Theodore Dalrymple has an article in this week’s issue of magazine (non-subscribers can buy the Spectator from just £1 an issue), on the nihilism of the young. Roy Kerridge came to very similar conclusions during the Brixton riots of 1981.

Here’s what he made of them:

Theodore Dalrymple has an article in this week’s issue of magazine (non-subscribers can buy the Spectator from just £1 an issue), on the nihilism of the young. Roy Kerridge came to very similar conclusions during the Brixton riots of 1981.

Here’s what he made of them:

A day in Brixton, Roy Kerridge, The Spectator, 18 April 1981

Some years ago I noticed that all was not well with some of the teenage children of my West Indian friends. After reluctantly being pushed out of their schools – where they really did spend the happiest days of their lives, going on treats almost every week – they simply went home and behaved as if they were children on holiday. Their twentieth birthdays came and went, and there they were, raiding their mothers’ handbags and playing records at one another’s houses. They were not even ‘unemployed youth’, as they didn’t bother to sign up on the dole, avoided work and lived by cadging and occasional petty thefts. A whole new world of big, cheerful, coloured youth appeared, none showing any signs of growing up. Their parents blamed them for not passing exams, but people have lived honestly and well long before exams were invented and will do so, presumably, when exams are forgotten. Stabbings and violence began to occur among these young people, in arguments over girl and boy friends. Children who had sat on my knee ended up behind bars. An anti-police philosophy appeared, and routine questioning or being asked to move on came to be regarded as ‘police brutality’. Western Indians were growing old and retiring, and ‘the blacks’ were born, an overlap generation, very unsettled and neither English nor West Indian. The troubles in Brixton were mainly the work of ‘the blacks’.

Brixton Market on Monday morning was a busy sight. No stalls were out, but glassfitters’ van were everywhere, as the shop windows were replaced and boards nailed up – business almost as usual. I am told that such quick repairs, done amidst humorous banter, are a feature of Belfast. I noticed the anxiety of assistants in a left-wing bookshop selling tracts that urged ‘young blacks’ to attack the police. They decided to close early for safety’s sake.

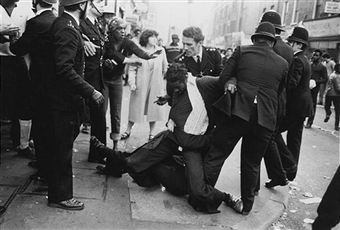

In Coldharbour Lane, young Rasta-like men stood on the pavements laughing and joking and looking with triumph at a burnt out building. I felt rather ashamed to be among the obvious sightseers, including some left-wing fringe press, who wore punk badges. Shopkeepers, keeping a lookout on the road, grumbled about ‘West End holidaymakers’. Broken glass littered the pavements, and everyone seemed to be waiting. The crowd of muscular young men outside a reggae record shop looked the most evil people I had ever seen in my life. A man with a film camera was warned off in no uncertain terms.

An elderly West Indian lady with a shock of white hair suddenly panicked and shouted ‘Trouble! Trouble!’ She ran down the road, but her friends stopped her, as nothing had happened. ‘I’m getting out of Brixton!’ she exclaimed. All the other West Indians seemed to expect trouble to come from the young people, not the police. The men, however, seemed not displeased, but almost proud, as if saying, ‘See what our young people can do’. As for the old lady, when she calmed down, she began to rail at those who blamed ‘black youth’, saying that ‘white young people are the worst’. This I can believe, for uproariously happy youngsters ran up and down the streets, white and coloured together, looking for mischief. Some of them told me horror stories about the police, saying that a one-year-old white baby had been beaten up.

These young people seemed no worse than most roller-skating cigarette-puffing boys in any part of Britain. They had a point when, in the pages of the Sun, they showed a small coloured boy, ‘our mate Colin’, being sat on by three enormous policemen. But most of their stories seemed fantastic. Down at Railton Road, some houses were burned to the ground; others showed bare roof beams to the sky. There I saw the cameraman again, being manhandled by a hostile crowd. ‘National Front!’ a middle-aged man woman shouted, obviously mistaken. A huge pub, The George, was completely destroyed. ‘Black militants’, or youth dressed for the part, swaggered about the streets, puffed up with pride, their hour come at last. Pleasant-looking West Indians, such as I am used to, were noticeably absent.

In Atlantic Road I stopped at the Community Arts Centre, where the mainly white crowd were in high spirits. They cheered as another cameraman finally had his film torn away; a wild-eyed Rasta bore it into the Community Centre, and waved it triumphantly aloft. ‘I’m on the blacks’ side,’ said a determined-looking young woman there who gave me some delicious homemade bread. ‘It’s all because there are no playgrounds for the children here, and nothing for the young people to do’. I looked up and down the devastated street and said nothing. One of the young boys I had spoken to, Pascal Brennan, of Irish descent but quite at home in Brixton, told me urgently to ‘be careful, talk kindly to people, as they’ve beaten up one journalist in Railton Road already.’ Police vans were arriving, and a new bout of fighting seemed to be imminent. I adjourned to the public library to write my account, but the head librarian regretfully announced that it was closing early ‘because of the troubles’. All the coloured youth studying there groaned, picked up their armful of books and trooped into the uncertain streets outside. Wild-looking young people of all colours, aged from 12 to 30, were heading jauntily towards Coldharbour Lane from all directions. What would the evening bring?

Comments