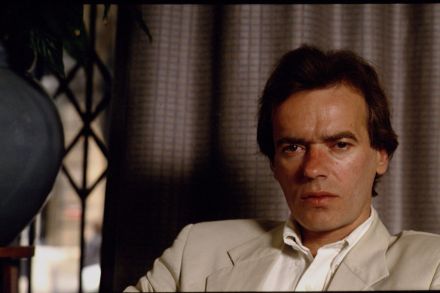

Martin Amis: 1949-2023

Over the next few days, people will be reaching for certain set phrases about Martin Amis. That he was ‘era-defining’ (though he defined more than one era); that he was ‘genre-defying’ (he defied more than one genre); that he was an ‘enfant terrible’ (it will be wryly noted that he remained an enfant terrible, somehow, into his eighth decade). It’s poignant, I think, that a writer who vigilantly waged the career-long battle he called ‘the war against cliché’ will go to his grave heaped with the garlands of the old enemy. Still, he deserves the content of those tributes if not their form. And it’s not much of a surprise that nobody can write as well