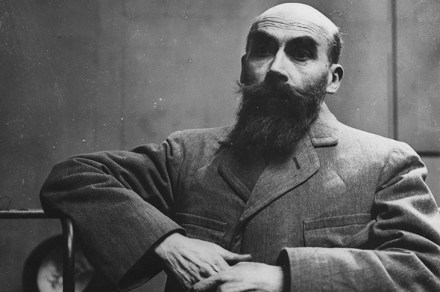

A moral hypochondriac

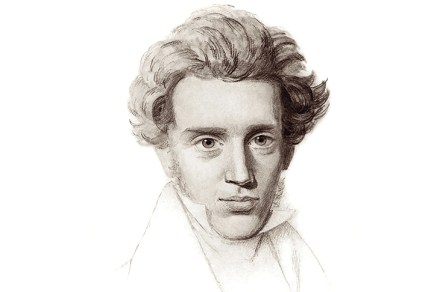

Surely God, if He existed, would find a major source of entertainment down the ages in the activities of theologians, reaching their climax perhaps in the 19th century, when they involved Him with German idealism, and then the descent from that to the present day, when the sheer naivete of anyone who thinks that God is ‘out there’ or actually exists, in some sense we can understand, provokes genial and condescending ridicule from the professionals. Central to the development of thought about Christianity is the work of the melancholy Dane Søren Kierkegaard, who in the course of his short life — he died, aged 42, in 1855 — wrote more