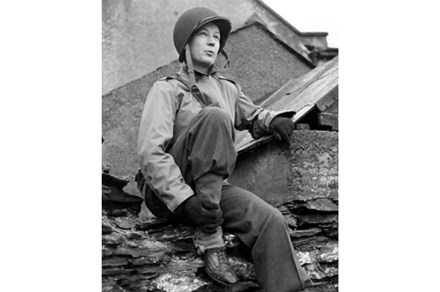

Out-scooping the men: six women reporters of the second world war

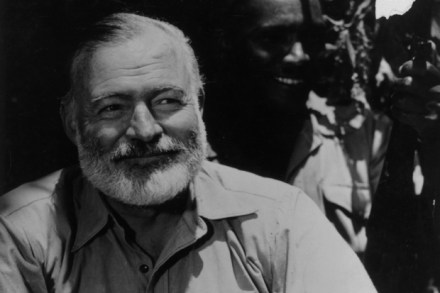

Two war correspondents were hitching a lift towards Paris in August 1944 when a sudden wave of German bombers forced them to dive for cover. What the hell were they doing trying to cadge a ride when ‘war correspondents have their own jeeps and drivers?’ an American officer barked at them as his car screeched to a halt beside the shallow crater they had commandeered. ‘We happen to be women,’ Ruth Cowan replied steadily, as she straightened up and shook off the dust along with his words. Cowan was the first female journalist attached to the US army but, as a woman, she was denied the official facilities provided for