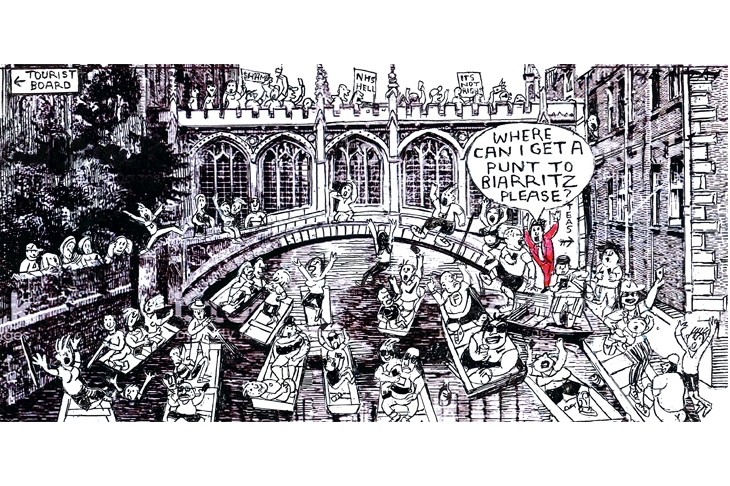

Sharing a plate of oysters with a three-year-old: where could this be but France, where children are brought up not to be faddish. The fads are for adults. It’s a relief to be away from Cambridge, where summer is bad for the soul. I find myself getting constantly annoyed: with suicidal cyclists, psychopathic taxi drivers, imbecilic pedestrians and double-decker buses allowed to hurtle through narrow streets belching diesel fumes. And hundreds of thousands of tourists trooping gormlessly up and down King’s Parade with not much to do. Here in Biarritz, the streets are calm, the traffic is regulated and people do not shout at each other in the street — a regular occurrence in Cambridge (and, mea culpa, one of the shouters is sometimes me). Biarritz is a town that lives by tourism and adapts to it. Cambridge has tourism dumped on it, and it fails to cope. Biarritz shows signs of having someone in charge. Whereas Cambridge is full of egos, has no sense of community, and its habitual summer state is one of nerve-jangling chaos. On the other hand, one doesn’t experience the sudden shock of seeing a squad of paratroopers in combat gear threading their way between the children with beach balls and the old ladies walking their chihuahuas.

In Biarritz I can indulge a vice: fromage de tête. Beside the covered market — itself a temple of gastronomy — is a traiteur whose profusion of beautiful and delicious treats outshines a dozen restaurants. Fromage de tête is one of the least glamorous, but has helped to win its maker the title ‘meilleur ouvrier de France’, which is conferred on outstanding craftsmen. This is still a country where you learn how to do things properly and with pride. It’s often said to be a dying tradition, but here, as the queue shows, it thrives.

Something I’m childishly proud of: I swim in the sea unaided for the first time, plunging headlong into the Atlantic surf. I never learned to swim until now, in my sixties, thanks to my brilliant teacher Helen at Parkside swimming pool. Coming to it late in life means you fully appreciate its sensuous thrills — at least, so I tell myself, to compensate for decades of lost fun.

Off to stay at a friend’s château (not a sentence I could often write) deep in the countryside, where we are temporarily cut off as the roads are closed for the Tour de France. En route my wife Isabelle and I catch the beginning of the Fêtes de Bayonne, a reminder that the Basques are a particular people: gregarious, uproarious, fond of a drink (euphemism) and sometimes of a punch-up afterwards. The city centre is crammed with people dressed in national red and white, the men with piratical scarlet sashes. Brass bands march through the narrow streets round the twin-spired English-looking cathedral, built when Gascony was a contented fief of the Plantagenets. Young heifers are let loose, chasing, rather than being chased by, the crowd. Brawny young men tussle with the cows — perhaps the origin of their taste for rugby. There’s a darker side: young women are warned not to go alone.

A late dinner under the stars on a cool hilltop near Pau, with nothing between us and cool breezes from Biscay. Our châtelain is John Ranelagh, an Irish Brit who works in Norway and lives a large part of the year here in Gascony. Other guests include an American designer, a Belgian poet (who swapped his family castle in Flanders for another a few miles from here), the artist Michael Baverstock, busily preparing for a show in London, a dashing Kurdish physiotherapist, and the historian Norman Stone, visiting from Budapest. A fair amount of the local Madiran is drunk, and conversation flutters round poetry, words, folklore, history and films; a number of senior academics are tossed and gored (my lips are sealed). We finish at one in the morning, gazing over the wide valley, now velvety dark. And bliss: no one mentions Brexit.

Norman Stone takes us all to lunch to celebrate the completion of his new history of Hungary. We find a little restaurant in the foothills of the Pyrenees, which is full of French families — a good sign. Isabelle and I are going camping higher up in the mountains in a few weeks. Last year foxes stole our food supplies as we slept, including precious tea bags. This time we’ll hang everything in trees. After lunch, John Ranelagh and I count the names on the war memorial: 40 dead, from a tiny village. How much of modern France this explains.

Comments