social media timeline. Major media outlets will not compete to tell human interest stories about how he played with his children or how his family will cope without him. No US congressmen or British MPs will demand justice for him.

Because Abu Jaba was not killed by Israel, but by Palestine Islamic Jihad. He was a labourer and working on an agricultural building site near Shokeda, a tiny Israeli village near the boundary with Gaza, when a PIJ rocket strike hit on Saturday. He was not protected by Israel’s Iron Dome missile defence system which only targets rockets heading for populated areas. Abu Jaba and a number of other men were working in a remote field despite an evacuation order issued by the Israeli army. A father will take whatever risks are necessary to put food on the table. Abu Jaba was 34, his eldest child is said to be 11.

He was one of the 18,000 Palestinians from Gaza who go to work in Israel every day. His brother, Hamad, is another. Hamad was seriously injured in the same attack. Israel’s defence ministry has recognised Abu Jaba as a terror victim, meaning his widow and children will receive the same compensation payments that go to Israeli families bereaved by terrorism. Palestinian guest workers in Israel can encounter suspicion, hostility and racism. It’s a relief, albeit a small one, that the Jerusalem bureaucracy will do right by Abu Jaba’s loved ones.

Abu Jaba is not the only inconvenient Palestinian. Among the civilian casualties recorded in the past week were Palestinians Ahmed Muhammad a-Shabaki (51), Rami Shadi Hamdan (16), Yazan Jawdat Fathi Elayyan (16), and Layan Bilal Mohammad Abdullah Mdoukh (10). Each is believed to have perished after Palestine Islamic Jihad rockets fell short and dropped inside Gaza instead of Israel. They join other inconvenient Palestinians, such as the 14 Gazans — half of them children — killed by misfired Palestinian rockets last August, and Mahmoud Abu Asabeh. Abu Asabeh, a Palestinian working in Ashdod, was killed in 2018 when a rocket from Gaza hit his apartment building. He was 48 and had five children.

Palestinians are killed in Israeli air strikes, too. These Palestinians are also parents and children, and while there is no moral equivalence between lawful self-defence and terrorism, death is death. The difference is that Palestinians inadvertently killed by Israel quickly become faces of the conflict while you have to turn to page 27 and scan another dozen paragraphs to learn about Palestinians killed by Palestinian terrorism. The practitioners of this double standard want the world to see the Palestinians but they themselves can see only symbols, and Palestinians who lack symbolic value are of lesser interest to them. Some Palestinians just aren’t Palestinian enough for pro-Palestinians.

Western progressives aren’t alone in seeing Palestinians as symbols. To their political and paramilitary leaders, the Palestinians are archetypes, emblems of resistance and emblems of victimhood, their deaths peddled as martyrdom for the domestic audience and ethnic oppression for gullible CNN producers. Palestinians who fit into neither category lack instrumental value and may even prompt unhelpful questions about a leadership which has consistently failed its people.

So while it is tempting to see Abdullah Abu Jaba’s death as a symbol of Palestinian self-sabotage, his story was his own: that of a husband and father who worked hard for his family even as the world blew up around him. But it wasn’t enough. He needed to be someone else’s story and his death to bear a meaning it could not support. Because it couldn’t, Abu Jaba will quickly be forgotten like all the others who could not be made into symbols. He was an inconvenient Palestinian.

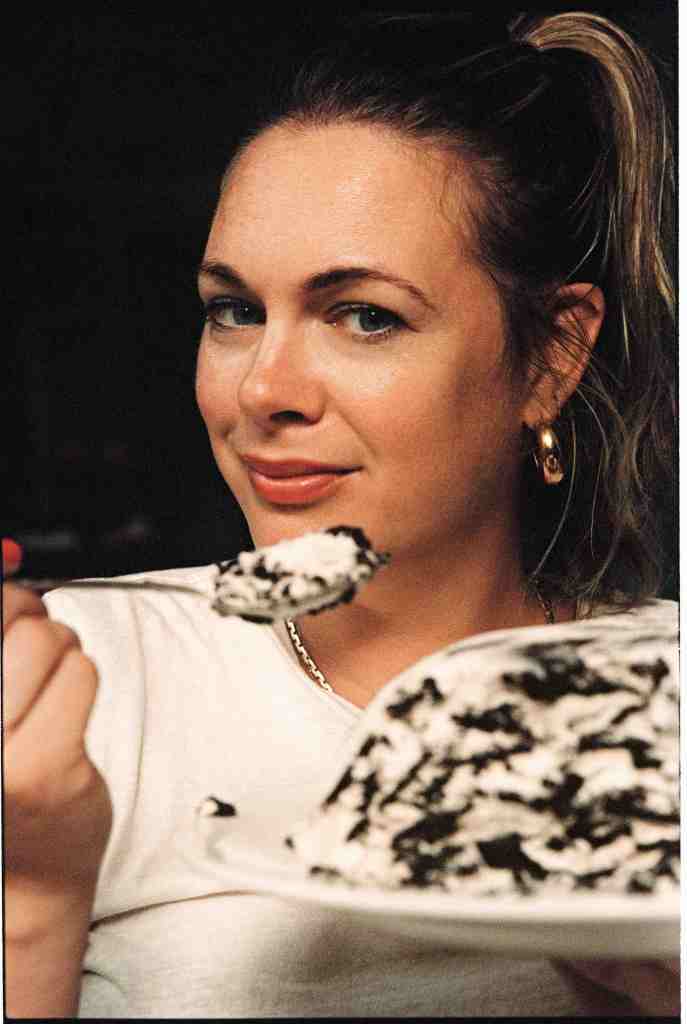

Alison Roman: ‘My desserts are consistently imperfect’

Alison Roman’s cooking is a counsel of imperfection. She serves dinner late (fine, as long as you have snacks), gets her guests to pitch in on the washing up and won’t make her own ice cream – ‘it simply will never be better than what you can buy, sorry’. ’Her ‘pies leak, cheesecakes crack and pound cakes are pulled from the oven before they’re fully baked. Lopsided and wonky, occasionally almost burned, unevenly frosted, my desserts are consistently imperfect’. In her new book, Sweet Enough, Roman wants to free the home cook from the dessert ties that bind them. ‘My hope for you,’ she tells her reader, ‘is that you strive for the animalistically irresistible, not aesthetically pristine’. The two, she finds, are ‘rarely the same’.

‘Baking is annoying. It’s frustrating. It’s hard. It’s not instantaneously satisfying. It’s so opposite of a lot of the reasons I like to cook’

Roman, 37, is the archetypical millennial food writer: beautiful and effortlessly stylish, with a Brooklyn-based lifestyle that has the same deliberately casual aesthetic as her food. She was senior food editor at Bon Appétit and had a column with the New York Times, and a host of her recipes have gone viral. She loves anchovies and lemons and shallots; her taste ‘skews salty, tart and bitter’. And her opinions are as bold as her flavours: for many, her strident, semi-serious declarations about food were as compelling as her recipes. But three years ago, they got her into trouble. She made some ill-judged comments in an interview about decluttering guru Marie Kondo and model and TV presenter Chrissy Teigen which caused a small media storm, and raised questions about her – and other recipe writers’ – use of globally established dishes without appropriate cultural attribution. She apologised, but it was too late. She lost her column at the New York Times and was, for want of a better word, cancelled. Sweet Enough is her first book since that time.

In many senses, a dessert-focused cookbook was not an obvious topic for Roman’s third book. Her first two books, Dining In and Nothing Fancy, sought to make home cooking bigger, better and more accessible, but with a firmly savoury emphasis. They included sweet stuff, but only as a final, brief chapter. Not an afterthought, but certainly not the main event. Despite beginning her career in the pastry section of big-name American kitchens – under Christina Tosi at Momofuku Milk Bar in New York, and at Quince in San Francisco – she has always come down on the side of savoury cooking. ‘If I’m given the option between a sweet and a savoury thing, I’ll choose the savoury thing every time, even at dessert time,’ she tells me. Not the obvious pitch for a book about cakes, perhaps.

‘I have a real hang-up about being a useful person,’ she explains – and desserts ‘aren’t useful’. It took her a while to realise that this is their whole charm, but once she did, it became the thumping momentum behind the whole book: ‘It felt really freeing once you realise that the whole thing is meant to be fun… I didn’t expect to love making a dessert book so much, but I really did.’ When she writes in her introduction that ‘gestures that demonstrate joy can exist just to exist’, it feels as much a personal epiphany as it does an attempt to persuade the reader.

But this pursuit of joy is not a meandering one. Roman’s character and force of opinion has not been dampened: she’s not interested in meringue, and there will be no deep-frying – ‘not in my home, anyway’. Both raisins and walnuts are banned from her carrot cake. In fact, cakes should be ‘as unfussy as humanly possible’. Her explicitly sweet cookery book includes a whole chapter on savoury dishes.

Despite her professional pastry background Roman paints herself as the anti-baker. For many years, she writes, she was not really a cake person – before launching into a 15-recipe chapter on cake. She can think of 739,275 things worth worrying about and ‘ugly pie simply isn’t one of them’. She devotes as much page space to what she hates about baking as to what she loves about it. The first photograph in the book shows a wasp eating jam from a spoon.

As we talk, she is upfront about her relationship with desserts: ‘Baking is annoying. It’s frustrating. It’s hard. It’s not instantaneously satisfying. It’s so opposite of a lot of the reasons I like to cook.’ But it’s this understanding of the home cooking conflict that, ultimately, is responsible for Roman’s widespread fanbase. That frustration that she describes is achingly familiar to the majority of people who bake. By harnessing it, she is able to disabuse her readers of their anxieties: ‘I wanted to apply the same pragmatic accessibility that I do to savoury cooking to desserts.’

‘Desserts exist just to make someone happy… there are so few things that are like that in the world’

Sweet Enough feels like, if not a fresh start, then a page being turned. This is, presumably, a deliberate move. Roman worried that after two books about, essentially, cooking supper, she was in danger of ‘churning out similar books each time, and this one felt like a distinction’. But it would be understandable if, after everything that has happened, she had other reasons for a new focus. Roman attributes any shift in tone to a combination of personal growth and the passage of time. ‘I think that I am more sure of myself. I felt the first two cookbooks were very focused on introducing the world to me. There’s a bit more security in feeling comfortable and how I present myself. Any period of time in which you’re allowed to evolve… I hope there’s a marked difference.’

But it seems like more than that. For all the strident opinions and pudding rules she imposes, Sweet Enough Roman isn’t as spiky or bolshy as the Roman of Dining In or Nothing Fancy; her edges have softened. It’s as if the change of direction to the frivolous has changed her too: ‘Desserts exist just to make someone happy… there are so few things that are like that in the world,’ she explains, with an uncharacteristic earnestness. Whether it’s intentional or sweet serendipity, a move away from the salty to the sweet is a savvy one.

Sweet Enough by Alison Roman is out now (Hardie Grant, £28).

Why are Americans buying up our castles?

You might think someone who grew up in the 356-room Belvoir Castle wouldn’t be too worried by a traffic fine. But when Lady Eliza Manners was caught speeding, she avoided paying off the full £100 ticket by claiming ‘financial hardship’. And apparently she’s not the only budget-conscious occupant of the Leicestershire property. Her mother Emma, the Duchess of Rutland, recently claimed she shops in Asda.

While it might be hard for those on the actual breadline to sympathise with the troubles of the titled and entitled, such states of affairs do stand to some sort of reason. If you think heating your two-bed home has become an expensive business, try being Julie Montagu, Viscountess Hinchingbrooke, whose electricity bill at Mapperton House in Dorset has tripled in the past 12 months to hit £45,000 a year. ‘I can’t put into words how much work is involved in maintaining these historic houses,’ Montagu, who has blisters all over her hands, tells me. ‘Weekends just don’t exist for me. When things break you have to replace them like-for-like, and there’s usually only about two people in the country able to help.’

This is not an uncommon problem. Because in lots of instances, having a vast via-the-bloodline property does not also mean access to a bottomless pit of cash. James Probert of Historic Houses says that between his organisation’s 1,500 members there’s a £2 billion repair and maintenance backlog.

‘I did it out of curiosity, triggered by things like Downton Abbey, and Madonna’s wedding in a castle’

So what are all these impoverished castle owners to do? Many are wisely capitalising on North America’s great obsession with the English aristocracy. The Duchess of Rutland has set up an organisation specifically to cipher money out of the US and into her castle: American Friends of Belvoir Castle. Each ‘friend’ parts with $2,000 for the privilege of joining. Next year she’ll be hosting a gala at The Breakers in Palm Beach to raise even more funds.

Belvoir is far from the only castle being sustained by the dollar. The Earl of Carnarvon, George Herbert, who lives in Highclere Castle (best known as Downton Abbey) tells me he would struggle without all his American visitors and their generosity in the gift shop. Even with the American support, though, castle living is far from a fairytale. ‘There’s never a day when there’s not something being fixed somewhere,’ he sighs. ‘We’ve had quite a struggle over the years.’

Montagu – an American herself – helps prop up Mapperton with a YouTube channel focused on its history. It’s pulled in 166,000 subscribers, 70 per cent of whom are American. She also has a GoFundMe page to raise funds to replace a £10,000 broken lead eagle – many donations for which have come from American supporters.

With all this in mind, poor stately home and castle owners could be forgiven for wanting to sell up, buy a three-bed flat in Fulham and spend the freed-up cash on gilets and Annabel’s membership. And those selling up can often count on American interest.

Director of Savills’s country house department Edward Sugden, who has just flogged a £25 million property in the Cotswolds, says Americans are jumping on the opportunity to invest in high-end UK property as the pound continues to look weak against the dollar. Tim Dansie, a director at Jackson-Stops, tells me: ‘American buyers seem to start in London which they know and then move to the Cotswolds, which they also know. The west of London seems to be slightly trendier.’

The question is, why do Americans want to part with their cash and take on such a burden just for a slice of British heritage? Especially given one of their number recently made a Netflix six-parter about the horrors of living like a princess in the pokey grounds of Frogmore Cottage.

Well, there’s a saying that the difference between America and England is that Americans think 100 years is a long time, while the English think 100 miles is a long way. And this seems to speak to the American attitude to English properties. Mark McAndrew, head of Strutt and Parker’s estate department, says his American buyers are almost always fascinated by the history of a property and rarely mind having to drive a couple of hours from London. No wonder then that last week estate agents felt able to put Buckinghamshire stately home Denham Place, which was used for James Bond scenes, on the market at £75 million. The owner says they’re expecting Americans to take a great interest.

American Ann Kaplan, who lived in Las Vegas for ten years (but is famous for starring in Real Housewives of Toronto), started looking into castles after living in London for a few years. ‘We have many residences but I was blown away by the cost of living in London,’ she says. ‘I thought: “If an apartment is £8-£9 million I wonder what a castle costs?” It was out of curiosity, triggered by things like Downton Abbey, and Madonna’s wedding in a castle.’ It turned out, for Kaplan, they were comparatively cheap. So, this year, she bought Lympne Castle in Kent for around £11 million.

While Americans might have a great fondness for Britain’s aristocracy, the feeling is not always mutual. Montagu, who was a self-proclaimed ‘all-American, former captain of the cheer squad’, tells me some members of the aristocracy shuddered at the thought of her moving in. ‘There is still that snobbery or that wishing it could be the way it used to be,’ she says. ‘I was championing Meghan when she married into the family and thought it was great for us handful of Americans who had married into the aristocracy. Obviously that hasn’t gone very well so I can’t look to Meghan like: see, she’s made it.’

Americans are jumping on the opportunity to invest in high-end UK property as the pound continues to look weak against the dollar

When Kaplan bought her castle this year she received comments too nasty to relay here. But does it really matter who the properties most closely associated with British history are actually occupied by? Won’t people still want to come to see them no matter what? If the King, for example, found himself in financial hardship, facing one leaky roof too many and sold his country piles to an American, would tourists still flock to Balmoral or Sandringham? Of course they would.

In truth, there’s also a case to be made that Americans make for far better custodians of British heritage. In contrast to the not insignificant number of Brits who have become rather disparaging about our history, those from across the pond have greater reverence for it – and if they’ve got the money to pour into keeping these ancient properties up and running, why shouldn’t we welcome them?

The reinvention of Jude Law

The late director Anthony Minghella made three films with actor Jude Law: The Talented Mr Ripley, Cold Mountain and Breaking and Entering. They would undoubtedly have made more if Minghella hadn’t died at the cruelly young age of 54 in 2008. He referred to the actor as ‘my muse’, but had a more perceptive comment about him too. ‘Jude is a beautiful boy with the mind of a man. A true character actor struggling to get out of a beautiful body.’

For years, Law seemed to struggle with the weight of his good looks, taking on mediocre roles that talent agencies and producers had shoehorned him into. Now, at the age of 50, he has embraced middle age and the greater opportunities for versatility it offers. He is a true character actor in a handsome, rather than beautiful, man’s body, and one of the most exciting – and unpredictable – thespians working today.

Law’s latest performance, as Captain Hook in David Lowery’s new Peter Pan and Wendy, offers ample proof of his talent and versatility. The role of Hook is often an actor’s graveyard, condemning the likes of Jason Isaacs and Dustin Hoffman to overblown buffoonery. But Law imbues what can be a stock villain with both poignancy and menace, even as he sports a ratty moustache and hideous, straggly hair. Lowery’s film is hardly the animated Peter Pan, but amid its quirkiness and revisionism, Law’s performance stands out for both its eccentricity and commitment. Twenty-four years ago, he was a golden, loathsome Dickie Greenleaf in Ripley; now, he’s a different kind of plunderer altogether, but remains as scene-stealingly excellent as he ever was.

For years, Law seemed to struggle with the weight of his good looks, being shoehorned into mediocre roles. Now, at 50, he has embraced middle age and the greater opportunities for versatility it offers

It seems bizarre to recall that there was a time when Law was so ubiquitous, often in undistinguished films, that Chris Rock mercilessly mocked him at the 2005 Oscars. The comedian jeered: ‘You want Tom Cruise and all you can get is Jude Law? Who is Jude Law? Why is he in every movie I have seen the last four years? He’s in everything.’ The actor later commented: ‘At first I laughed, because I didn’t think he knew who I was. Then I got angry as his remarks, I felt, became more personal. My friends were livid.’ One of those friends, Sean Penn, solemnly pronounced at the ceremony: ‘Jude is one of our finest actors.’ But the sense of Law’s star being in eclipse did not leave him for years. Then he stopped being a leading man, embraced his destiny as a character actor and had a great deal more fun.

He played Dr Watson in Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes and its sequel, and was an effectively chilly Karenin in Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina. He also appeared in the final Hollywood film made by pre-disgrace Woody Allen, A Rainy Day in New York. Law, who has kept his personal and political views largely to himself, save for his outspoken support for the Peace One Day movement, remarked that it was a ‘terrible shame’ that its release was cancelled, even as his co-stars handed their fees back as a sign of protest at Allen’s notoriety. Something, of course, they could not possibly have known when they signed up for the film.

Law’s personal life has been well documented by the tabloid press, and the financial demands of his seven children have presumably necessitated his appearing in numerous big-budget franchises and sequels, from the ill-fated Fantastic Beasts pictures to his taking Marvel and Star Wars dollars. It would be unsurprising to see him appear in the next James Bond film as M, following in the footsteps of Ralph Fiennes – another Minghella leading man turned peerless character actor. Yet he’s also capable of subtle and surprising work, whether on stage – he made a fine, pensive Hamlet – or on film, as in the credit crunch black comedy The Nest. He’s about to play Henry VIII in Firebrand, opposite Alicia Vikander’s Catherine Parr.

The man’s mind that Minghella praised is a versatile and playful one, and whether he’s Captain Hook, Dumbledore or a despotic king, he’s one of the most interesting actors working today. Somehow, you can’t imagine any more Chris Rock jokes being cracked about him in the future.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s World edition.

Questions raised over SNP police raid timing

It’s not the SNP’s year is it? Just when the nationalists thought they could catch a break after the chaos of recent months, fresh revelations have been published about the infamous police raid on Nicola Sturgeon’s house. It turns out that Police Scotland put in their requests for a search warrant of the Sturgeon-Murrell property midway through the leadership contest on 20 March. But officers were left waiting for another two weeks until they got the green light on 3 April — seven days after the contest had ended.

Talk about convenient timing for establishment candidate Humza Yousaf. Had those scenes of the blue forensic tent been engrained in voters’ minds during the race, the election — which Yousaf narrowly won on second preference votes — could well have had a very different outcome. Of course, the Crown Office – presided over by a Scottish government minister – denies that any operations were delayed due to the leadership contest. But one police source has told the Scottish Sun that where operations could cause ‘huge political ramifications’ then ‘this would be taken into consideration’.

Scottish Labour’s deputy leader Jackie Baillie told the paper that ‘this is a very interesting revelation that will lead to raised eyebrows across Scotland.’ That’s putting it mildly Jackie…

Prigozhin’s ‘treachery’ poses a dangerous challenge to Putin

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the businessman behind the Wagner mercenary army, likes accusing his political enemies of ‘treason’ for not backing him as much as he’d like. Now, though, he appears to have committed that very crime himself – with the revelation that US intelligence reports suggested he tried to cut a deal with HUR, Ukrainian military intelligence.

These reports were part of the trove of classified materials leaked onto the Discord gaming server earlier this year. Taken on their own, they could be regarded as sneaky fakes intended to undermine Prigozhin, yet many other documents within the collection have quietly been acknowledged as real. While it still cannot be taken as wholly proven, in Russia even some of Prigozhin’s erstwhile supporters are accepting their veracity.

Indeed, when Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky was asked about the claims during an interview with the Washington Post, he responded with a prickly defensiveness. This did little to dispel belief in either the Prigozhin claims, or separate US reports that suggested Zelensky himself had raised the prospect of cross-border incursions into Russia – something he has denied in public.

This is an example of the way that Putin’s style of managing the elite has proven dangerously dysfunctional

According to the reports, Kyrylo Budanov, head of HUR, warned Prigozhin that a Russian plot to destabilise Moldova involving former Wagner fighters was intended to incriminate him, precisely because he already had dealings with HUR. These were apparently arranged in Africa, where Wagner has extensive interests, and led to Prigozhin making an extraordinary offer in January: in return for the contested city of Bakhmut, he would supply Kyiv insider intelligence on the location and disposition of regular Russian military units and ammunition stocks. He even encouraged Kyiv to launch an attack on Crimea.

That Prigozhin is a thuggish opportunist willing to throw anyone under a bus when it suits him is hardly news. However, if the reports are to be believed, it would suggest that his desperation to deliver Vladimir Putin a victory at Bakhmut, as well as his vendetta against Russia’s defence minister Sergei Shoigu, pushed him to foolhardy lengths. As it was, the Ukrainians rejected the offer, suspecting double-dealing.

If it were a ruse, though, one might expect Prigozhin to say so, now that it has become public. Instead, he dismissed it as a laughable smear dreamed up by ‘people from Rublyovka’ – an exclusive Moscow suburb, home of many of the elite – to undermine him, adding that ‘reading this is of course nice,’ because it implied ‘Zelensky is also obeying my orders.’

This is an example of the way that Putin’s style of managing the elite has proven dangerously dysfunctional when transplanted to the battlefield. A culture of mutual suspicion, cannibalistic competition and opportunistic self-interest has kept Putin in power for more than two decades. It has allowed him to play individuals and interests against each other and forced the members of his court constantly to seek his ear and favour. In war, though, the need is for unity, discipline and mutual support – something the Ukrainians are displaying and the Russians clearly lack.

Prigozhin appears to be willing to see the Russian invasion falter, so long as Wagner could shine. This treachery – because it is hard to characterise it as anything else – may seem extraordinary (and it is extraordinarily foolish), but it is no more than a particularly extreme by-product of Putin’s system.

It poses an acute challenge for the president. For all his macho public persona, Putin is not a man who takes difficult decisions easily or quickly, and he is clearly uncomfortable with any major reshuffles at the top of his security structures. He may be tempted to try and ignore these revelations in the name of not disrupting Wagner at a time when it is still at the forefront of the battle for Bakhmut and with the Ukrainian counter-offensive looming, or simply give Prigozhin a symbolic slap on the wrists.

If he does that, though, he will show himself as weak. At a time when so many within the elite are wondering for all kinds of reasons whether Putin is still the man Russia needs, any such missteps make it more likely that when he is faced with some true systemic crisis, they will decide he neither deserves their support, nor is dangerous enough to compel it.

Scotland’s NHS is facing a retention crisis

Junior doctors in Scotland want change. They want better pay, kinder working conditions and for the Scottish government to take their demands for full pay restoration of just under 35 per cent seriously. Otherwise, they say, they’ll simply up and leave to greener pastures – or hotter beaches, as the exodus to Australia continues.

It was revealed last week that 97 per cent of those medics who had voted in the BMA strike ballot cast their votes in favour of industrial action. The turnout was high at 71 per cent but could have been higher still, as it is understood that Civica, the external organisation in charge of posting ballot papers, ran into problems meaning an as yet unquantified number of medics never received their voting cards.

While the BMA has been criticised for choosing to focus entirely on pay as the sole negotiating ground in these disputes, the bigger picture should not be overlooked: the toll that poor working conditions is having on NHS workers is significant. Just under 75,000 NHS staff have taken time off work in the last five years due to mental health-related illnesses, as revealed by a freedom of information request made by the Scottish Conservatives. Burnout is increasing amongst doctors UK-wide: in 2022, 39 per cent of junior doctors said they had experienced burnout to a high or very high degree due to the work – an increase of six per cent on the previous year.

Healthcare providers in Australia have no qualms about capitalising on the dissatisfaction of medics here using emails and adverts to entice junior doctors over.

In Scotland, 44 per cent of junior doctors surveyed by the BMA have actively researched leaving the NHS in the last 12 months. A trend is emerging: once doctors have finished their foundation programme – the initial two years of training medics have to complete in the UK after graduating – many turn their attention to sourcing locum work or long-term specialty training jobs overseas.

‘Australia offers more favourable working conditions,’ one foundation year medic planning to move abroad told me. ‘Junior doctors in the NHS are made to feel as if they can only begin to plug gaps in an underfunded system, whereas Australia offers junior doctors a chance to professionally develop themselves in a system where they are valued. The fact that well over half of the doctors I know are moving across the world tells its own story.’

And healthcare providers in Australia have no qualms about capitalising on the dissatisfaction of medics here: using emails and adverts to entice junior doctors over. Dr Sophie Nicholls, a UK-based sexual health doctor, said online: ‘I have daily emails from Australia with tempting offers. Our doctors will move with their feet if they are not recognised for the work they do and paid appropriately.’

Doctor-turned-comedian Dr Adam Kay recently shared a picture of an advert placed in the British Medical Journal by Blugibbon Medical Recruitment. ‘Got that Dr Adam K feeling? Come to Australia!’ the jolly bubble font cried. ‘Work 10 x shifts per month & travel, swim and surf in the sun for 20 x days! $240,000 annual salary package. Accommodation provided. $5,000 sign-on bonus for 12 months of commitment.’

You can’t say it’s not tempting. Dr Kay hinted at the ‘big question’ facing both the UK and Scottish governments: ‘If you don’t address doctors’ very reasonable pay concerns, alongside their conditions and wellbeing, guess where they’re going?’

Scotland has so far avoided healthcare worker strikes, which First Minister Humza Yousaf points to as one of his few successes as health secretary. The impression amongst junior doctors north of the border is that the Scottish government is more serious than Westminster about their demands. Scotland’s health secretary Michael Matheson has already met with the doctors’ union last Thursday, though it’s currently unclear how the negotiations are proceeding. How much will the Scottish government be prepared to offer junior doctors? Matheson refused to commit to a figure, saying only that ‘negotiations to agree a pay uplift are already underway’.

Dodging strike action is only a short-term goal, of course; long term, the real problem remains: how to make sure more doctors are trained in the UK – and that they stay here. During his leadership campaign, Yousaf described the Scottish government’s ‘three pronged strategy’: to increase medical graduates by 100 per year, to recruit domestically and to recruit internationally. But Scotland sees approximately 700 doctors leave the country to work elsewhere each year and in 2016, a fifth of doctors finishing their foundation programme in Scotland left to find better jobs elsewhere – some for England, and some for much further afield.

‘We’ve got to make sure we’re not filling up a leaky bucket,’ Yousaf admitted to me outside a Dundee GP practice during the leadership contest. While the former health secretary said he wouldn’t give medics the full pay restoration they were looking for, he accepted that the system for junior doctor allocation to hospitals post-graduation could be examined ‘so we don’t spend years and years training somebody up only to lose them because we’re being inflexible’.

So how to stop the exodus? Scottish Labour’s deputy leader and health spokesperson, Jackie Baillie, said that she was ‘not adverse’ to considering options that would see Scotland-trained medics obliged to work in the country’s NHS for a certain number of years after qualifying. ‘Do I think if we’ve spent hundreds of thousands of pounds training a junior doctor – which we have – that we should expect some longevity of service to the NHS? I think that’s perfectly reasonable.’ But Baillie makes clear that this wouldn’t be a policy introduced without movement on pay: ‘You can only apply the golden handcuffs if you are fair about the pay that you give people. I would want to talk to the BMA, and to junior doctors, about how we land this in the best possible way. I don’t want anything we do to accelerate people leaving.’

A common thread unites the Scottish political parties across the divide on the junior doctor issue: firstly, that some sort of pay rise is needed (though no one wants to be the first to name their price), and secondly, that the workforce crisis cannot be solved by wage increases alone. Baillie discussed rota complaints, missed breaks and unpaid – and often unplanned – overtime as being key areas to sort out, while Dr Sandesh Ghulane, the health spokesperson for the Scottish Conservatives, pointed to ‘the little things’ that need changed, like food provision for those working night shifts and better rota organisation. Free accommodation offered by hospitals – an incentive offered in the above advert from Australia – is another concession that could help relieve pressures from medics, Ghulane suggested.

‘Do I think if we’ve spent thousands of pounds training a junior doctor that we should expect some longevity of service to the NHS? I think that’s perfectly reasonable,’ said Scottish Labour health spokesperson Jackie Baillie.

Another problem is managing the expectations of BMA members: while some medics in Scotland have admitted that they would accept a pay rise of less than 35 per cent (with others admitting that it was their work-life balance rather than their pay checks that most concerned them) there are groups of members within the doctors’ union who remain vocal in their demands to accept nothing short of full pay restoration (FPR).

‘As unrealistic as it may seem, I really hope the BMA remains strong for genuine FPR,’ one junior doctor wrote. ‘It’s honestly the bare minimum needed to keep us going in the NHS. It’s just not a viable career anymore in the UK.’ Agreeing, another medic responded: ‘Frankly, if we were to get an offer close to but not quite FPR and the BMA asked us to vote on it, I would personally vote no. It’s unaffordable to be a doctor in the UK and we have the ability to work for better pay and less hours elsewhere.’

Health secretary Michael Matheson says he has been frank in negotiations so far and remains firm that ‘the recruitment issues are not all about pay’. Perhaps aware that this line of discussion may not fly with the BMA, Matheson has also revealed that he’s already asked NHS boards to start preparing contingency plans should the strikes go ahead.