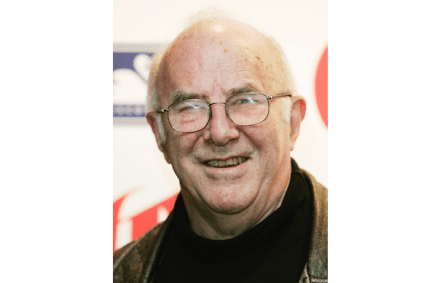

Books Podcast: Wendy Cope

In this week’s Books podcast, I’m joined by the great Wendy Cope, whose new collection Anecdotal Evidence is just out. I talk to her about why she’s funniest when she’s most serious, the fascination of writing in form, the disappearance of Jake Strugnell, the recent row over whether the spoken-word work of Hollie McNish and Kate Tempest counts as “real poetry”, and get the scoop on her second-worst marital row ever — plus, she reads some poems from her new book. You can listen to our conversation here: And do subscribe on iTunes for more like this.