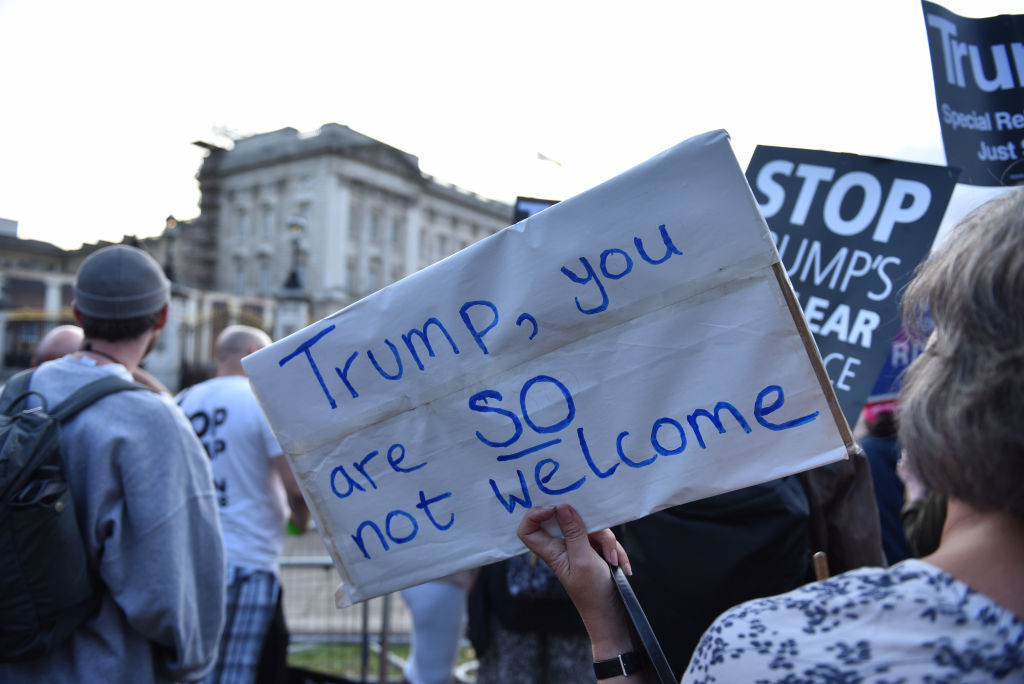

American politics – like our own – is more polarised than ever. More than perhaps any other president in living memory, Donald Trump has divided opinion. To his supporters, he can do no wrong. None of the old political orthodoxies seem to apply. To his detractors at home and abroad, his presidency is an embarrassment, arousing expressions of hatred rarely seen in Western politics.

But we would be foolish to muddle a dislike of a particular President with our historic and deep commitment to an enduring, strong, British-American relationship. Even more foolish to presume that everything he says or does has no merit. This week we will commemorate our shared sacrifices in the D-Day landings, but I will also be thinking of Monte Cassino where my father fought as part of the British Eighth Army – alongside the American 5th Army and alongside our brave Polish and other allies – with 55,000 Allied casualties; and I will also be thinking of the extraordinary generosity which led to the Marshall Aid Programme (worth over $125 billion in 2019 US dollars) to help rebuild Western European economies and democracies after the end of World War II.Those who protest against President Trump this week too easily forget where our true friendships lie.

Fevered anti-Americanism is an especially grave error in the context of the rise of an increasingly aggressive China. And calling out the nature of Chinese Communism is not the personal preserve of the President. There is only one area where there is near unanimity in Washington DC: China policy. From Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi in the Democrats to Marco Rubio and Mike Pence in the Republicans, China is a unifying issue in American politics today. Trump’s China stance is not seen to be eccentric or extreme in Washington, it is the new American mainstream. And with good reason. American concerns about China rightly recognise both their grievous human rights record at home, and the threat they pose to the international rules-based order. We must not underestimate the serious dangers posed by China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour on the world stage combined with its increasingly repressive behaviour towards its own people. Under Xi Jinping, we have seen a rapid and significant deterioration in political rights, in freedom of religion or belief and in freedom of expression. The Chinese Communist Party routinely use harassment, intimidation, arbitrary detention, torture and imprisonment. Thousands of lawyers, journalists, academics, labour activists and students have been targeted in this way. From the treatment of house church Christians to adherents of the Falun Gong spiritual practices, religious adherents are particularly vulnerable. The most grotesque abuse of human rights is the mass detention of over one million people in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Normal life for Muslims has become impossible. How does this differ from the Siberian gulags experienced by Solzhenitsyn or the treatment of Soviet dissidents like Academician Sakharov? One of the places where the situation is deteriorating most rapidly is in Hong Kong. Over the weekend there were news reports that Germany has given political asylum to two of Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigners. That tells you all you need to know about the emasculation of Hong Kong’s basic freedoms. Despite promises in the handover agreement that rights will remain intact in Hong Kong, freedom of the press, the rule of law, and freedom of expression are being rapidly whittled away. Proposals to change the city’s extradition law have been described as a ‘legalised kidnapping’ law which will allow the Hong Kong government to extradite political opponents or business leaders to mainland China where forced confession is routine. This is a clear breach of the handover agreement and carries an important lesson at this time: the Chinese Communist Party cannot be trusted to keep its promises, even when they are written in international law, and they do not share our core values. So if we come to a choice between allying with America, where rule of law, human rights and democracy remain core values, or China, where the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre have been airbrushed out of China’s history, there should be no contest. We should be wary of compromising our natural alliances because of fear of commercial repercussions from Beijing over issues such as the incorporation of Huawei technology into British infrastructure. China does not share our values, and we should be extremely wary of giving them control of technology and energy and simultaneously jeopardising our core friendships. Instead, we should be willing to call out the abuses of human rights and to stand with our American allies in speaking for the oppressed people of China as we did against the Nazis and Soviets. Carrie Gracie, the former China editor at the BBC, recently told a House of Lords Select committee that it was, “very important to speak up for one’s values, assert where one’s red lines are and be firm about adhering to them, because one’s Chinese counterpart expects that”. We can learn from our American counterparts in doing this. British citizens are among the many families whose relatives have disappeared into Xinjiang’s camps. But where have been our protests? If the UK is to remain committed to its values, we must stand up with the United States to speak up about the appalling situation in Xinjiang. A similarly robust response should be issued by the British government when the human rights situation in Hong Kong worsens. If we fail to act, we not only abandon the victims of grievous rights violations, we may jeopardise our most important alliance. Whatever you think of President Trump, that price is not worth paying.

Comments