In April 1945, the Japanese battleship Yamato — the largest and heaviest in history — embarked upon a suicide mission. The ship sailed to Okinawa, where a huge American assault was taking place. Under extensive enemy fire, it sank, as was expected, to the bottom of the Pacific. With it, it took 2,280 of its crew. Survivors’ accounts exist and continued to be taken until very recently. They describe seamen lost even on board, unable to find their living quarters because of the sheer size of the vessel; arrows painted on decks to indicate the direction of the bow or stern; and the testing days before what the crew knew would be the battleship’s last mission.

Jan Morris, however, does not include the human stories of the Yamato. Rather, in this illustrated essay of sorts, she follows the ship’s journey from a distance. She has us watch with her, from somewhere above the ship — perhaps like gods — as it sits in wait off the Mitajiri shore, and from ‘across the darkening water’ as it prepares to set out on its final journey. Rarely does Morris venture on board; while she speculates about the tiny details of the ship and conjures a sense of something that can only be described as its character, she does not linger on the moods or emotions of the crew. The book, however, is no less human for it, since Morris’s tremendous skill is in breathing life into — and making it possible to empathise with — the inanimate: buildings, cities, ports and, this time, a ship.

The Yamato, built at Kure, on the Inner Sea of Japan, at the end of the 1930s, was a heavy, solid, angular and ultimately brutal machine, weighing 65,000 tons, and measuring, in length, 263 metres. It was armed with nine 45 Caliber Type 94 naval guns, six 155-millimetre guns, 24 127-millimetre guns and 162 25-millimetre anti-aircraft guns. It was the most powerful warship ever built — ‘the ultimate battleship’ Morris writes, charmingly (and briefly) shedding her usual elegance. A similarly laid-out Japanese ship shows weapons on vast mounts dwarfing the crew, who are gathered for a group photograph.

Yet, for all of its bravado, the Yamato was not simply a brutal thing, but a beautiful one, as described by Morris. It is a beast, alive and with a destiny: a whale — ancient in its design and purpose — on a mission to beach itself; a ‘tiger on a leash’ while it waits to set sail; and, then, a ‘tiger, unleashed’ when under attack, ‘tormented by insufferable insects in hopeless conflict’. Its end is not a sinking, but a suicide. At this book’s close, when Morris writes of the 1985 discovery of the Yamato’s wreck at the bottom of the Pacific, we imagine, instead of corroded metal, eroded bones — such is the power of the imagery.

The Yamato is a symbol. We begin in Morris’s own study where, on her desk, are models of the English Prince of Wales, the German Bismarck and the Yamato — together, ‘the last word in battleships’. ‘They emblemise for me,’ Morris writes, ‘the extinction of the imperialist ideology, the right of one community to lord over another, a notion which the battleship was a prime executor of.’ But the Yamato, especially, and its sinking — which took place so close to the end of the war — had significance all over the world, not only in Japan. Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, the official historian of the US Navy, wrote that it had ‘a sentimental interest for all sailors — when she went down, five centuries of naval warfare ended.’

That the Yamato was Japanese is incidental to this book. Morris is interested not in the cultural idiosyncrasies of the Japanese or of their weapons, but in the global nature of both. The Japanese are consequently not exoticised or dehumanised (which they often are and have been), or made to seem different to any other fighting force at any other place or time. They are, simply, people under orders, as people have been for millennia.

Morris makes universal (or, at least, more familiar to the West, specifically) the Japanese experience of war — while barely discussing it directly — by telling the story of the Yamato through various paintings (‘Washington crossing the Delaware’ by Emanuel Leutze; ‘Guernica’ by Picasso), and through pieces of classical music (Chopin, ‘with his streaks of something dark among the ecstasies’ accompanies the Yamato while it waits by the Japanese shore; Sibelius, Wagner, Mahler, as it approaches its destination in the night). This is a book that does not see enemies, allies, victors or losers. Rather, the Americans and Japanese ‘contribute’ to a ‘frenzy’; they do not strike each other but are themselves struck by ‘Chaos’.

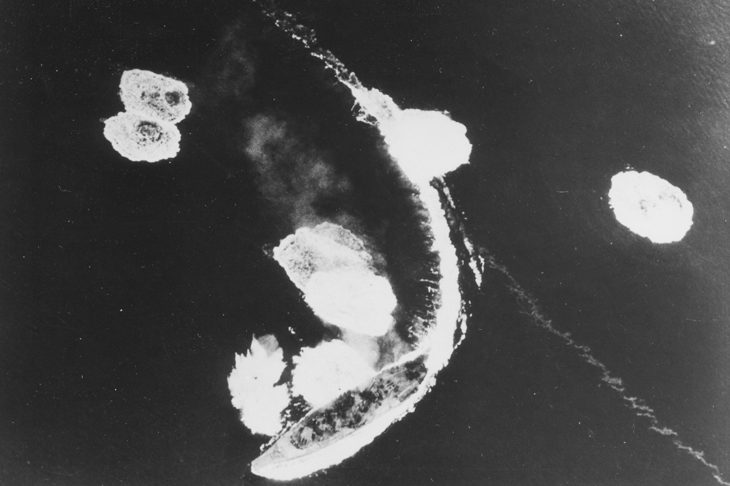

There is a photograph that encapsulates perfectly Morris’s immense powers of description and evocation. In a birds’-eye- view shot of the Yamato evading enemy fire, the ship lifts the surface of the sea into one, curving, white crest, as a whale might. Were we not to know the subject, we might suspect that it was a majestic, living, breathing animal, putting on a show for the people flying over it.

In this book, which is as romantic as it is informative, written as a poet might write about his or her muse, Morris gives the pronoun afforded to all sea-vessels, ‘she’, new weight and meaning.

Comments