Hitting the high notes

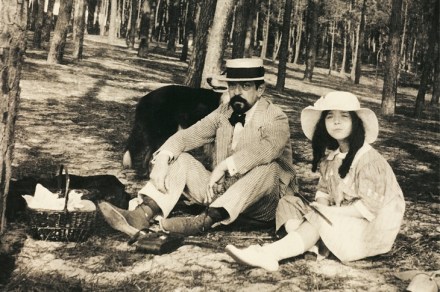

Claude Debussy died on 25 March 1918 to the sound of explosions. Four days earlier, the Kaiser’s army had deployed its long-range Paris Gun, and as Debussy’s cancer entered its final hours, artillery shells were bursting in the streets around his home in Avenue du Bois-de-Boulogne. This quiet modernist — who’d transformed music into an art of almost limitless expressive subtlety — died amid the thunder of mechanised war. The funeral was poorly attended, and as the cortège halted, curious shopkeepers glanced at the wreaths: ‘It seems he was a musician.’ The classical music world is morbidly addicted to anniversaries of major composers. It’s still unclear whether the listening public