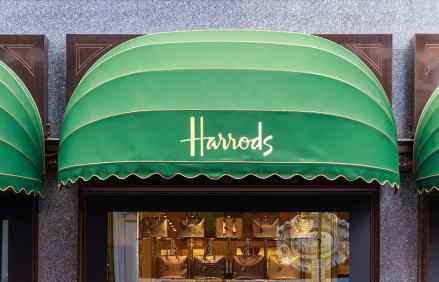

The secrets of London by postcode: W (West)

It’s the area that unites James Bond, Rick Wakeman and both Queen Elizabeths. In the first of our series looking at the quirky history and fascinating trivia of London’s postcode areas, we explore the delights to be found in W (West) – everything from fake houses to shaky newsreaders to dukes who are women… Answer: the other Tube station whose name contains all five vowels is Mansion House.