The crisis in Greece shows just how quickly a fiscal crisis can blow up. Just two-and-a-half weeks ago, Greece was able to raise several billions in financing, with demand for almost 25 billion of their debt in an auction. The very next day, their bond market collapsed and the rout began. Just ten days later, they were turning up in Brussels with a begging bowl, and inviting the European Commission and IMF to Athens to start making their tax and spending decisions.

There can be nothing worse for a government than having your economic policy dictated by the markets, and then other governments, as access to finance disapears. All you can do is rush out announcement after announcement, promising tax hikes and spending cuts, and pray that the market pressure eases up. While the usual weeping and wailing about evil speculators and short-sellers hits the headlines – a familiar ruse to those in the UK from the bank collapses – the reality is that the willingness of international markets to lend further has been exhausted. The endgame has begun.

Few should understand the dreadful nature of this experience better than David Cameron. Watching Norman Lamont and John Major rush in front of the cameras in 1992 – promising ever higher interest rates and economic pain to assuage markets – will have been a powerful lesson in just how overwhelming the markets can be when confidence is lost.

Something lost in the memory of the 1992 experience was that other countries were having similar pressures – Canada, Australia, Sweden, Finland and Italy in particular. The commonality was that all had high – and, to many investors, unsustainable – deficits. That year saw bond markets and currencies collapse like dominos. Country after country was forced into sorting out its debt position, as markets withdrew the national credit card. The memoirs of the leaders of the left wing Canadian and Swedish governments at time make clear just how terrified their governments were of being forced into the hands of the IMF. It was the firm view of the left in those countries that they had to get the national finances under control quickly, lest their ability to provide the social safety they wished became unsustainable.

Ultimately, the history of running deficits this big is pretty clear cut – at some point the bond market explodes and carries you out. It’s when, not if. A country with very high household debt and a shaky banking system is particularly vulnerable.

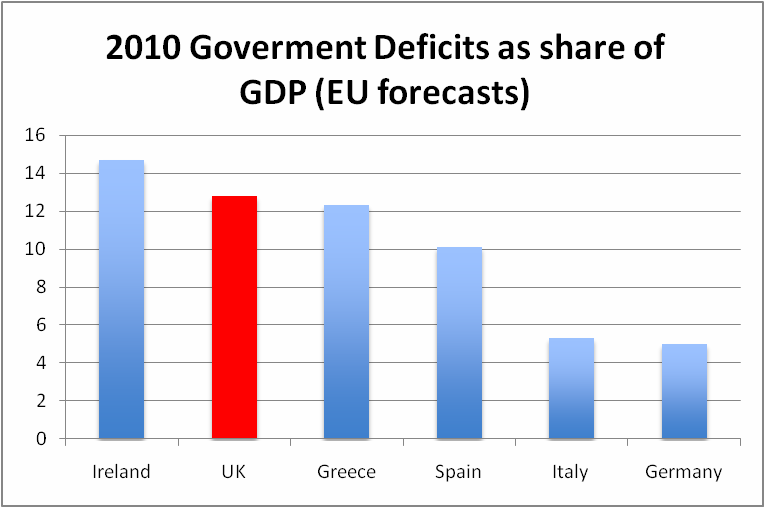

Which is why this chart is particularly ominous. It shows that the UK deficit is the same size as that of Greece:

Cameron and Osborne seem to have been thinking about this more than most, and recognise the constraints their government will be under. They seem to realise that they are going to have to face up to some very different decisions and need to warn people. And so it will start becoming clearer that the guy who says, rightly, that “we can’t go on like this” is a very different kind of politician from the guys who arrived singing “things can only get better.”

Comments