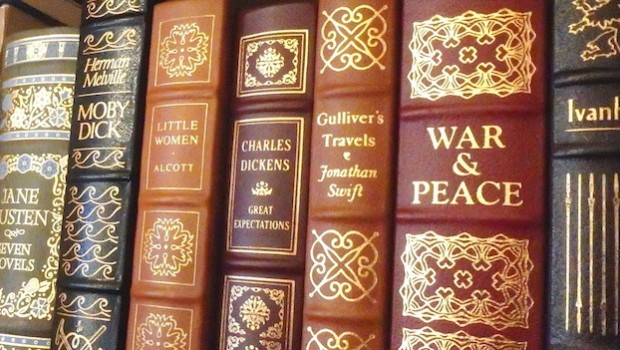

We all have what Andy Miller calls a ‘List of Betterment’: 50 or so books that, if read, would surely make us a better person – book clubs, gulp that Pino down, and discuss. Granted, it’s tough being a bastard if your nose is always in a book. And from The Year of Reading Dangerously: How Fifty Great Books Saved My Life, a memoir of 12 months spent working through a List of Betterment, it’s difficult to picture Andy Miller ever being a bastard. He’s a thoroughly amiable sort.

The reasons he decided to take drastic action with said list are simple. He explains: ‘We have been working parents for three years. In that time I have read precisely one book.’ He then sets off with The Master And Margarita, reads on through Middlemarch, stops off at The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, tears through Catch-22 and detours via A Hundred Years of Solitude. As with any journey, he ends up in a very different place to the beginning. In a year, he rediscovers what he knew so well as a lonely boy – aren’t all writers lonely children? – that reading is fun, and writing even more so.

There have been plenty of books on books that shaped lives: John Carey’s The Unexpected Professor, Rebecca Mead’s Middlemarch and Me or Hitler’s Private Library by Tim West. This is a fact-and-factoid-heavy, joke-saturated, appendix-tailed, light-hearted meander that owes more, judging from its tone and its nostalgic take on how culture shapes us, to Nick Hornby.

This List of Betterment does come with a health warning, however. Miller warns us the journey – the act of reading – and its final destination – that you might decide to produce your own masterpiece – are risky. But I didn’t get the impression that Miller was reading ‘dangerously’. There’s never an opinion (mainly about Twitter, libraries or Amazon) which surprises – which doesn’t obviously come from a nice, white, middle-class, literary type who eats Bonne Maman jam and reads the Guardian.

He’s in raptures over Anna Karenina and doesn’t like Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Of course, this is simply subjective, just a wonderful example of plurality of thought, and is immediately balanced by the fact that his wife likes it and his friends like it but he just couldn’t get along with it. While reading I found myself turning into Rod Liddle. Is that ‘Betterment’?

If you’re interested in the opinions of the bien pensants this may be the book for you. Some of his observations are perceptively familiar but, had you read any of the titles on his list, I doubt you would get anything new from his take. He amusingly explains why he hadn’t read any Patrick Hamilton before but still counted himself an admirer: ‘It seemed inevitable that I would become a Patrick Hamilton fan once I’d found the time to read him, so why refrain from assuming that identity in advance?’ On reading Twenty Thousand Streets Under The Sky, he praises Hamilton: ‘His politics inform the books but do not dictate them’. I haven’t read the book (appropriately) but I’m pretty sure I could garner that by only reading the introduction.

He’s right: one of the reasons no one bothers to get on with his or her List of Betterment, is that it’s quite easy to talk about something you’ve never read. The reverse is also true, which becomes a stumbling block for Miller: it’s hard to talk about something that you actually have read.

All of this bookish chat is interspersed with personal anecdotes and Miller’s opinions about various things. This ensures we’re never in doubt as to his amiable averageness but always in doubt as to why we’re reading this. He’s no Carey – or Hitler. The book stays true to its origins: a blog complete with pictures and the obligatory faux-confiding tone. But the confidences are minimal and played mostly for laughs. One of his friends describes him as ‘angry’. And certainly, I’d be angry if I’d read all these wonderful books, harboured desires to write and then ended up writing one on learning to love sport – with an extended chapter on crazy golf. I’d be furious. But Andy Miller never reflects on the gulf between his writing and this subject matter and the sad fact that writers, whatever they write, are usually left frustrated by their efforts. Given that he was an editor in a publishing house for many years, Miller should know it better than most. His previous career has undoubtedly helped in getting his blog into hardback.

Miller also reads Dan Brown and compares it to – oh the larks! – Moby Dick. He can’t help but admire the way in which the narrative drive propels you forward however sloppy the writing. This book is undoubtedly better written, and in most parts it’s warm and in a few places wise, but just like Dan Brown, after the final page is turned, and the final appendix skimmed, you can’t help feeling a little guilty, keen to read something more substantial and eager to get on with your own List of Betterment.

Comments