Four German-speaking philosophers in search of a theme

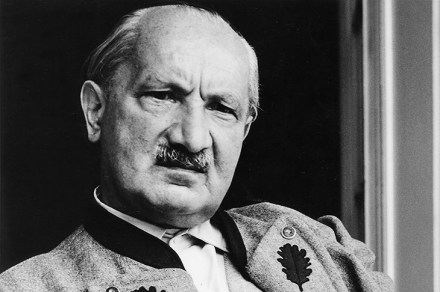

How do you write a group biography of people who never actually formed a group? Such is the challenge Wolfram Eilenberger sets himself in a book about the philosophers Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Walter Benjamin and — the surprisingly unstarry fourth subject — Ernst Cassirer, an urbane and now nearly forgotten neo-Kantian who might have deserved the made-up title of ‘symbologist’, thus far reserved for the heroes of Dan Brown’s novels. What these men have in common is that they spoke German and were philosophically active during the 1920s, but that is about it. Heidegger and Cassirer met and traded rhetorical blows at a celebrated philosophy conference in Davos; Benjamin