The status of aborigines in Australia has, to be frank, hardly crossed my radar until now. But that was before I met Tanya Hosch, a representative of the community who’s over here right now campaigning for them to get an honourable mention in the Australian constitution. ‘We just want to be acknowledged in the country’s foundational document,’ she says. ‘It really would make a difference to the way we feel that others see us.’

Australians, it seems, regard their constitution as a bit of a workhorse, clarifying various aspects of life without any of the grander aspirations of the US constitution. Most of them aren’t really aware that aborigines are absent from the constitution in the first place. Tanya is too polite to say baldly that they were there first but given this obvious reality, it seems odd, to say the least, that there’s no mention of them. In New Zealand, by contrast, there is a treaty between Maoris and the rest which allows for the subject to be endlessly debated. Six years ago the state made an apology to the Aborigines for the raw deal they got since Captain Cook, but it’s not quite the same as a constitutional mention.

Thing is, any change to the constitution requires a referendum. And in Australia that means a majority not just of voters but of states: so four of the six states plus at least 51 per cent of votes. Hence Tonya’s presence in London, lobbying the Australians here. But the normal objection to referendums, viz, that people can’t be bothered to turn up doesn’t apply there, on account of their – to my mind admirable – compulsory voting system. The effect of it is to shift politics to the centre ground, for since everyone’s voting – apart from those with $120 to burn (that’s the fine for not turning up) – you have to appeal to the mainstream. So, the constitutional amendment will be a moderate affair; the wording is still being worked out. Naturally, there’s disagreement on what it should involve, even among aborigines (some of whom feel it doesn’t go far enough) but it’s likely to be a formula designed not to alienate anyone.

Now, it’s a fair bet that if this sort of campaign were happening in Britain, it would be squarely dominated by the Left and an assortment of campaigners for inclusivity, diversity, anti-colonialism, multi-culturalism – you know, the usual . Thing is, it hasn’t happened in Australia. Tanya points out that constitutional change has, historically, remarkably, been the preserve of conservatives. There have been only 44 attempts to amend the constitution and of the eight that succeeded, seven were sponsored by conservatives.

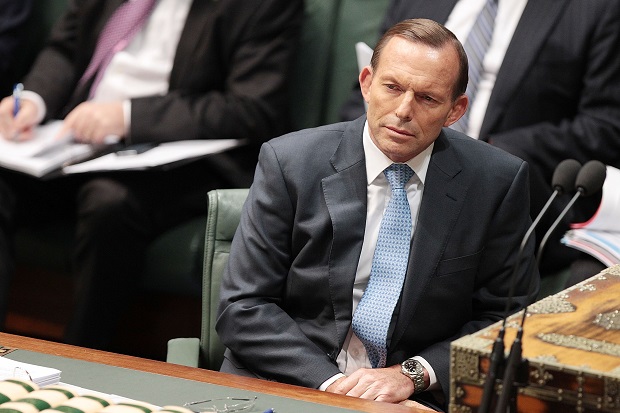

Well, it’s true of this campaign too. One of its leading supporters is Tony Abbott, the Australian Liberal premier. Indeed, he gave a moving and powerful speech on the second reading of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Bill last year in the House of Representatives in which he called the failure to recognise the first people as ‘a stain on our soul’. He went on to observe, ‘Our challenge is to do now in these times what should have been done 200 or 100 years ago: to acknowledge Aboriginal people in our country’s foundation document. In short, we need to atone for the omissions and for the hardness of heart of our forebears.’

In passing, let me observe that this is as near to the Catholic Confiteor, or confession of sin, in a political speech, as I’ve ever come across, and Mr Abbott is a Catholic. But the interesting thing about all this is, from the point of view of Speccie readers, that constitutional reform and the acknowledgement of aboriginal rights is, here, not just a leftie thing but a conservative thing. Indeed, if socially progressive reform is going to get anywhere, there’s a better chance with the right – in this case the Liberal Party. Tony Abbott is loathed and vilified by his political opponents to an extent that hasn’t been seen here since Margaret Thatcher. Interesting, isn’t it, that he should be on the vanguard of social progress?

Comments