This summer, I returned to Haiti for the first time in ten years. I was itching to see how the Caribbean republic had changed after the terrible earthquake of 12 January 2010. This time, I would not be travelling by jitney, lorry or fishing boat, but in taxis and air-conditioned tourist coaches. Port-au-Prince, the capital, was as exhilarating and exhausting as I remembered it. The streets, thronged with pack animals and porters were a human ant heap. The smells I knew so well from earlier visits — sewage, burning rubbish — hit me forcefully and it was as though I had never been away.

I made a bee-line for the Hotel Oloffson, a magnificent gingerbread mansion made famous by Graham Greene in his Haitian novel The Comedians. Illuminated at night, the hotel was a folly of spires and fretwork. Hurricane lamps flickered yellow, showing white rattan furniture. I had not seen the Haitian-American owner, Richard Morse, since I proposed to my wife here in 1990 (I went down on two knees to Laura after a burst of machine-gun fire startled me). ‘Ian, it’s been too long,’ said Richard, laconic as ever. Not only had he kept the Oloffson open all these years, but he fronts a world-class Vodou rock band, RAM. The band played so well that night that I thought I would levitate out of my seat. Past guests to the hotel have included Nöel Coward, John Gielgud, Marlon Brando and Mick Jagger (who wrote ‘Emotional Rescue’ there); laughably a room had been named after my book on Haiti, Bonjour Blanc.

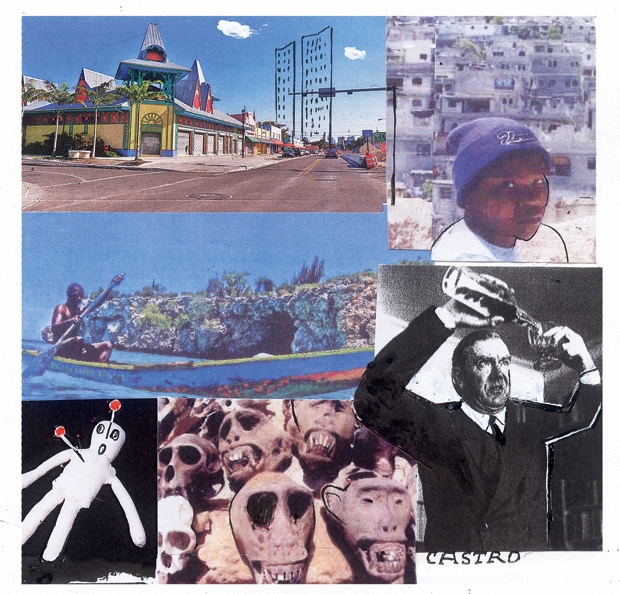

Port-au-Prince was still visibly damaged from the 7.0-magnitude earthquake. The death toll is uncertain but the official Haitian tally is 316,000. It remains one of the worst natural disasters in Caribbean history. The convulsions lasted 35 seconds but were enough to destroy the National Palace; the Episcopal Cathedral with its magnificent, Vodou-inspired murals by Wilson Bigaud and other Haitian artists, the Palais de Justice and the Palais des Ministères were all razed. A more graphic image of municipal chaos is hard to imagine: the heart of Haiti’s national and civic life had gone. Down by the Iron Market, the Grand Rue and Rue Pavée showed extensive damage; the old Syrian-owned warehouses collapsed in the aftershocks that radiated from the epicentre ten miles away in the city of Leogane. In 2012 the Hollywood movie star Sean Penn, who runs a charity out of Haiti, recruited a demolition team and carted off what remained of the National Palace. The building was a painful reminder of the earthquake but many Haitians felt aggrieved that a white foreigner should have taken away their symbol of sovereignty.

Everywhere, I was struck by the fever of rebuilding and reconstruction. At the airport, brightly coloured adverts for Haitian rum and beer adorned the walls; Haitian raboday hip-hop music blared joyously from a speaker box somewhere. New Hilton and Marriott hotels are due to open soon in Port-au-Prince; change is coming fast. Some money may even ‘trickle down’ from the Hilton to the (truly disgusting) seafront slums. The transformation of Haiti into a cruise-ship destination has already started.

No visit to Haiti would be complete, I suppose, without a Vodou ceremony. Vodou reflects the rage and ecstasy which threw off the shackles of slavery. On the night of 15 August 1791, a ceremony was held outside Cap-Haïtien which marked the beginning of the African slaves’ revolt against the colonial French. (Haiti, the world’s first black republic, finally gained independence in 1804.) For many Haitians, Vodou is a way to rise above the misery of poverty and the devastation wreaked by hurricanes, mud slides and other natural disasters. When a Haitian is possessed by a loa (spirit) he is taken out of himself and gratefully transformed.

To attend a Vodou ceremony, you follow the rumble of drums into the countryside. This I did on my birthday, 24 June, St John’s Day. In Vodou, St John the Baptist (Sen Jen Batis) is a powerful, rum-drinking divinity who is propitiated with bonbons and bottles of alcohol. At the village of Trou-du-Nord, in the north, the night air was dirty like a smoked ceiling and eerie with barking dogs. Round the parish church of St John, the candles and the swaying, crowded bodies suggested a Mexican Day of the Dead. Crowds stood round the edge of the Vodou temple of woven palm-thatch; they paid me no mind. The mambo (Vodou priestess) was sweating and jiggering her shoulder like an epileptic. The drummers, bashing furiously, looked similarly possessed. A peaceable religion, Vodou is derived from the rites and beliefs brought to Haiti by African slaves in the 1600s. It is as old as Christianity.

On Haiti’s south coast, the old coffee port of Jacmel lost 5,000 inhabitants to the earthquake. The Hotel Manoir Alexandra, where I had stayed in March 1990 during the coup that deposed General Prosper Avril, was a husk of its old self, its rosewood staircase and roomfuls of French antiques destroyed by tremors. In the municipal cemetery I found Aubelin Jolicoeur’s grave. The dandyish Haitian gossip columnist was immortalised as Petit Pierre in The Comedians. Bizarrely, he had been born in the same cemetery — ‘among the spirits’, he liked to joke — when his mother went into premature labour. His death in 2005 at the age of 81 made headline news in Haiti; he was buried in his signature beige-white suit and silver-topped walking cane.

After a week, my time had almost run out, and I felt a mixture of impatience for home and deep regret at leaving. Haiti is one of the most astonishing places on earth — a West Africa in the Caribbean — and I can’t wait to go back.

Comments