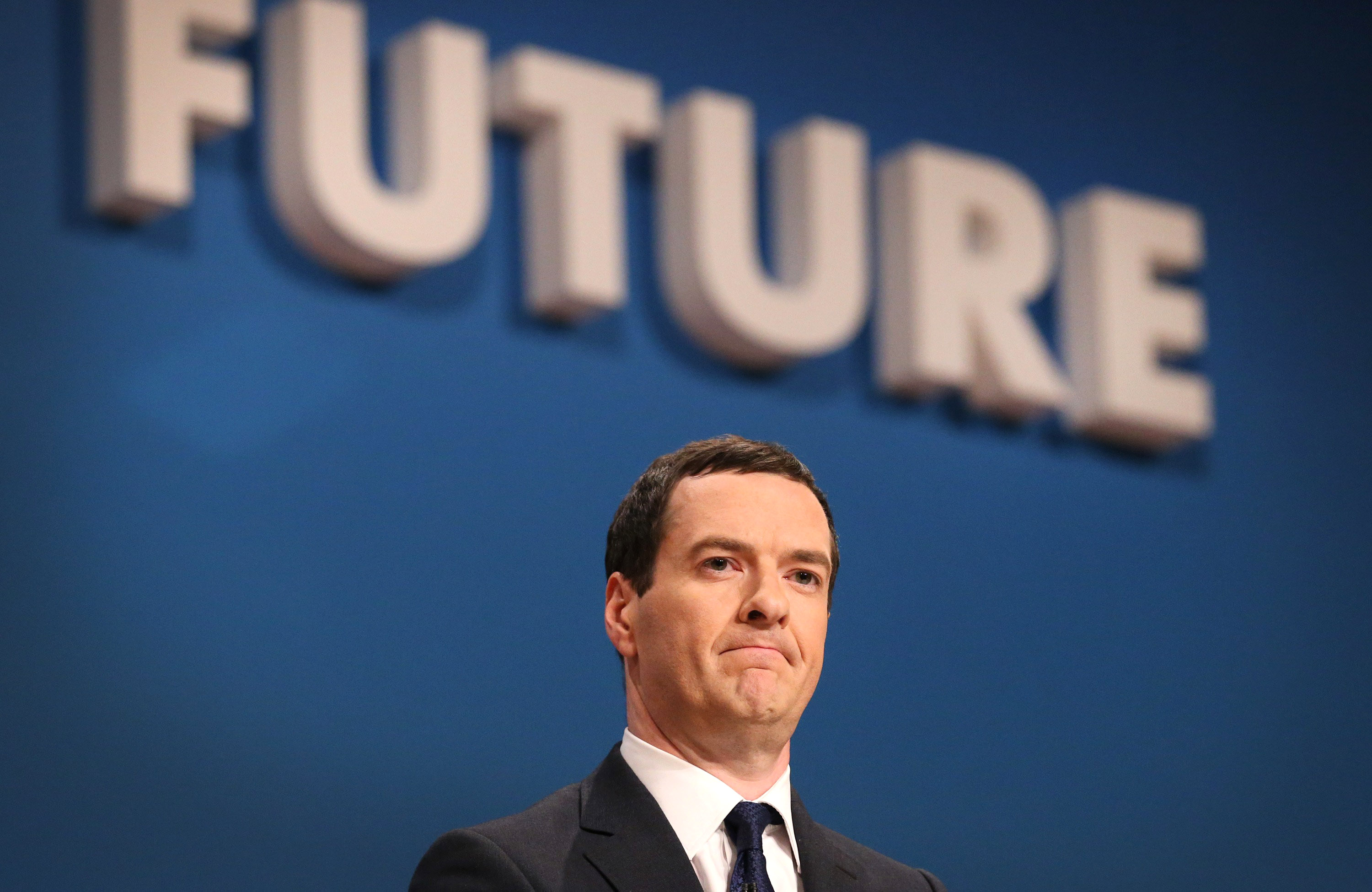

Without George Osborne, we’d probably be living under Prime Minister Ed Miliband right now. His value to the government goes far beyond his brief as Chancellor; he is across most departments most of the time. But as Chancellor, he is judged by the success (or otherwise) of his Budgets – which is why he is now in a moment of great danger. His love of complexity has come to threaten not just his own reputation, but that of the Conservative Party too. Sometimes, Osborne is so clever that he can be downright stupid: This is one of these times.

In my Telegraph column today, I say that Osborne is currently planning to soften – but not abandon – his tax credit cuts programme. So (for example) he’d set up a £1bn pot to help the worst-affected, but still tear £3.5bn from other claimants. This is an error. Tories should never be in the business of taking money away from low-paid workers who are doing everything the government asks of them. Osborne should phase in a leaner tax credits regime for new entrants (saving about £1bn), but not take money away from any families which already get tax credits. To do so would decrease the Chancellor’s savings by £3.5bn, a figure he can easily find by deciding to run a smaller surplus in 2019/20 (he currently plans a £10bn surplus). This plan is perhaps not clever enough for Osborne, but it the obvious one to follow.

Except the frustrated Treasury officials working on tax credits for him have been told not to look at this plan. The instructions he has given them are to find out how to save £12bn from welfare and in-work support, not whether. The £12bn figure was made up in the first place, and made worse when the Tories ruled out other things in a panic: no cuts for pensioners, or to child benefit, or to the winter fuel allowance etc. By the time the election was over, the only people unprotected were the working-aged. The pain would be focused on them. Again.

What could be worse than picking a battle against the working poor via tax credits cuts? Depressingly, Osborne has found an answer: open a second front in the battle against the working poor with cuts to Universal Credit as well. Yet this, I understand, is what Osborne is now planning: to finance a partial retreat in tax credit cuts by pushing the taper – in effect, a strivers’ tax – up to 75 per cent.

Let me introduce the strivers’ tax: Nowadays, low-paid workers claim various kinds of support: tax credits, income support, housing benefit etc. As you’d expect, the support comes down as wages go up. So you work a shift, it would make sense for workers to—ideally—keep about 60p in every £1 earned. But the system isn’t geared up like that. They can keep as little as 7p, because they lose 93p of benefits. This is called a ‘taper’ rate: in effect, a strivers tax. Ask yourself: would you work at a 93 per cent tax rate?

It is to David Cameron’s great credit that he made this the Tory cause. ‘What kind of incentive is that?’ he asked in 2009. In a wonderful passage, perhaps his best ever in a conference speech, he said that the Tories once obsessed about high tax rates for the rich. But his modern Conservative Party would now remedy high rates for the poor. Here’s the clip from his speech:-

‘Thirty years ago this party won an election fighting against 98 per cent tax rates on the richest. Today I want us to show even more anger about 96 per cent tax rates on the poorest.’

https://soundcloud.com/spectator1828/cameron-show-anger-about-96-tax-rates-on-the-poorest

He promises the Tories would ‘show even more anger’ about the strivers’ tax. But his Chancellor doesn’t seem to be so angry. Universal Credit was set up to put this tax at 55 per cent – still outrageously high, if you ask me, but the whole idea was to give policymakers the ability to change this strivers’ tax.

But instead, these powers are being to increase rather than cut the strivers’ tax. From the offset, the Treasury wanted it to be 65 per cent, a very high strivers’ tax. And now, Osborne plans to push it up closer to 75 per cent. As the Prime Minister once said, what kind of incentive is that?

Coming after the strivers saves £3.5bn. Osborne plans to increase the foreign aid budget by £3.5bn over the course of this parliament. So let’s not pretend that this is needed to cut the deficit – it’s about the size of the surplus. And let’s not pretend that there is no other way: the foreign aid budget could be ‘protected’ – ie, frozen – at its current record high levels. But in another example of being stupidly clever, Osborne wants the aid budget be the only budget in the British government that rises in line with economic growth. He is defensive about this target. As he puts it:-

‘I don’t believe in balancing the budget on the backs of the poorest.’

That was coalition-era Osborne. Are we to believe that the new off-the-leash Osborne, Chancellor with a Tory majority, now feels free to balance his budget on the backs of the poorest – as long as they’re British poor? Again, Osborne needs to ask himself: what kind of message does that send about him and his priorities? That the fashionable cause of overseas aid is protected at all costs, while a single mother working shifts can see her income fall by 10 per cent in the name of deficit reduction?

I do wonder whether anyone in the Treasury is pointing this out to him. Even if his only aim is to succeed David Cameron, does he really expect to do so after spending years increasing the tax on the strivers? And all for a sum that amounts to less than 0.5 per cent of government spending?

The irony is that Osborne has done so much for the working poor: his tax cut on employers helped create two million new jobs and his income tax cuts over the last five years have been helped the low-paid. His deficit reduction plan had to be abandoned because the jobs miracle was quite costly, due to in-work support. But it’s worthwhile trade-off. I argued at the time that Osborne should have boasted about this: he accepted postponed deficit reduction because he was forking out so much cash helping the unemployed back to work. Debt is cheap, and getting people back to work is a good investment when you consider the social harm caused by long-term unemployment.

[datawrapper chart=”http://static.spectator.co.uk/YpWgG/index.html”]

This could have been his personal legacy – but then he decided to make himself the scourge of the strivers. An epic act of self-harm – and unbelievably bad personal politics, let alone its effect retoxifying the Conservative Party that he hopes to lead.

Osborne has a short amount of time to go until the Autumn Statement where he’ll set out his solution to this debacle. He can save the working poor, the Conservative Party and himself by abandoning this madness and settling for a slightly lower surplus in 2020. A simple plan. But as I hope someone in the Treasury will tell him, some times, the simple plans are the best.

Comments