It’s been 25 years since the Iran-Contra affair – the scandal about the US

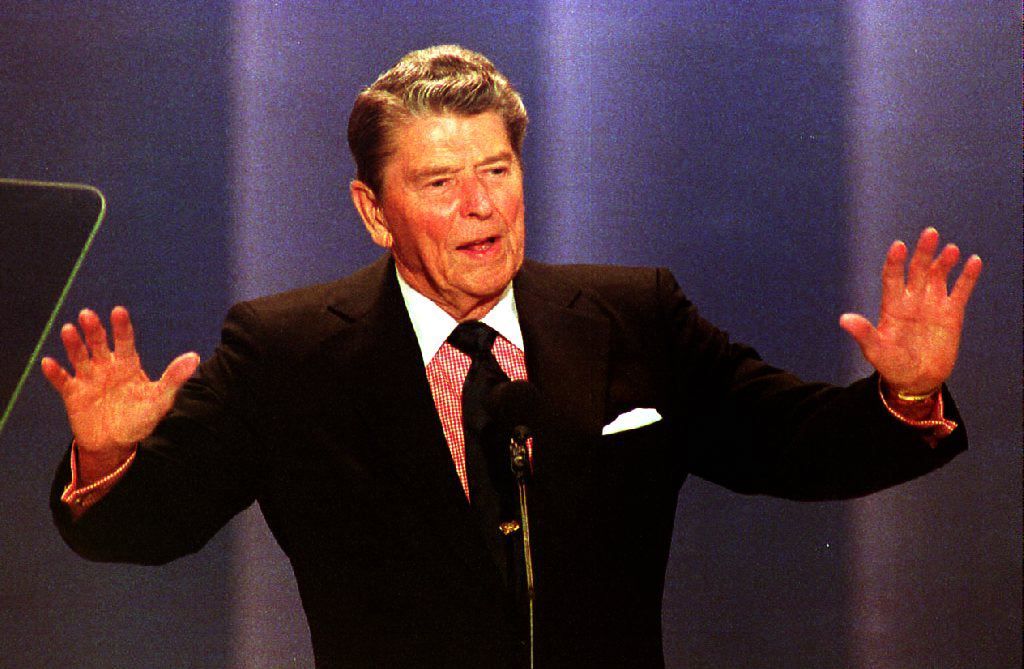

government selling arms to Iran and using the proceeds to fund the Nicaraguan rebels. It saw Ronald Reagan’s approval rating drop from 67 per cent to 46 per cent, and fourteen memebers of his staff

were indicted. In a piece that appeared in The Spectator exactly a quarter of a century ago, Christopher Hitchens explains how the Reagan administration was unable to contain the

story.

It’s been 25 years since the Iran-Contra affair – the scandal about the US

government selling arms to Iran and using the proceeds to fund the Nicaraguan rebels. It saw Ronald Reagan’s approval rating drop from 67 per cent to 46 per cent, and fourteen memebers of his staff

were indicted. In a piece that appeared in The Spectator exactly a quarter of a century ago, Christopher Hitchens explains how the Reagan administration was unable to contain the

story.

The end of the line, Christopher Hitchens, 29 November 1986

If you wish to understand the fire that has broken out in the Washington zoo, and penetrate beyond the mere lowing and baying of the trapped and wounded beasts, you must master three key concepts in the capital’s vernacular. These three – all of them coined by the White House itself – are ‘damage control’, ‘the line of the day’ and ‘reality time’. Damage control is the art, perfected until recently by Donald Regan, of giving way without yielding an inch; of taking an inconvenient leak or revelation and placing it in quarantine. One may trump it, for example, with another leak less damaging but more newsworthy. One may change the subject by holding a press conference at which the President announces a bold new ‘initiative’. And of course one leans heavily on the indubitable fact that the press and public opinion have distinctly short memories.

Essential to damage control is ‘the line of the day’, a routine that was instituted at about the time that Regan became White House chief of staff. Blindingly simple, like all great ideas, it calmly stipulates that all members of the executive branch spend a few minutes each day co-ordinating their story. It is then fit for endless iteration, and the resulting front of unanimity will depress any bothersome scribbler or congressional invigilator. It need last, at a pinch, no longer than it takes to get to ‘reality time’.

‘Reality time’ is the White House term for the seven o’clock news. According to David Stockman in his intentional memoir of the Reagan style, this is when Meese, Reagan, Regan, Buchanan e tutti quanti hold their breath. Once they are over the frail hurdle erected by Dan Rather, Peter Jennings and the other stars, and the word ‘split’ has not been employed, then the team can relax. They may not need a presidential press conference after all.

The most brilliant illustration of the process was at Reykjavik, when even the dullest eye could see the woe on George Shultz’s face and when there was keen speculation about failure and recrimination in high places. Damage control took over with a meeting that was actually held on Air Force One on the way home. A line of the day was established, which was that no ‘agreement’ had ever been sought in Iceland. Iceland was a test of resolve on Star Wars, not the beginning of arms control at all. Division, what division? This line, repeated loudly and assertively and ad nauseam, just about got past the scrutiny of reality time. It held up through the midterm elections, though there was one nasty moment in Chicago when Reagan spoke of ‘building on the agreement we made in Iceland’. Clarifications were issued, smokescreens were laid down, the subject was changed and Reagan got through the entire campaign without giving one live press conference.

You can see why the presidential press conference is considered a last resort. In the case of the Iranian arms fiasco, it came only after a flurry of denials, several artful changes in the line of the day (from humanitarian concern for hostages to the strategic importance of Iran and back again) and a full-blown autocue address by the President immediately after reality time on Thursday 13 November. It was only when the opinion polls revealed a public sales-resistance to the line of the day, and only after the line itself had been publicly broken by an outraged Shultz, that the gates of the White House were reluctantly opened to the questioners. And the harvest, on 19 November last, was the pitiful spectacle of a mad old tortoise at bay that has dominated the discussion ever since. Messrs Reagan, McFarlane, Shultz, Regan and Speakes cannot all be telling the truth. In my opinion they have all lied. But there is no line of the day, and reality time has turned all too real, and damage control is beyond repair.

Compare the Reykjavik lying with the Iran lying and you will see what makes the difference. Reagan said that the proposal in Iceland had been to ban all strategic missiles in five years, and that the arms sent to Iran were few, defensive and could be carried on shoulders. Actually, the vanquished proposal in Reykjavik was for a ban on ballistic missiles within ten years, and the anti-tank weapons sent to Iran could equip three divisions, are hardly ‘defensive’ given that Iran is pushing south, and are so heavy that they have to be mounted on jeeps. The first lie is complex and requires a sustained interest in the subject of arms control to reveal itself as an absurdity. The second is specific, checkable and, in a sense, much more conscious. It is also much more readily detectable by an average newspaper reader. So is the claim that the weapons had nothing to do with the release of the three hostages – a release for which Reagan then claims his arms sales policy is responsible! (I almost never employ exclamation marks, but that seemed to warrant one.)

Analogies to Watergate are too easily made, but may turn out to be more profound than they first appear. Of course Watergate involved the changing of the official story, the rendering ‘inoperative’ of previous versions and all the rest of it, to a point where nothing the President said was believed for a second. (It also involved, interestingly enough, a refusal by George Shultz to supply Nixon with the tax returns and private invoices of his political critics.) But the often-forgotten genesis of Watergate was the need to conceal certain aspects of Nixonian foreign policy. ‘The plumbers’ evolved as a squad for use against those who leaked the secret bombing of Cambodia and the other, even less decorative, initiatives of Dr Kissinger. That’s where the bugging began.

It is also where congressional indulgence stopped. The fiascos and humiliations in Chile, Indonesia, Cyprus and Bangladesh led the House and Senate to retrieve much of the influence they had lost over war-making and foreign intervention. You can read the entire ‘Reagan revolution’ as a concerted attempt to roll back the gains made by the Fulbright and Church committees in the Seventies. And, just as it was the later humbling of the United States in Teheran that shifted public opinion towards tougher, less circumscribed executive action, it is the Iranian imbroglio that has recalled a sleepwalking Congress to its responsibilities. From now on, it is very likely that the National Security Council – that bats’ nest of Poindexters, McFarlanes and Norths – will have to submit its mysterious membership to confirmation by the legislative branch. Reagan has not merely excluded Congress, he’s excluded the State Department. We may not automatically do better, say the Senators, but taking one consideration with another we could scarcely do worse.

The question which, reiterated, brought down Richard Nixon was, ‘What did this President know and when did he know it?’ On Tuesday Reagan claimed, astoundingly, that an operation involving Switzerland, Israel, the CIA, Iran and Nicaragua had been conducted without his ‘full’ knowledge. I don’t care for that ‘full’, and I think he will regret it. The secret war on Nicaragua has been ‘his’ war in just the same way as the shady dealing with the mullahs was ‘his’ deal. Dr Henry Kissinger – the other unindicted Watergate survivor – has a maxim of real quality for these occasions. It is that anything which is going to have to be confessed ultimately should be confessed now, and anyone who is going to have to go eventually should go at once. Poindexter and North have gone – but they were military men who took orders as well as giving them.

All this will be the stuff of policy-making and debate from now until the end of this presidency. But in looking ahead one mustn’t be blasé about the story of the week. The story of

the week is the final rumbling of Ronald Reagan. Readers of Dr Oliver Sacks’s wonderful casebook The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat may recall the opening paragraph of the essay

entitled The President’s Speech:

Sacks explains that the chief property of aphasia – the loss of word recognition – is accompanied by a compensation:What was going on? A roar of laughter from the aphasia ward, just as the President’s speech was coming on, and they had all been so eager to hear the President speaking… There he was, the old Charmer, the Actor, with his practised rhetoric, his histrionisms, his emotional appeal – and all the patients were convulsed with laughter. Were they failing to understand him? Or did they, perhaps, understand him too well?

There has been a great change, almost an inversion, in their understanding of speech. Something has gone, has been devastated, it is true – but something has come in its stead, has been immensely enhanced, so that – at least with emotionally-laden utterance – the meaning may be fully grasped even when every word is missed.

In fact, as clinical neurologists will tell you, it is impossible to lie to an aphasic because aphasics have ‘an infallible ear for every vocal nuance, the tone, the rhythm, the cadences, the

music, the subtlest modulations, inflections, intonations, which can give – or remove – verisimilitude to or from a man’s voice’. Sacks concludes, from the ridicule and

contempt with which his patients greeted a Reagan broadcast, that:

For the past several years I have been attempting to parse Reagan’s speeches; to convey a sense of their falsity as well as their success. In this week of vindication, I am willing to admit to aphasia in order to join the suddenly swollen ranks of ‘the normals’ who hasten to emphasise that they had, really, seen through him all along.We normals – aided, doubtless, by our wish to be fooled, were indeed well and truly fooled (‘Populus vult decipi, ergo decipiatur’). And so cunningly was deceptive word-use combined with deceptive tone that only the brain-damage remained intact, undeceived.

Comments