Another drama about how women are great and men are rubbish: C4’s Philharmonia reviewed

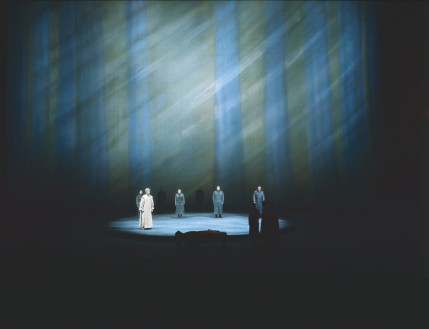

On the face of it, a French-language drama about a Parisian symphony orchestra mightn’t sound like the most action-packed of TV watches. In fact, though, Philharmonia (Sundays) is pretty much Dallas with violins. The first episode began with the eponymous orchestra blasting out a spot of what Shazam assured me was Dvorak, before its elderly conductor dropped his baton and collapsed to the floor, never to rise again. Cue a pair of Gallically elegant female lower legs making their way through the airport as one Hélène Barizet arrived from New York to take over the role. David was left in a tartan bag in Belfast; Helen was discovered in a