Polar explorers are often cast as mavericks, and this is hardly surprising. The profession requires a disdain for pseudo-orthodoxies and, besides, the urge to dwell on a frozen ocean or forbidding glacier is maverick in itself. In the so-called Heroic Age (the late 19th and early 20th centuries) both Poles remained ‘unconquered’ and the margin between glory and opprobrium was slender. Frederick Cook and Robert Peary claimed that they reached the North Pole in 1908 and 1909 respectively. Their accounts were later discredited. When Roald Amundsen beat Captain Robert Scott to the South Pole in 1911, he was accused (unfairly) of concealing his plans and was summarily shunned by the British establishment. Scott meanwhile forced his expedition on, but in doing so condemned it to disaster. Fending off his critics like an irascible eagle, Amundsen went north again and again, by boat, airship and plane, until, in 1928, he vanished into the ice.

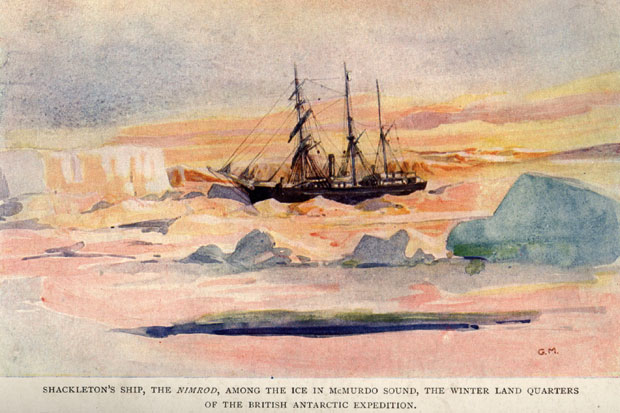

Ernest Shackleton has traditionally been commended for restraint and for sparing the lives of his men. In 1901, Shackleton had served as third officer on Scott’s Discovery expedition, but he fell ill and was shipped home early. This was fairly ignominious; so in 1907 Shackleton led the Nimrod expedition south, hoping to redeem himself. With the Pole 97 geographical miles away, he made the decision to turn back and survive. Later, Shackleton famously escaped from impossible carnage when his ship Endurance was crushed in the Weddell Sea, miles from habitable land.

Michael Smith describes such trials in the ferocious and beguiling detail favoured by polar historians. Smith has previously published works on Irish explorer Tom Crean, Irish exploration in general, Captain ‘Titus’ Oates, and an introduction to Shackleton aimed at children, Shackleton: The Boss. His new biography is clearly aimed at adults; he is more loquacious on Shackleton’s financial woes and extramarital affairs, for example. He muses on Shackleton’s mercurial personality and the strange predilections that compel a man, in defiance of general advice, and irate doctors, to go south. The major biography of Shackleton has been that of Roland Huntford, published in 1985. Smith suggests that it is time for a new one: ‘Much has changed in the three decades since Huntford’s Shackleton, just as the Heroic Age is viewed differently today than it was 30 years ago.’ However, this shift is indebted to Huntford, whose polemical scholarship in the 1970s and 1980s demolished the reputation of Scott and salvaged Shackleton from relative obscurity.

Smith proposes to ‘untangle the myths from the reality’ of Shackleton’s life. He argues that there were two different Shackletons: ‘the charismatic, ambitious, buccaneering Edwardian explorer with a love for poetry, who touched greatness, combating unimaginable hardship and depths of adversity in the most unwelcoming region of the world.’ And there was also ‘the complex, flawed, restless, impatient and hopelessly unproductive character on dry land, who struggled to come to terms with the civilising forces of day-to day routine and domestic responsibilities.’

Shackleton was ‘a one-off, a unique and compelling character who raced through life, rarely glancing sideways and never looking back.’ Smith’s research is detailed and meticulous. He writes in sparsely punctuated, elongated sentences:

Dawn was minutes away on the remote island of South Georgia and the emerging daylight was slowly illuminating the magnificent natural amphitheatre of snow-capped mountains and grassy slopes surrounding the grubby, foul-smelling whaling station at Grytviken.

Yet, when Smith tames his clauses, this is a fascinating book. The story of Shackleton’s 1914 Endurance expedition is well told. Shackleton hoped to traverse the Antarctic continent, but his ship was crushed by sea ice before he even landed. He conveyed his men through hazardous waters in three small, open boats. They landed on Elephant Island, in the Southern Ocean, where most of the party remained, while Shackleton and four others continued by boat to South Georgia. There they made a truly insane crossing of the mountainous interior, and arrived in May 1916 at a whaling station, greeted by startled Norwegians. They emerged into a ruined world, as Smith explains:

Like travellers from a different time, Shackleton, Crean and Worsley were among the few people in the civilised world who knew nothing about the horrific slaughter on the Western Front.

It is a classic story, and Smith tells it with passion and commitment. His Shackleton is billed at the start as a split personality— chaotic in private, disarming in public — and at times, of course, he is neither. The portrait absorbs inconsistencies and anomalies, and becomes more interesting.

Smith’s biography does not replace Huntford’s; the emphases are inevitably different. Besides, a biography is simply one person’s version of reality, and can never be objectively definitive. Of mavericks and heroes there is much to be said.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17 Tel: 08430 600033. Joanna Kavenna, is the author of The Ice Museum, an account of her journeys through Norway, Iceland, the Baltic and Greenland.

Comments