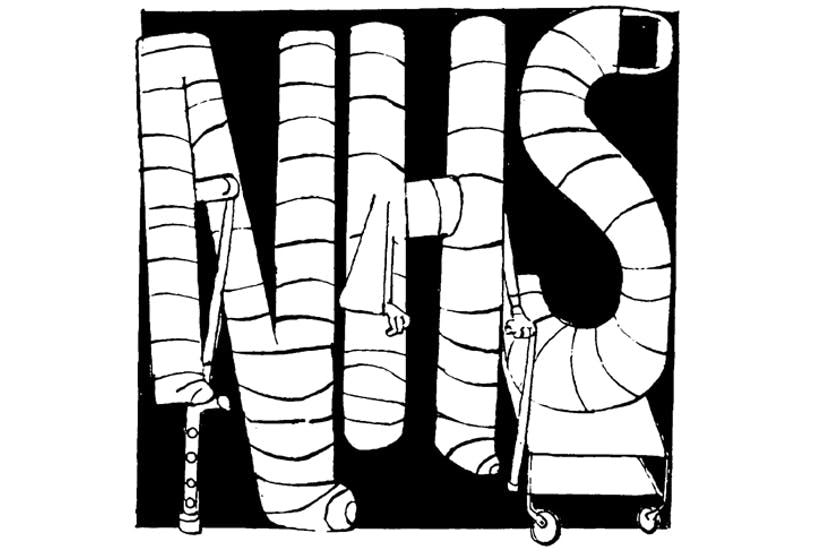

Seventy years ago, when the National Health Service was founded, the UK established the principle of universal access to healthcare. Rich or poor, young or old, you have the right to obtain treatment for your condition. It set a standard amongst the rest of the world, that healthcare is a vital part of a safety net that all wealthy countries should strive to provide. In 1948, this was a new and progressive ideology, far ahead of its time. It’s important to be proud of one’s history – but 1948 is long gone.

What exactly is the UK celebrating today? Universal access is no longer a unique feature of British healthcare. Almost every developed country has adopted this as a policy, providing full coverage for their citizens around the world.

With this crucial issue now equalised, healthcare outcomes should be the focus of the discussion. By this measure, the NHS wildly underperforms compared to its European counterparts, ranking in the bottom third of international comparisons for health system performance. The UK is on par with the Czech Republic and Slovenia; it doesn’t come close to countries like Germany, Switzerland, or the Netherlands.

The Institute for Economic Affairs’ latest briefing on healthcare highlights the realities of being treated on the NHS, especially for serious conditions. The findings are difficult to swallow. If British patients with the five most common types of cancer were treated in Germany, instead of on the NHS, more than 12,000 lives would be saved each year. In Belgium, 14,000 more lives would be saved.

It’s a similar picture for stroke survival rates. 4,300 additional British lives would be saved each year if they were treated in Switzerland. Over 5,000 lives would be saved if treated in Germany or Israel.

These are not statistics that can go in one ear and out the other. We’re talking about thousands of unnecessary deaths, thousands of lost lives.

You will not find a comprehensive healthcare study that paints NHS patient outcomes in a flattering light. Even the Commonwealth Fund study – the outlier report which ranked the NHS at the top of the list in 2014 and 2017 – still ranked the NHS second-to-last in the health outcomes category.

The Guardian, when writing up the Commonwealth Fund study in 2014, noted that “the only serious black mark against the NHS was its poor record on keeping people alive.” Maybe I’m missing the point, but it strikes me that when people inquire about the success of a healthcare system, they’re not asking about how fast the printers are running or how long it takes to compile a list. They’re asking about how likely the system is to keep them alive. There’s no denying it: today’s NHS fails patients. Why is this impossible to discuss?

The unadulterated praise for the NHS in the lead-up to its 70th birthday has been completely out of step with reality. Watching BBC2’s ‘NHS at 70’, or following along to the NHS sing-along last night, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the UK is the only place in the world with doctors, hospitals, or access to any form of healthcare treatment. These jolly sing-alongs have a sinister side. Pretending that the NHS is beyond criticism or scrutiny makes it easy to demonise those who stick their head about the parapet and tell it like it is. To even mention the healthcare systems in France, Germany, or the Netherlands is met with accusations of ‘mass privatisation’ or conspiracy theories about the destruction of universal access to care. It is a strange state of affairs, when the many who praise the NHS for providing universal healthcare actively turn a blind eye to the quality of care the system provides.

The birthday celebrations will be over next week, and the NHS will be back to business as usual – that is, dealing with perpetual crises one day after another. It’s time to be honest about the system’s failures, while there is still time to fix things. Looking backwards will not solve the problems in years to come. Reform of the NHS is long overdue, and no amount of balloons or birthday cake can distract from this obvious truth.

Kate Andrews is news editor at the Institute of Economic Affairs

Comments