I was on the Question Time panel last night, and suspected that the issue of National Insurance might crop up – and that Karen Bradley, the Culture Secretary, would be sent out to defend the indefensible. Like all ministers, she has to repeat Philip Hammond’s bizarre claim that the Tories had not broken a manifesto pledge. That when they repeatedly promised not to raise National Insurance they meant only part of the National Insurance. The 2015 Tory manifesto contained no such caveat (I brought a copy along to the studio) and it’s impossible for any minister to claim otherwise. Hammond has already been accused of ‘lying’ – a strong word, but he should not be surprised if a politician makes a demonstrably untrue claim.

I wonder how many other Tory ministers will be sent into studios over the weekend, ordered to deploy this fictitious line of argument. Marr, Murnaghan, Neil, Peston, Pienaar – all will be waiting with sharpened knives for the minister foolish enough to tell their viewers that there was no manifesto pledge precluding a National Insurance rise.

The first question from the Question Time audience in Sunderland was a more subtle one: whether pledges can be reneged upon in the name of fairness. My answer was that yes, there might be circumstances that you can abandon a manifesto pledge. I’d like to see the triple-lock pension pledge removed, for example, because it’s too expensive and is intensifies cuts on the working-aged. But to do this, you need to level with the public. To admit that you’re breaking a pledge, and explain why. But to break a manifesto pledge and then pretend you haven’t by citing non-existent small print is so much more damaging to the Conservative Party because voters will conclude that Tories lie.

Such a reputation can be hard to shake off. During the 2005 general election campaign I was summoned to a briefing from Oliver Letwin, then shadow chancellor. He was announcing a bold new economic policy which I naively imagined might involve cutting the cost of government, or offering tax relief to low earners – something, anything, to offer an alternative to the debt-fuelled profligacy of New Labour. A chirpy Letwin then emerged to reveal his new promise: no more promises. No one would believe a Conservative promise on tax, he said, so they wouldn’t make any. He spoke as if this were a stroke of great genius – to me, it confirmed that the party was doomed.

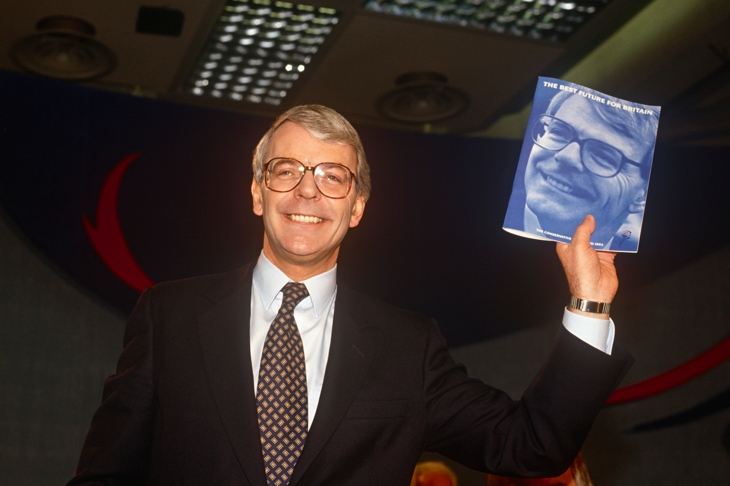

At the time, the Tories were still recovering from breaking tax promises made in 1992. ‘I have no plans to raise the level of national insurance,’ said John Major in January of that year. His manifesto went on to pledge to ‘to continue to reduce taxes as fast as we prudently can.’ In 1993, John Major’s government raised National Insurance from 9pc to 10pc. The Tory manifesto promise was a loose one, nowhere near as specific as the ‘no National Insurance rise’ of the 2015 manifesto. There was also an excuse, in the form of the Black Wednesday crash and devaluation of the pound. But the manifesto pledge was enough for Tony Blair to lampoon John Major’s government as a Cabinet of promise-breakers. An attack that worked with devastating potency. Perhaps more importantly, Blair argued – rightly – that the Tories had lost the right to pose as the low-tax party. And when Tories are robbed of the ability to persuade people they they’d cut tax, or at least freeze it, then one of their most powerful election weapons is disabled.

So it’s all just a little bit of history repeating: Tories making hard “read my lips” promises in their manifesto, then abandoning such taxes in power. For a paltry amount of money, Philip Hammond has now opened his party to exactly the same accusation that helped to fell the Major government. And left the Conservatives unable to make promises at election time for a generation.

Not until 2015 did the Tories feel confident enough to make manifesto promises on tax again. David Cameron did so haphazardly, never expecting to be leading a majority government that was expected to make good on these promises. So Theresa May may resent the manifesto, but it was the contract that she – and every Tory – made with the constituents who elected them. If she wants to tear it up, she’ll need a new election and a personal mandate. But she can’t break a manifesto pledge and either pretend that she hasn’t, or hope no one will notice that she has.

At The Spectator’s post-Budget briefing (a 300-seat sell-out) our sponsor, Old Mutual, made an interesting point about trust: it takes years to build, seconds to destroy and once knocked down it’s very difficult to repair. So it is with the credibility of manifesto pledges. Hard promises are powerful tools in an election – but only powerful if they are credible. As Nick Clegg said in his now-famous apology over tuition fees ‘we shouldn’t have made a promise we were not absolutely sure we could keep’.

The next time Philip Hammond looks over at the Liberal Democrat benches, he might ask: why are there so few of them? This is what happens nowadays to parties who go back on their manifesto pledges and allow themselves to be portrayed as untrustworthy. Betrayal of promises feeds into a general anti-politics mood, and the penalty for deception can be harsh. Yes, the tax rise is popular, especially amongst the 85pc of the workforce who are staff employees. The majority usually approve of taxes raised on the minority.

But Hammond should take no comfort in this. The question is not whether the tax rise on the self-employed is popular but whether anyone should trust a Tory manifesto promise on tax again. It’s a question that I, for one, would find hard to answer.

Comments