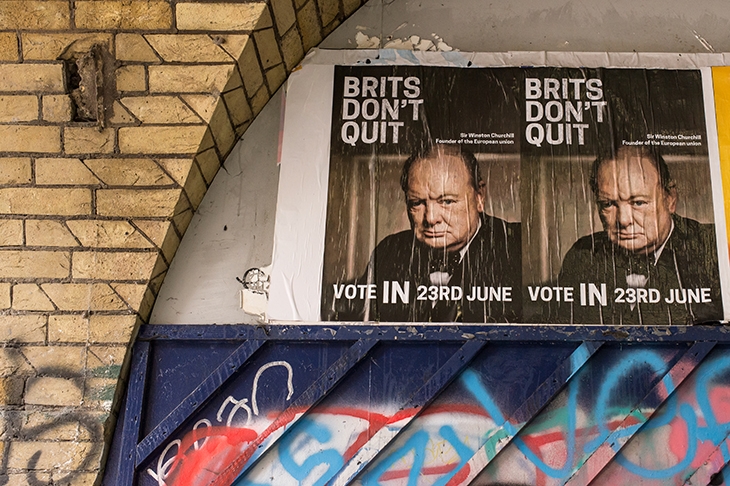

How we love bringing history into our political debates. It may seem strange in a country where so little history is taught at school, but perhaps that makes it easier. We grab hold of vague notions of the past for a Punch-and-Judy brawl. There could hardly be a better example of this than Brexit, in which we skim through the whole of our history to search for analogies to batter the other side with. The Roman empire, the Norman conquest, the Wars of the Roses, the British Empire, appeasement, the second world war, Suez…

Leavers have fulminated against ‘traitors’ who deserve the Tower for flouting Henry VIII’s assertion of sovereignty. Remainers have accused Leavers of being racists, imperialists, indeed, worse than Nazis. On a brighter note, Iain Duncan Smith’s recent comparison of Brexit to the Reformation talked of its ushering in a golden age when Britain ‘led the globe’. Professor Simon Schama, denouncing ‘dunces’ who use history to illustrate simplistic ideas, points out the Reformation was a European phenomenon that produced a long period of religious mayhem.

What much of this pseudo-historical polemic has in common (apart from a desire to annoy the other side) is that it tries to create a sense of inevitability and drama. Rather than Brexit being a proper subject of rational argument and democratic choice, it is presented, especially by hard-line Remainers, as being outside the proper ambit of the electorate. Because we are and always have been ‘European’, we must remain in the EU. One could hardly come up with a more simplistic idea than that.

As for the drama, it hardly needs illustration. A subject that until 2016 seemed a technical issue that bored most people rigid has been blown up into an existential struggle.

As a professional historian, I’m sorry that ideas about history have provided much of the material for the hysteria. Admittedly, they are usually rather inaccurate ideas. This is one of the ways in which the past influences the present: not what happened, but what we choose to believe. It would be sensible to drop historical analogies altogether, but this will certainly not happen. The next best thing is to try to untangle some of the beliefs on both sides.

On the Leave side, probably the most influential idea is British exceptionalism: we have ancient historical, legal and political traditions that make us resist undemocratic European federalism. There is some truth in this. In particular, our collective experience of the 20th century makes us less committed to the notion of ‘ever closer union’ as the antidote to a new dark age. I rather doubt that earlier centuries have much influence on our decision. Moreover, many other Europeans take a similar view of themselves: we are less exceptional than we think.

On the Remain side, there is more of a mishmash. One endlessly repeated assertion is that the EU guarantees European peace. There is little substance in this idea: the defeat of Nazi Germany, Nato and the spread of democracy are weightier causes. Meanwhile, belief that European unity is a triumphant historical inevitability seems to have faltered, replaced by a pessimistic assumption that the rise of China means that hanging together in an increasingly troubled EU is our only hope. If history has shaped this view, it is the echo of the 1960s’ fear that without an empire Britain was so weak it needed to cling to the Common Market. A similar view now exists in France. Both are historically dubious.

Over recent months, however, the Remainer argument seems to have become less about the EU itself and more about the iniquities of those who support leaving it, tarred as nostalgic imperialists and xenophobes. This seems to me both worrying and interesting as a historical phenomenon. It’s too early to be sure whether it reveals a pre-existing divide, or is a new antagonism, but my guess would be a mixture of the two.

There has long been a current within Britain suspicious of its own national identity. In 1941 George Orwell famously observed that British intellectuals would prefer to be caught stealing from a poor box than standing up for the national anthem. At that time this was linked with admiration for Stalin’s Russia. But there is a longer history of progressive utopianism that believed fervently and successively in free trade, the League of Nations, pacifism, appeasement, the United Nations, CND, third-world Communism, and now an idealised EU.

The feeling of not being fully part of a nation symbolised by monarchy, a triumphalist history and, at one time, established churches, has deep roots in ‘the nonconformist conscience’ and 19th-century anti-imperialism. It remains particularly visible among the ‘left-behind’ middle class of educated and undervalued public-sector workers, who see Brexit as the triumph of the Tory elite. The EU has become merely the latest backdrop to an ancient quarrel.

Is this a uniquely British divide, heralding a break-up of the United Kingdom long anticipated by nationalists and some on the left? Yes and no. Like Tolstoy’s families, unhappy countries are all unhappy in their own way. But an alienated minority — indeed, often several — is a fact of life in most countries, not just ours. The United States is more divided than we are. If Germany or France voted to leave the EU they would have equally bitter and almost certainly more violent conflict — the reason why their politicians will do everything to avoid it. And think of Spain, Italy, Greece …

Time will tell how deep and long-lasting Remainer alienation will prove if and when we reassert national sovereignty. Until galvanised by the shilly-shallying of the May government, the ideologically motivated pro-EU minority was tiny. It has grown apoplectically vocal, but is it much bigger? Most people who voted Remain did so from economic worry. But the doom-laden predictions of economic catastrophe have deflated and should continue to deflate. Given the EU’s chronic problems, and the majority of the country that remains attached to the principle of national democracy, it is hard to imagine a future Rejoin movement flogging the dead horse back to life. But the first lesson of history is unpredictability.

Comments