Get ready for Boris vs the Bank of England

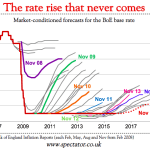

Westminster is, naturally, fixated on Boris Johnson and his first speech since his Conservative leadership victory. But it’s just possible that the most interesting and important speech of the day took place in Scunthorpe. That’s where Andy Haldane, chief economist of the Bank of England was delivering a speech called ‘Climbing the Jobs Ladder’. His speech was, nominally, about wage progression and the quality of employment. But about halfway through, the speech becomes something very different, something that looks an awful lot like a warning to a new prime minister: don’t bank on the Bank to bail you out over Brexit. Haldane’s argument is that the major downside risks to