The inimitably pukka voice of Jacob Rees-Mogg echoed through Radio 4 on Thursday morning. He was not, though, talking about nappies, nannies or even Brexit; his topic instead was death masks and specifically that made of his father William, the newspaper editor and vice-chairman of the BBC, who died in 2012. Not long after Rees-Mogg had passed from this life, his facial features were immortalised in wax and silicon rubber by Nick Reynolds, godson of Ronnie Biggs and son of Bruce Reynolds (whose names you may recall from the great train robbery of August 1963).

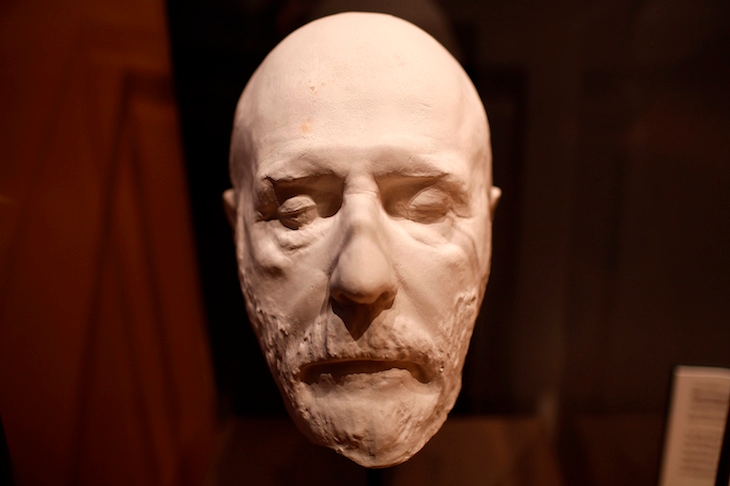

In Death Masks: The Undying Face (produced by Helen Lee), Reynolds talked us through the whole process, from the initial making of an impression of Rees-Mogg’s face with alginate (that horrible pink stuff which dentists use to model your mouth) to layering with bandage strips and plaster of Paris to make the negative. From these basic materials emerges a 3-D image, something solid and tangible, a way of cheating death, of creating a form of immortality. ‘All it needed was a pair of glasses and there was my father staring out,’ said Jacob.

‘Have you ever spoken to it?’ asked Reynolds.

‘No,’ Jacob replied.

‘Has your mother?’

‘No… It’s not my father,’ Jacob insisted. ‘It’s a representation… It’s comforting, though, because it’s evident that he was at peace.’

Rees-Mogg senior is in the company of Ronnie Biggs and Peter O’Toole, both of whom have been ‘immortalised’ by Reynolds, along with the film director Ken Russell and Reynolds’s father. ‘It allows me to talk to my Dad,’ says Reynolds, whose home is filled with death masks he has collected, ‘even though I don’t believe in the afterlife.’

He became interested in death masks after seeing Oliver Cromwell’s at Warwick Castle when he was a child. ‘There’s something magical and mystical about them,’ he says. ‘You capture that person as they would have looked at the moment of death, as if they are sleeping.’

The art critic Rachel Campbell-Johnston asked Reynolds to make one of her partner, Sebastian Horsley, who died suddenly of an overdose, unprepared, without warning. For her, the mask proved ‘a stepping-stone… a link between his animate being and the inert corpse’. It was as if, she said, the mask was an interface, ‘a pair of doors that led me away from him’.

It is hard to imagine either Nadia Comaneci or Simone Biles sitting still for long enough to have their image captured by an artist. In 1976 the gymnast Comaneci stunned the world with her perfect 10 performance on the uneven bars at the Montreal Olympics. No one expected anyone to achieve such perfection so the scoreboard recorded her mark as 1.000, unable to clock up 10 out of 10. Check it out on YouTube, urged Kim Chakanetsa on The Conversation, the World Service programme (produced by Sarah Crawley) in which two women from the same specialist field of endeavour are invited to share their experiences under Chakanetsa’s expert guidance.

If you look again at Comaneci’s gravity-defying catapults and tumbling, leaping, turning and twisting, without ever looking down or having to check her balance, what is so striking is how young she looks, how slender (where did she find the strength to hurl her body about with such apparent ease?), and her absolute joy in every slick, perfectly poised movement.

‘What is happening when you compete?’ asked Chakanetsa. ‘How do you focus? Can you hear the crowd?’

‘I can remember exactly what music was playing,’ said Comaneci. ‘Even though I had to think about every detail I was doing on the beam. That minute and 10 seconds is so long.’

She was in conversation with Biles, who stunned the crowds in Rio de Janeiro last year, winning five medals, four of them gold (her fans told her how disappointed they were that she did not make the full five), as part of the US gymnastics team. Both of them recalled how competitive they were right from the start. Aged about six, Biles was discovered while bouncing on the trampoline at a daycare field trip in Texas, Comaneci sent to the gym by her parents, who were fed up with her breaking the furniture as she somersaulted round their living room in Romania.

If someone said, ‘I bet you could not do that, I wanted to prove them wrong,’ said Comaneci. ‘I was the same kind,’ Biles replied without blinking.

By strange coincidence they have shared the same coach, Biles coming under the tutelage of Marta Karolyi, who was the national coach of Romania until she defected to the US with her husband Bela in 1981 (as did Comaneci in 1989).

Were her methods brutal? asked Chakanetsa.

‘I always did more than they asked me to,’ Comaneci replied.

Simone recalled how Marta used to tell us, ‘If I come and wake you guys up at midnight and you can’t land a beam routine, that’s not good.’

She didn’t see it as unnecessarily harsh; just a way of ensuring they were tough enough to deal with anything that might go wrong on the day. ‘That’s the mentality, you have to think… If you’re really tired, do one more routine.’

Comments