On the offensive

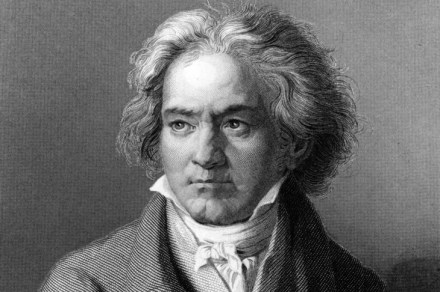

‘I’m an amateur,’ Barry Humphries tells me. The Australian polymath uses the word in its older sense of ‘enthusiast’ rather than ‘bungler’ and he feels no need to point out the distinction. He’s in London to perform a three-week residency at the Barbican — Barry Humphries’ Weimar Cabaret — with his fellow Australian Melissa Madden Gray, who uses the stage name Meow Meow. The show was inspired by Humphries’ fascination with Germany’s culture during the interwar years. ‘It was the last song before the nation slid into moral squalor. And I have a long-standing interest — I won’t say “passion” because one gets “passionate” about deodorants — but I have