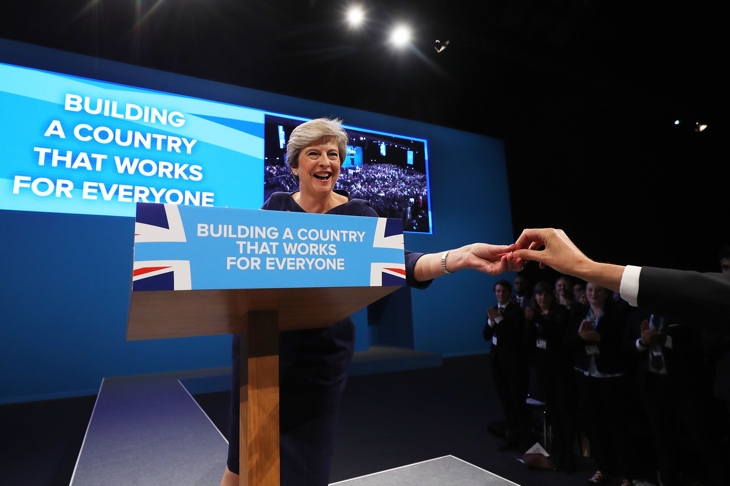

There are many ways to make a conference speech memorable and Theresa May managed most of them. A prankster with a P45, a constant cough and a set that fell to bits as she spoke, the speech was a riot of metaphors in waiting. It may yet be pointed to as a decisive moment in her premiership but it was certainly notable. The only forgettable aspect was the content. When Mrs May tries to inject passion into her voice it is not just the frog that catches in her throat. It is her conservatism.

Conservative politician can ascend to the rhetorical heights at time of peril. Winston Churchill, was, as David Cannadine once wrote, both a master and a slave of the English language. In his early years, Churchill had an unenviable reputation for lavish verbosity. In 1908, as the Colonial Under-Secretary, Churchill gave a speech on an African irrigation scheme in which he tried out a locution that would later become renowned: ‘Nowhere else in the world could so enormous a mass of water be held up by so little masonry’. Churchill was obsessed by speeches. He declaimed his lines constantly, often in the bath. On one occasion his private secretary noted that, lost in the act of composition, Churchill had mistakenly set his smoking jacket alight: ‘You’re on fire, sir,’ he said calmly.

Yet Conservatives do not catch fire often. The history of notable speeches contains many entries by Conservatives but not many pass the test of greatness. Is rhetoric, like comedy, a dramatic art that seems more suited to the dissenters and the radicals than the drier conservatives? There is something in that, to be sure. The anthologies of rhetoric are full of the finest words spoken at moments of great historical change. To the extent that conservatism is a doctrine suspicious of rupture, the relative absence of its advocates from the canon is unsurprising.

Which is not to say that Conservatives have never defined a cause. There has been none greater than the survival of freedom, for which Churchill found his imperishable phrases in the summer of 1940. Mercifully, such moments are rare but attempts to conjure the same spirit have been made in the name of Empire and, in more recent times, Europe. Churchill himself gave the first notable Conservative speech at the University of Zurich in 1946 when he suggested that a continent recently ravaged by war could be healed by a united states of Europe. Not that Britain would do anything so vulgar as actually join, of course. In later years Harold Macmillan, Ted Heath, Geoffrey Howe and David Cameron all gave speeches commending the various guises of the European Union to their party and, at Lancaster House on 17th January 2017, Theresa May read out the last rites of a hostile process that had been started in Bruges, on 20th September 1988, by Margaret Thatcher.

These speeches were all important but none were magnificent. Take Geoffrey Howe’s speech which toppled Mrs Thatcher. With his irrelevant and poorly worked metaphor of the captain breaking the cricket bat, this is one of the worst-written effective speeches in political history. Mrs May’s speech in Florence on 22nd September brings the story of the Conservatives and Europe to an inglorious end and the issue is likely to overwhelm her time in office. It is, for that reason, imperative that the Conservative party finds a rhetorical cause and, though there are not many, the anthologies do contain some exemplars.

William Wilberforce, Conservative MP for Hull, was an eccentric. He was opposed to duels and anxious about the spread of profanity and low salaries for curates. His attempts to ban adultery and Sunday newspapers both came to nothing but, on 12th May 1789, he wrote himself into history with a speech in Parliament on the slave trade. Wilberforce was appalled that British ships were carrying slaves from Africa to be bought and sold in the West Indies as chattels. In response to a Privy Council report on the slave trade, Wilberforce gave a restrained, rigorous but devastating indictment of its moral horror: ‘let us put an end to this inhuman traffic. Let us stop this effusion of human blood’. It took until 1806 for the Foreign Slave Trade Abolition Bill to become law. On that occasion, the Solicitor-General, Sir Samuel Romilly, concluded with an emotional tribute to Wilberforce who was overcome by the compliment and sat, his head in his hands, with tears streaming down his face.

Wilberforce’s methods were always Parliamentary so in that sense Emmeline Pankhurst, the militant suffragette, was an even more unlikely Conservative. Yet one of her finest speeches – ‘The Laws That Men Have Made’ – delivered in London in March 1908, is an authentically conservative case for the franchise. She argued that women ought to have the vote so that their views could be taken into account and the quality of government improved. Throughout Mrs Pankhurst is at pains to suggest that the traditional role of the wife and mother need not be threatened by this venture into politics.

Pankhurst had been born into a radical Manchester family but had become disillusioned with the Liberals. Gladstone showed no interest in votes for women and Asquith was actively hostile. The suffragettes campaigned in by-elections against the Liberals which had the effect of boosting support for the Conservatives. The Labour party Mrs Pankurst regarded as dominated by male trade unionists. There was a typical incident in 1903 when the Independent Labour Party built a hall built in memory of her deceased husband, a radical lawyer active in the women’s cause, but declined to let women enter it. By 1928 Mrs Pankhurst had been selected as the Conservative candidate for Whitechapel and St George’s. Baldwin’s Conservative government duly passed the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928.

The best Conservative blend of rhetorical prowess and practical action, though, is Benjamin Disraeli. The accusation that rhetoric is crafted duplicity never goes away and it was always hard, in Disraeli’s case, to tell which among his many ornate phrases he truly meant. At times the link between Disraeli’s words and the good that got done appeared to be accidental, if not random. That said, his famous One Nation speech at the Free Trade Hall on 3rd April 1872 prefigures almost exactly what his government then enacted between 1874 and 1880. Public health, slum clearance, trade union recognition and improvements to working conditions were all in the speech and action followed on all of them. It is an eloquent reminder that Conservatives can be moved to fine words and that acting to combat injustice is very much the better part of the party’s heritage.

Rhetoric is, in the end, a practical discipline. In an essay on Burke, Hazlitt distinguished rhetoric from both philosophy and poetry: ‘the object of the one is to delight the imagination, that of the other to impel the will’. Rhetoric is designed to make something happen. The opposite of something happening is not conservatism, it is stasis and unless the Conservative party recovers some of the passion of Wilberforce, Pankhurst or Disraeli, stasis is all it will get. Perhaps Mrs May’s inability to speak in Manchester was a distinctive conservative speech after all.

Comments