The first mermaid we meet in this intriguing, gorgeously produced book is spray-painted in scarlet on a wall in Madrid, holding a heart not a mirror. Not your average mermaid, then; but as the folklorist and playwright Sophia Kingshill delves further into their complex cultural history, it becomes clear there’s no such thing. Mermaids can be gorgeous but deadly, like the ones in Pirates of the Caribbean who lure sailors into the sea, then bare their horrible fangs and move in for the kill. They can be vulnerable, like Ariel in Disney’s joyous The Little Mermaid. They can be harbingers of storms, or symbols of female inconstancy.‘It’s always a risk to meet a mermaid,’ writes Kingshill. The Folkestone politician who ditches career and fiancée for a mermaid in H.G. Wells’s novella The Sea Lady wades into the waves and, writes Kingshill drily, ‘is tenderly drowned by her’.

This motif is reversed in West African stories about mermaids who marry men and magically protect them for the rest of their lives. Henrik Ibsen — not usually a fan of a happy ending — does allow his mermaid-like heroine in The Lady from the Sea to find a way to stop floundering on the dry land of her marriage. And, of course, the 1980s classic Splash! ends with sparkly-tailed Daryl Hannah taking Tom Hanks to an underwater paradise — though it’s clear that if he comes with her, he’ll never be able to go back to land.

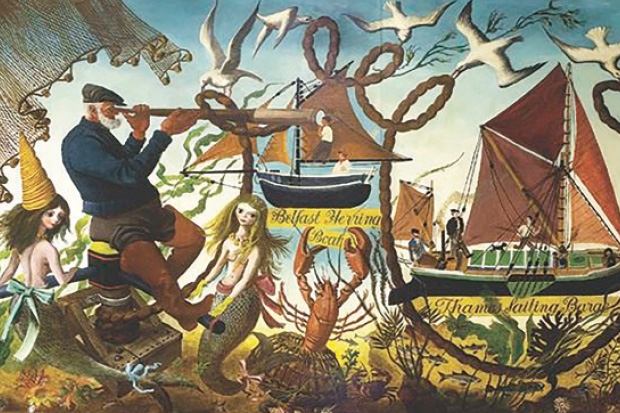

Kingshill is very interesting on the ugly, shrivelled remains of creatures that once appeared at freakshows: monkey corpses hacked up and sewn onto chopped-off salmon tails. Some people really do want mermaids to exist; one of the most bizarre and beautiful images reproduced here (it’s really worth it for the pictures alone) is a woodcut from the 15th-century Nuremburg Bible which shows mermaids swimming around Noah’s Ark. Theologians apparently decided mermaids should have been killed by the Flood because they were anomalous, and therefore clearly sinful; but then decided that because they were aquatic, when the seas overwhelmed the land, they must have carried on as normal.

Selkies appear in this curious book, as do sirens and the half-woman, half-serpent Melusine. Sometimes this is refreshingly ecumenical, and sometimes just confusing. I was also not entirely convinced by Kingshill’s reading of Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’; she focuses almost entirely on how the Little Mermaid longs for a soul, but this comes late in the story, after she has spent years obsessing about the world above the waves, and has fallen head over tail for the handsome prince and saved his life. It’s only then that she starts thinking she might quite like a soul. This part of the story feels bolted-on. I’d always hoped she might leave him, go back to the sea and find love with a nice merman, but mermen have never really captured the imagination the same way. Merfolk (merpeople?) are almost always female, sexualised and described in relation to men, and often also by men.

So can mermaids be meaningful to women too? Kingshill wonders if the mermaid’s props of mirror and comb are as retro-sexist as they seem or if, maybe, the mirror is a symbol of the moon while the comb is a plectrum. I would have liked to know more about how feminists are reclaiming mermaids, more provocations like the ones Kingshill ends with, quoting the anonymous painter of the Madrid mermaid, who scrawled feminist slogans around the sinuous scales. ‘Down with patriarchy!’ ‘Don’t give up on your life, take centre stage!’

Comments