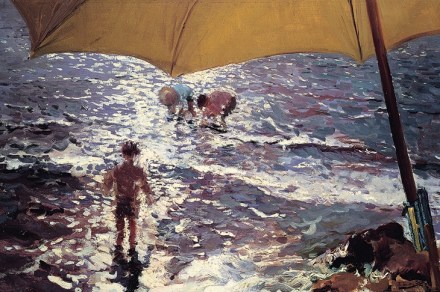

Modern sublime

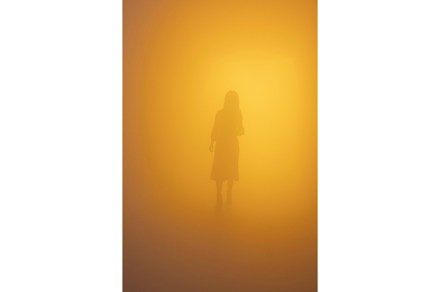

Superficially, the Olafur Eliasson exhibition at Tate Modern can seem like a theme park. To enter many of the exhibits, you have to queue. The average age of the crowds in the galleries is much lower than it might be at, say, the RA. And most visitors keep their phones permanently ready to snap a selfie — which isn’t really what the artist has in mind. He wants you to concentrate on a reaction that is internal and unphotographable. Eliasson — as the title of the show, In real life, might suggest — offers sensory experiences. One of the most memorable of these is produced by ‘Din blinde passager’ (‘Your