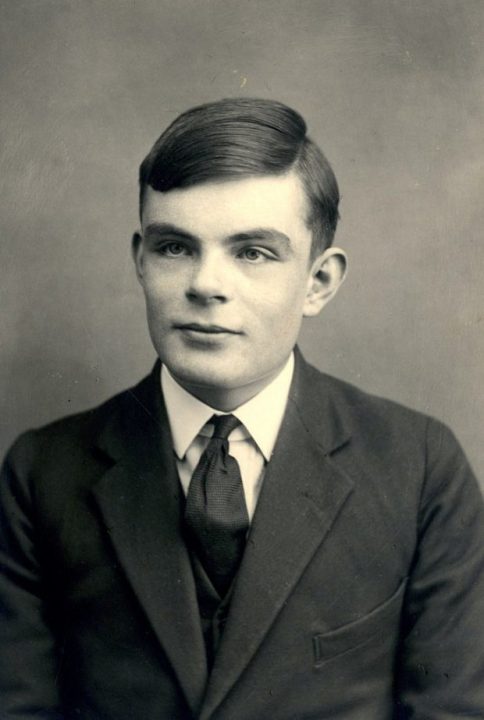

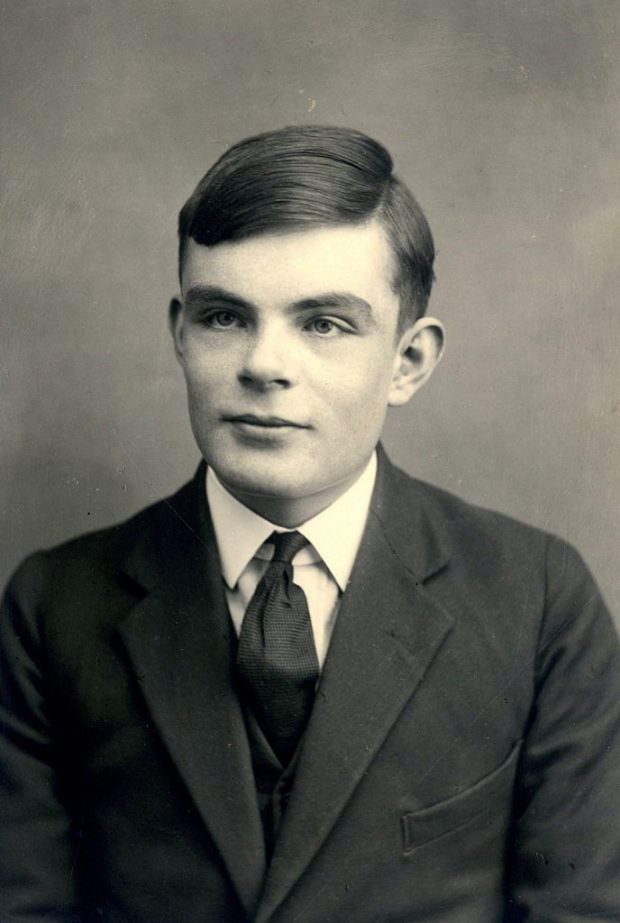

My invitation to the Pink News dinner (where David Cameron won an award) on Wednesday night promised ‘an inspirational evening’ which would be a ‘celebration of the contritions of politicians, businesses, and community groups’ after ‘another historic year for LGBT equality’. I assumed, at first, that ‘contritions’ was a misprint for ‘contributions’, but maybe not. Contrition for any deed committed or word spoken against gay people in the past is now compulsory for all who wish to take part in public life, rather as Catholics must be absolved before taking communion. I agree that the criminalisation of consenting, adult, private, homosexual acts was cruel madness. But I am suspicious of all this breast-beating. It privileges concern about one past injustice over many others, and it is displacement activity. We would do better to address current injustice than grovel for things we did not personally do. In every age, the relation between sexual acts and the criminal law is fraught, because of rows about mores, consent, policing and evidence. The biggest recent injustice in this area is the effective shift of the burden of proof from innocent to guilty against all those accused of child abuse. Instead of saying how sorry we are, 60 years later, about Alan Turing, we need to right whatever is wrong now.

Which reminds me that the new guidebook to Chichester Cathedral says the following about George Bell, the Bishop of Chichester famous for helping German Christians who resisted Hitler and for condemning Allied carpet bombing of German cities: ‘Since October 2015, however, some aspects of the way he is remembered have been called into question. An investigation into a claim of child abuse concluded that the allegations, whilst not tested in a court of law, are nonetheless plausible. His considerable achievements and their legacy remain, but it now seems entirely possible that the same man who showed moral courage in opposing saturation bombing was also responsible for the devastating abuse of a child. As Bell himself recognised, few people are either wholly good, or wholly evil, and supporting victims is always the right thing to do.’ It is rather creepy for the cathedral authorities to invoke the long-dead Bell’s own views to condemn his supposed actions. No doubt he did believe in supporting victims. The question is whether the one person who accused him of abusing her (nearly 70 years ago) actually was his victim. The process followed by the church authorities to establish this was perfunctory and unbalanced, and therefore unjust. I don’t think the guidebook’s phrase ‘entirely possible’ will do. Did he abuse her, or didn’t he? If it cannot be shown that he did, it must be assumed, in Christian charity and in law, that he didn’t. On its own logic, the guidebook should include a qualifying clause about Jesus of Nazareth. He, after all, was convicted by a court after serious allegations, which cannot be said of Bell.

This article is an extract from Charles Moore’s Notes, which first appeared in this week’s Spectator magazine

Comments