From ‘The Sacrament’, The Spectator, 25 December 1915: We were fairly fagged out, all of us, after a heavy day of it. One by one we scraped the thick, clinging mud off our boots as best we could and took our places at the mess-table. It was a door resting on biscuit-boxes, but we ate what lay on it ready for us as thankfully as if it had been polished mahogany covered with the whitest damask cloth. It was frightfully draughty, and through a shell-hole in one wall came the fitful, silent gleams of the Verey lights as they rose and fell over the trenches. There was an extraordinary silence, broken by nothing louder than the crack of a rifle now and then and the fitful noises of the wind. The guns had stopped their barking and roaring after 50 hours of ceaseless shelling.

The orderly had got a fire going and was clearing away our plates and things when a step upon the stairs turned my eyes to the door. It opened, and an officer came in. We all stood up; I don’t know why, and he held out his hand and told us to carry on. The officer took a box that was in the corner by the fire, and drawing it out, sat down upon it.

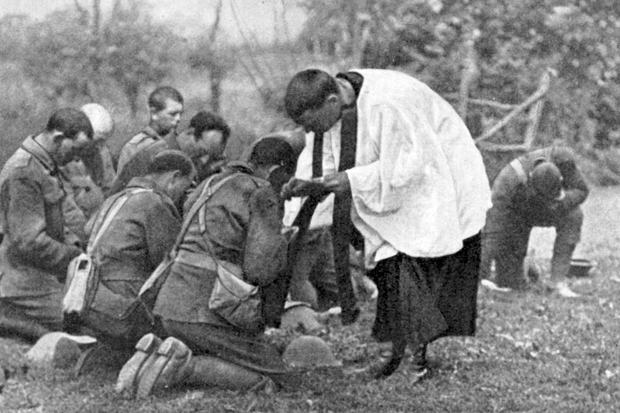

He stopped and asked me for the bread. I passed it to him on the plate, and, feeling ashamed that I hadn’t thought of it before, asked him if he were hungry, adding: ‘It’s been so thoughtless.’ He checked me with a glance. Looking round on us all, he said: ‘I want you all to drink a little to cheer you up. After all, where is The Faith today if it’s not to be found among you? Come, let us all take a little bread together, and remember the day of agony when the Soldier Son died. Try to remember that He of Galilee was none other than the Lord of Hosts, the Lord strong and mighty in battle. Think upon the coming day when He shall come in power; when the graves that sprinkle all these plains shall open and give up their ennobled and glorified dead; when the corrupt matter that made the shell of man shall at the great Call be made eternal and incorruptible. And let us be for ever done with the fictions and fallacies of the blind leaders of the blind. Come,’—and he took the bread, and in his strong but scarred hands broke it, passing it to each one of us. He got up himself to do it. Then he poured out the wine into a tumbler, and we took it one from the other and drank it silently. ‘No need,’ he said as he took the cup from the Major, ‘for solemn feelings and such like, is there? The thing is to go on to the end, however bitter it may be.’

Comments