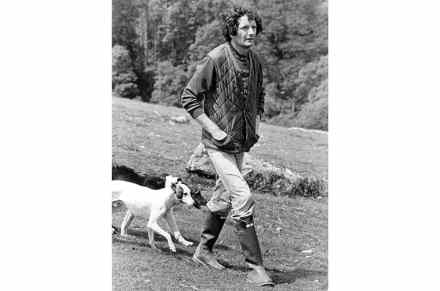

Norman Scott has the last word on a very English scandal

I’m glad Norman Scott can say he has ‘always had the ability to laugh at the absurdity’ of his existence because, as detailed here in a long-awaited memoir, I too couldn’t stop shrieking, he is so tragic. When he came home unexpectedly as a youngster, for example, and witnessed his mother having sex in the lounge with a telephone engineer, he was so shocked he dropped his tortoise. ‘The terrible guilt over my tortoise stayed with me,’ he writes – maybe until just the other day. Scott is now 82. He’ll always be remembered of course for the Jeremy Thorpe trial, when the judge, Mr Justice Cantley, called him a