Rossini’s La donna del lago, based on Sir Walter Scott’s poem, is a relatively late work in his brief and unbelievably industrious period of operatic composition. It has its passionate admirers — it is the only opera that Maurizio Pollini has conducted and recorded. The Royal Opera was seething with excitement on the first night of the production by John Fulljames, and the roar of acclamation at the end, which had been preceded by many during the performance, showed that the fashionable and expensive audience was well pleased with what it had seen and heard.

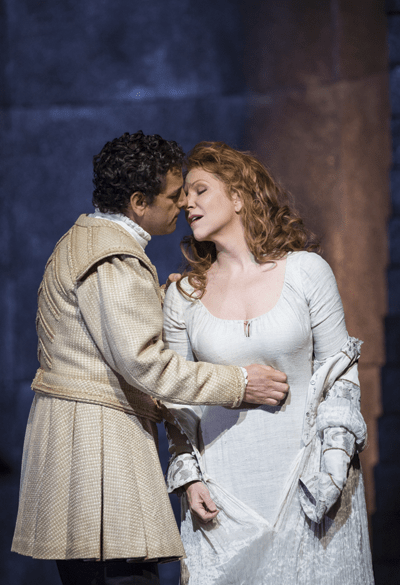

Some of the most spectacular vocal feats that the house has ever witnessed merited that reception: the two chief stars, Joyce DiDonato and Juan Diego Flórez, were on simply staggering form, both of them, if possible, even surpassing the standards that they have set over the past few years. DiDonato is nothing short of miraculous in her capacity to spin endless lines of scarcely audible melody, rounded off with a seemingly endless trill that fades into nothingness, and making it all mean as much as possible, which is very little; while Flórez not only belts out the stratospheric notes that have made his name with all the effortlessness we are used to, but has also acquired a fuller, richer tone, so that he no longer almost yelps, but produces sumptuous sounds that, for lovers of that kind of thing, must provide the experience of a lifetime.

It would be most unfair to confine praise to them, though: the rest of the cast is impressive, and I felt particular admiration for Daniela Barcellona, in the kilt role of Malcom, Elena’s (that’s the Lady) true love, who has not only to appear dressed in the most unflattering way imaginable, but also to sing music almost as strenuous as that of the two leads; and perhaps even more for the young American tenor Michael Spyres as the Highland chieftain Rodrigo, who wasn’t scheduled to sing on the opening night, and who has vocal duels with the King of Scotland, disguised as Uberto, Flórez’s role and in the same register. It was like watching a series of high-wire acts, lasting over three hours.

The trouble is that any interest the opera possesses belongs firmly in the realm of athletics rather than of art, and even the most ardent fan of gymnastics can surely not want more than three hours of it on the trot. DiDonato is reported in an interview with a colleague as saying, ‘I think we are trying to look at the meaning of nationality and how history is repeatedly rewritten.’ I wonder if that remark resonates with one single spectator of La donna. If that is what we are looking at, surely it would be a good idea to concentrate the mind by getting rid of most of the pyrotechnics — but then nothing would be left. Certainly Fulljames’s production doesn’t suggest anything of the kind. It is archly post-modernist, with Sir Walter sitting on one side of the stage writing the script while Signor Rossini sits over the other composing the music, also doing some cooking, as a celebrated gourmet.

The curtain rises on a promising romantic landscape backdrop, but the chorus appears wearing G & S-style helmets and scanning the horizon in unison, so that one fears an evening of parody. Elena is wheeled forward in a glass cage, and near the end of the opera seems to enter a flower-lined coffin, though this is an upbeat piece so she and Malcom are reunited. The chorus is mainly dressed in black formal wear. This is a piece for canary fanciers, a breed of which, to judge from its reception, there is no shortage.

The previous evening I had seen at the Royal Academy of Music two operas that give the genre its dignity. Unfortunately Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas was unkindly produced but, worse, unsympathetically conducted by Iain Ledingham in an ‘authentic’ style that might easily have been mistaken for incompetence. Surtitles were badly needed, though Sarah Shorter’s Dido was lucid; but Sónia Grané’s Belinda might as well have been singing in her native Portuguese.

After the interval came a masterly account of Peter Maxwell Davies’s The Lighthouse, his finest opera after the great but neglected Taverner. Davies wrote the text of The Lighthouse himself, and crammed far too much into its 75 minutes; nonetheless it is a gripping, effective piece, and received an exemplary account, under Lionel Friend, surely the most underrated of conductors. The orchestra, a different set of players from Dido, was magnificent, and so were the performances of the three characters, trapped in their lighthouse and having different encounters with the Beast, which for us in the audience was figured by blinding lights. Iain Milne as Sandy, the would-be peacekeeper, Samuel Queen as Blazes, the bawdy sceptic, and Andri Björn Róbertsson as Arthur, the insufferable fundamentalist, all gave performances that would have graced any production in the world. The music, a characteristic product of Davies’s middle years, mixes passionate lyricism and raucous nihilism to powerful effect, and once again I wish that the RAM’s operatic efforts could be preserved on film.

Comments