The Christmas when Parisians ate the zoo

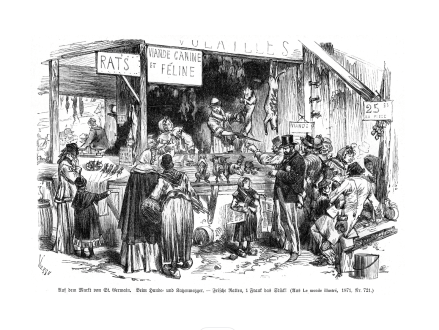

Even if you don’t like Christmas, it’s hard to deny that Christmas dinner is one of the best meals of the year. But for Parisians in 1870, the Christmas meal took an unexpected and macabre turn. While we may think of Paris as being the city of light, good food and fine wine, it’s also the city that once produced a Christmas Day menu of stuffed donkey head, elephant consommé and roasted camel – all courtesy of the Jardin des Plantes zoo. In the late stages of the Franco-Prussian war, Paris found itself surrounded by enemy forces. The Germans aligned themselves with Prussia with a plan to bombard and starve