This election was won two days before it was announced, on Easter Sunday. Theresa May put out an Easter message in which she suggested that British values had a Christian basis. It was her version of David Cameron’s message two years before, in which he said that Britain is a Christian country. She was rather more convincing. I don’t know whether Cameron is sincerely religious, but he didn’t seem it. He didn’t even seem to try very hard to seem it, as if fearing that his metropolitan support might weaken, and perhaps that George Osborne would make a snarky jibe about it at cabinet. But it still did him good to make those pro-religious noises.

St Theresa should keep her piety out of politics, said a few pundits. Alastair Campbell adapted ‘We don’t do God’ into ‘she shouldn’t do God’: ‘I think even vicars’ daughters should be a little wary of allying their politics to their faith,’ he said, and accused the Prime Minister of suggesting that ‘if God had a vote he would have voted Leave’. A Guardian editorial warned that Mrs May’s message was part of a global move towards religious identity politics and ‘religious nationalism’. Do they say this every year about the Queen’s Christmas message?

Damian Thompson and Nick Spencer discuss whether politicians are allowed to ‘do God’:

Dangerous religious nationalism might be on the rise in other parts of the world, but that doesn’t discredit a British politician mildly affirming our main religious tradition. It’s Campbell and the Guardian who don’t get it. They don’t get that chippy secularism is a minority taste. Campbell ought to have noticed that Blair won three elections by doing a bit of God amid his politics, by making liberal Christian enthusiasm basic to his style. They don’t get that a huge sector of the electorate is vaguely reassured by soft Christian noises, and dislikes atheists implying that they are dodgy illiberals for feeling reassured. This blinkered approach to religion, seeing it as a veneer for nasty nativism, is hugely costly to its proponents: it is a major cause of the liberal left’s loss of mainstream appeal.

This election might pave the way for a realignment of progressive politics in Britain. But if a genuinely fresh force is to emerge, its ideological foundations must be right. And that largely means that it must formulate its approach to religion with great care. This is not a secondary matter that can be shrugged off, left to chance.

In my reading of the data, about a third of Britons are pro-religion, about 15 per cent are anti-religion and about half are pretty indifferent. A political party needs to appeal to that third, partly because it is the most civically engaged section.

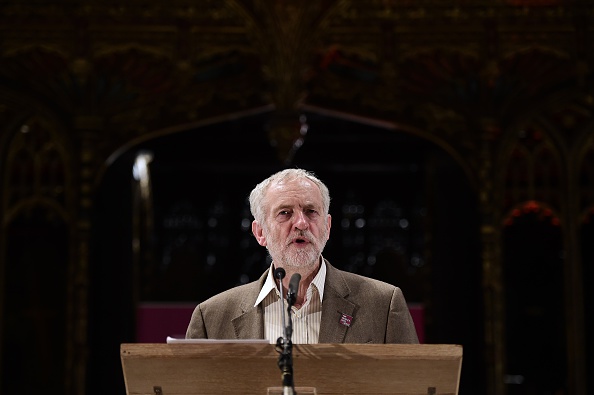

Hitherto, progressive politics has only half-grasped this. It has not quite noticed that pro-religion leaders are capable of doing a lot better than their sceptical peers, even in secular Europe. I would even say that a leader who identifies as atheist is a liability. In fact, so is a leader who is careful not to identify as atheist but basically is one. Which describes Jeremy Corbyn. He sometimes tries to sound religiously mysterious, but resembles an elephant hiding under a coat. In one interview he objected to being labelled an atheist, and said his actual position was ‘a private thing’. He went on: ‘I respect all faiths, I probably spend more time going to religious services than most people, of all types. I go to synagogues, I go to mosques, I go to temples, I go to churches, and I have many humanistic friends and I have many atheist friends. I respect them all.’

Can you hear the peeved tone? ‘Don’t I sit through enough faith events for people to leave me alone about my atheism?’ Corbyn’s (probable) atheism can’t really be separated from the rest of his winning personality. But it’s safe to say that it contributes to his lack of mainstream appeal, his failure to engage the Home Counties voter with a conscience who was wowed by Blair. The same was true of Ed Miliband. He once or twice tried to soften his atheism by pointing to its Jewish character. It didn’t work.

This should put Tim Farron in a strong position. But he has allowed himself to be boxed in as narrowly religious. A successful progressive politician (think Obama and early Blair) gives the impression of having a comprehensive, seamless world view, as if his politics and his religion effortlessly confirm each other, in a virtuous circle.

Behind the scenes it might not be so straightforward, but that’s another matter. Farron has proved that a liberal politician can’t afford to be seen as doctrinally conservative — he or she must exude sunny optimism that liberals and believers are fundamentally at one.

Whichever party emerges as the principal opposition this summer, it should seriously consider formulating an official line on religion. Otherwise its approach is too much defined by that of its leader, whose views on the matter might be muddled or superficial.

Incidentally, the Tory party doesn’t have the same need, for there is a strong assumption that its leader approves of the status quo, of the nation’s traditional official Christianity. Even an agnostic Tory can mumble something about being a flying buttress, supporting the Church from the outside. With a progressive party leader, one naturally wonders whether his or her reformism extends to wanting to reform religion away. So it would greatly help if he or she had a party line to refer to.

This party line should be: we affirm the role of faith in public life, and we see Britain’s shared moral values as largely deriving from its Christian tradition. This might seem an unnecessary foray into the history of ideas, but it is crucial for a progressive party to make this point about the roots of our shared values. Otherwise, its affirmation of ‘faith’ sounds like an empty bit of political correctness, dated multiculturalism. Otherwise, it is likely to perpetuate the old metropolitan progressive idea that religion is an oppressive neurosis: Marx and Freud left sufficient traces of themselves in north London to ensure the survival of this prejudice.

Progressive politics must make a decisive break with that Hampstead orthodoxy if it is to win over the crucial third of the electorate that is pro-religious. That means a new will to speak about the roots of political idealism — even if it embarrasses our English habits of evasion.

Of course I don’t mean that a progressive party must be overtly Christian. The secular nature of our politics must not be directly disrupted. Rather, a progressive party must make it clear that the humanist ideals it affirms are not at odds with religion, but are informed by Britain’s main religious tradition. It must say that progressive idealism has Christian roots — yes, it has other roots too, but the Christian roots must be foregrounded, so that the old Hampstead assumptions are rejected.

A politician who sneers at this idea, or fears that it heralds ‘religious nationalism’ is unlikely to appeal beyond certain pockets of north London, or to deprive Mrs May of any sleep.

This article originally appeared in this week’s Spectator magazine, out now

Comments