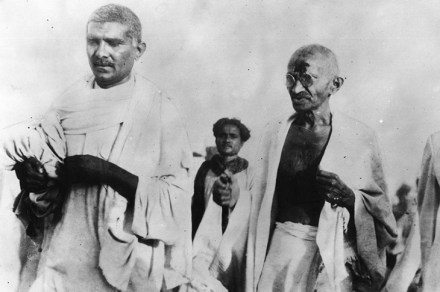

The scourge of the Raj

‘It’s a beautiful world if it wasn’t for Gandhi who is really a perfect nuisance,’ Lord Willingdon, Viceroy of India, wrote in 1933. Gandhi would have been 150 years old in 2019, had he taken better care of himself. He remains the most irritating and admired politician of the 20th century: a perfect subverter of power and political logic, but a nuisance to everyone, allies included. Only Hitler, the other anti-capitalist spiritual politician who broke the British Empire, fascinates to the same degree. The first volume of Ramachandra Guha’s biography, Gandhi Before India (2013), carried the young Gandhi across the British Empire from Kathiawar to London to Cape Town. In