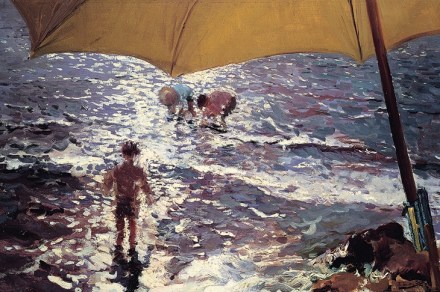

Master of white

Artists can be trained, but they are formed by their earliest impressions: a child of five may not be able to draw like a master but he can see better and more intensely. The light of Valencia was burnt into Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida’s mental retina and he could not get it out of his mind: ‘I live here like an orange tree surrounded by heaters,’ he told an interviewer in Madrid in 1913. Never a studio painter, he worked best under the lamp of his native sun and returned to Valencia from wherever he was living every summer to set up his easel on the beach. His ambition was