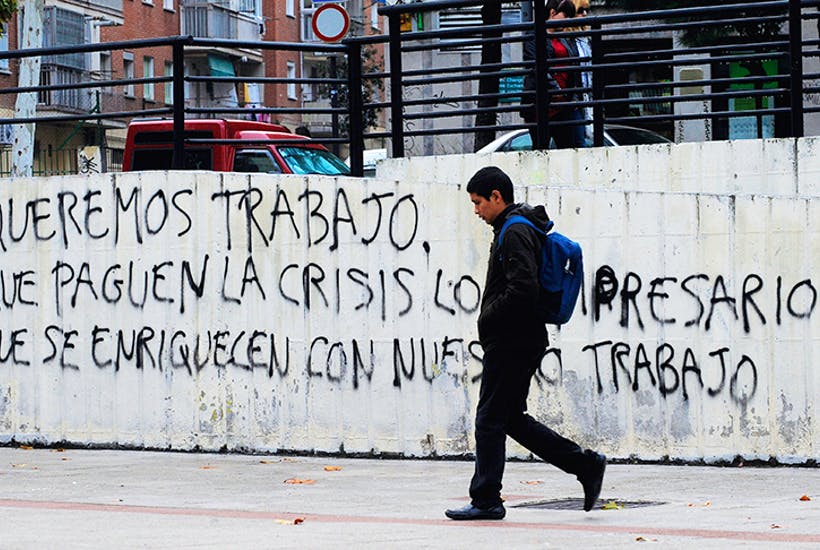

Spain’s recent economic expansion means little to young Spaniards. Many are angry with the country’s tirelessly corrupt politicians, and are unable to pursue rewarding careers in their own country. Despite three-and-a-half years of GDP growth at one of the fastest rates in the eurozone, Spain still has the second highest unemployment rate in the EU, at 18 per cent. More than 40 per cent of Spaniards aged between 16 and 25 are without jobs, while others struggle on temporary contracts with low salaries — or move abroad to find better work.

Does this all mean that Spain suffering is from a ‘lost generation’ of youngsters who are struggling to fulfil their potential? ‘Definitely, and it’s tragic to see,’ says Duncan Wheeler, professor of Spanish Studies at the University of Leeds and author of The Cultural Politics of Spain’s Transition to Democracy. ‘Evidence can be found in the number of Spanish voices heard around many European cities. Some of them are happy to have emigrated; many others aren’t, and have simply been motivated by necessity.’

José Prieto, 24, is from Jaén in Andalusia and recently finished a degree in information technology at Granada University. ‘Spain is a good country to live in,’ he says, ‘but not for working in. The average worker is very undervalued and possibilities for growth in the working environment are practically non-existent.’

José finished his studies this year and plans to seek employment as a computer technician, but his hopes of finding rewarding work in Spain are low. ‘Here computer technicians are no more than people who “work sitting down”, and because sitting requires no effort, we are not considered important. It’s my understanding that in the rest of Europe the working conditions are much better. The work I could do with my degree would be more valued and rewarded outside of Spain.’

Many of those who choose to remain often have to survive on unstable temporary contracts, which guarantee employment only for weeks or sometimes just days. Recent data from Spain’s Ministry of Labour revealed that the number of workers who sign more than ten employment contracts every year increased from 150,000 in 2012 to 270,000 in 2016 — a statistic which also shows where lots of the ruling conservative Popular Party’s much-vaunted 500,000 new jobs a year are coming from.

These contracts, which became increasingly common after prime minister Rajoy’s labour market reforms in 2012, don’t include paid leave or sick pay and offer little protection for workers, who can be fired without explanation or notice. The resulting lack of financial stability has meant that vast numbers of young Spaniards are unable — or unwilling — to move out of their parents’ homes until their late twenties or early thirties. The average age at which Spaniards leave the family home is now 29.

Encar Novillo, 30, is one of the luckier members of a generation who, she says, have been ‘educated or trained to have a good future, but who now don’t see a fair recompense’ for their efforts. At the age of 18, Encar moved out of her family home in Villacañas — a small town in Toledo — to study veterinary science at Complutense University in Madrid. For the last year and a half she has been working as the sole vet in a clinic in a town outside Granada in Andalusia: a region where 58 per cent of Spaniards under 25 don’t have jobs.

‘Living in Spain offers a considerable quality of life regarding the weather and the food for example. But to work in, it’s really disappointing,’ she says. ‘You may be lucky and get a good job, but in most cases you either get a badly paid job or simply can’t find a job.’ Encar works six days a week and, after paying a 21 per cent rate of tax, takes home less than €1,000 a month.

Young Spaniards who have managed to achieve professional satisfaction and financial independence know that many of their generation have not — and perhaps never will — enjoy the same success. Maria Saelices, 29, works for Munich Re, a German re-insurance company, in Madrid. ‘I consider myself lucky to have always been employed and mostly satisfied with my job, which is a privilege not many Spaniards enjoy. But I don’t think that Spain has recovered or will recover from the crisis in the immediate future.’

Like most young Spaniards, Maria blames ‘bad politics and politicians’. Rajoy’s Popular Party has been implicated in a string of corruption scandals over the last few years, and later in July the prime minister himself will appear in court as a witness in one such case — the first time in Spanish history this has happened. It is this ‘remarkably corrupt’ political class who are mainly responsible for the country’s lost youth, says Duncan Wheeler. ‘But it is also true that a blind eye was turned by many for as long as the country was getting richer. Low-level corruption and nepotism has also been endemic.’

A report released at the beginning of June by the Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS) said that 78 per cent of Spaniards aged between 17 and 33 think that their opinions are ignored by politicians. Over the past couple of years, this generation’s anger and disappointment have fuelled the success of two new parties in Spain, centrist Ciudadanos (‘Citizens’) and radical-left Podemos (‘We Can’), both of which have vowed to clean up the country’s politics.

Yet it is not just Spain’s younger generation and fresh-faced politicians who are disgusted with corruption, or see a glaring mismatch between stellar GDP performance and a broken labour market. In April, several leading Spanish economists sent a vitriolic letter to Jeroen Dijsselbloem, president of the eurozone’s group of finance ministers, accusing the EU and Spanish politicians of ‘scandalous manipulation’ of GDP figures and blaming them for generating ‘a gigantic bubble of debt … that will ruin the next generations of Spaniards for not less than 50 years’.

The strongly worded document concludes by observing that there is a growing chasm between the ‘actual economic situation of Spain’ and the situation as described by GDP growth statistics — a disparity that young Spaniards understand better than anyone. As Encar Novillo says: ‘The problem is that the foundations of Spain’s system are the same [as before the crisis]. Maybe the roof has been painted, but the house is still full of cracks.’

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

Comments