It is important, today especially, to remember that this is nothing new. We have been here before. On the 11th of July, 1991, Hitoshi Igarachi was murdered in his office at the University of Tsukuba. His crime? He had translated The Satanic Verses into Japanese. That was all. Eight days previously Ettore Capriola, the novel’s Italian translator, had been fortunate to survive an attempted assassination in Milan. And in October 1993 William Nygaard, the Norweigan publisher of Salman Rushdie’s novel, was shot three times. Mercifully and remarkably, he survived.

In fact, it had begun before that. On Valentine’s Day 1989 when the Iranian Ayatollah issued his fatwa against Rushdie. That was a test too many people failed back then. We have learned a lot since then but in many ways we have also learned nothing at all.

In 2012, Rushdie wondered if any publisher would have the courage to endorse The Satanic Verses if it were written then. To ask the question was to sense the depressing answer. They would not. Too risky, too provocative, too inflammatory. Too insensitive. Too dangerous. Sorry, mate, but we just can’t do it. Besides, you should have known what you were doing. Weren’t you, in some vague sense, asking for all this trouble?

No. No. Thrice No. Rushdie did not ask for trouble. Trouble was thrust upon him and everyone else associated with the publication of his novel.

It is worth dwelling on this today precisely because it reminds us that this morning’s Parisian horrors cannot be blamed on George W Bush or Tony Blair or neoconservatives or anyone else. The motivation for this barbarism long pre-dates their time in office.

Doubtless some will still, even now, find a way to blame the victims. Doubtless some will do anything they can to avoid looking reality squarely in the face. Doubtless some will pretend that reality can be wished away or that responsibility can be transferred to someone, anyone, other than the perpetrators.

Shame on those people. Shame.

Doubtless, too, there will be the usual calls on all Muslims everywhere to condemn these attacks as though they bear some inchoate communal responsibility for the barbarous actions of their co-religionists. This too will be drearily predictable and familiar and, most of all, desperately unfair. Their Islam has nothing to do with this even if it is also true that other subscribers to the faith do not share their views. The platitudinous suggestion Islam is a religion of peace is evidently, abundantly, true for the vast majority of Muslims while being utterly untrue for some. And so what? Where does that leave us? Only in a state of dread that’s matched only by its inadequacy.

To say these people are motivated by a perverted form of Islam is, in the end, pointless. Because it’s not perverted for them. Quite the contrary, in fact. They are the purest of the pure, the godliest of the godly. It is the real Islam as far as they are concerned. This will happen again.

Two conflicts rage here: one between civilisation and barbarism, the other between modernity and a kind of fanaticism we’ve known in our own past. As it happens, tomorrow is the 318th anniversary of the execution of Thomas Aikenhead in Edinburgh, the last man – though really little more than a boy – to be executed for blasphemy in this country. The Church of Scotland urged his execution the better to confront “the abounding of impiety and profanity in this land”.

But understanding or otherwise appreciating the manner in which today’s Islamist terror is in some respects little different from the Covenanting horrors of our own history is, in its way, an invitation to pessimism. We might wish for modernity to conquer Islamist barbarism in like fashion to which it was uprooted in the west and yet such hopes seem destined to be disappointed, not least since Islamist terror is direct repudiation of modernity.

Which in turns leaves us with little room for hope, little reason to expect that this story will change. It is a war, of sorts, in which we trust that reason can somehow – eventually – conquer a rejection of reason. This seems a forlorn hope today.

But what else can we do? Only, perhaps, this. We can hold the line. We can make our stand, a stand for liberalism and reason and liberty and we can hope – however flickeringly – that this will, in time, be enough to prevail.

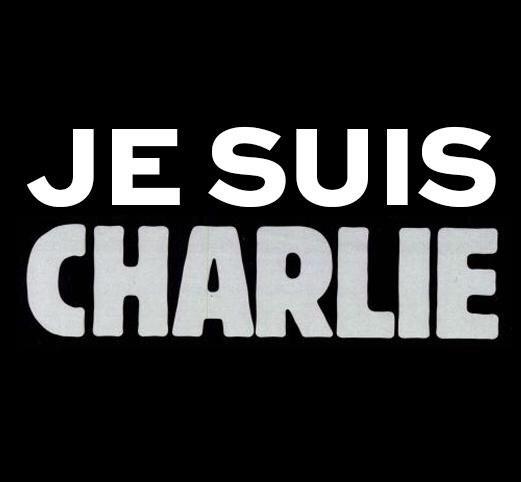

Je suis Charlie? In truth, I don’t know about that. I hope so. But, really, I don’t know if enough of us are Charlie Hebdo just as I know too few of us were prepared, 25 years ago, to say I am Salman. But there is no longer either the time or room to hide. If you were not Charlie Hebdo yesterday it is time, today, that you were.

That’s our faith. Here we stand. For otherwise what – and who – are we?

Comments